by MALFRED GERIG

Global hegemony in the interstate system refers to the capacity of a leading state to exercise leadership and governance within the anarchy of supposedly sovereign states, which are constantly seeking wealth, power, prestige or security. Giovanni Arrighi aptly noted that global hegemony is not the same as pure and simple domination, as the hegemonic state must be capable of steering the interstate system toward a kind of general interest, at least that of the owning classes and those in power.1 The capitalist world-economy is not a global empire; therefore, becoming its hegemonic power has always required a certain mix of coercion and consent. Coercion alone is not enough to dominate the world. The United States’ historical global hegemony over the modern world-system is no exception. However, given the rugged path embarked upon by the Trump 2.0 administration, it seems increasingly evident that US hegemonic power, in its crisis-dispute phase, is seeking to counter its loss of relative power in the field of consensus by doubling down on coercion, “mafia-style blackmail”, exploitative domination and the pursuit of submission.

The question then arises: what has changed in the US’s Grand Strategy under Trumpism, particularly during his second administration? The purpose of this essay is to explore this question in three parts. Part I will delve into homegrown traditions that shape the matrix of US foreign policy, to argue that Trumpism amalgamates reactionary forces within the interstate system. A forthcoming Part II will address the political economy of Trumpian neomercantilism and, concurrently, explore the hypothesis of a McCarthyist foreign policy toward Latin America. Finally, Part III will examine new imperialism, exploitative domination, and empire through submission as responses to the current hegemonic conflict in the capitalist world-economy, in light of Trump’s foreign policy toward Latin America during his second administration.

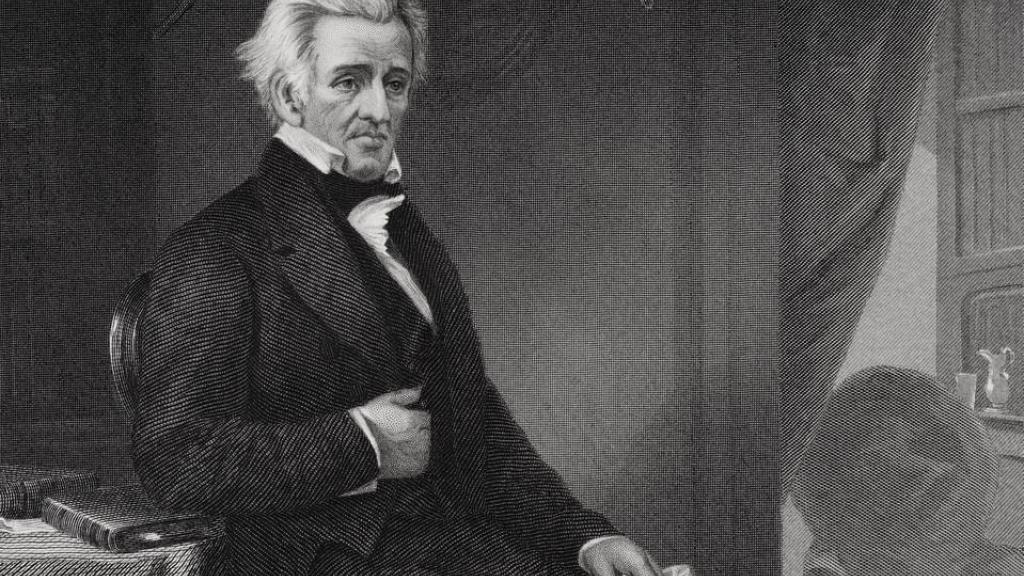

1. Trump 2.0: A Hamiltonian Jacksonianism?

How should we characterise Trump’s second term administration’s foreign policy? To answer this question, we need to turn, prima facie, to the typology developed by Walter Russell Mead in Special Providence. There, the author sets out to strip US foreign policy of the interpretive framework of European realpolitik, most associated with Henry Kissinger and Zbigniew Brzezinski, in favour of looking at more homegrown traditions.2 To Kissinger’s typology, composed of Wilsonian idealism and Rooseveltian realism, Mead counterposes four types. In the words of Perry Anderson, Mead believes:

the policies determining these ends were the product of a unique democratic synthesis: Hamiltonian pursuit of commercial advantage for American enterprise abroad; Wilsonian duty to extend the values of liberty across the world; Jeffersonian concern to preserve the virtues of the republic from foreign temptations; and Jacksonian valour in any challenge to the honour or security of the country.3

Characterising the first Trump administration (2017–21), Mead wrote in early 2017 that Trumpism represented a Jacksonian rebellion against the standard pillars of US foreign policy since World War II.4 According to Mead, Obama had been the president with the greatest contempt for the Jacksonian legacy, while Trump was its revenant.5 But what is the Jacksonian tradition? And, more importantly, to what extent can we take seriously the capacity of the Jacksonian tradition to shape the second Trump administration’s foreign policy? After reviewing, in comparative terms, the extensive history of the US’s capacity to kill people abroad, Mead writes in Special Providence:

Nevertheless, the American war record should make us think. An observer who thought of American foreign policy only in terms of the commercial realism of the Hamiltonians, the crusading moralism of Wilsonian transcendentalists and the supple pacifism of the principled but slippery Jeffersonians would be at a loss to account for American ruthlessness at war. One might well look at the American military record and ask William Blake’s question in “The Tyger”: “Did he who made the Lamb make thee?”.6

Links for more