by JON ASKONAS

Here lies a beloved friend of social harmony (ca. 1500–2000). It was nice while it lasted.

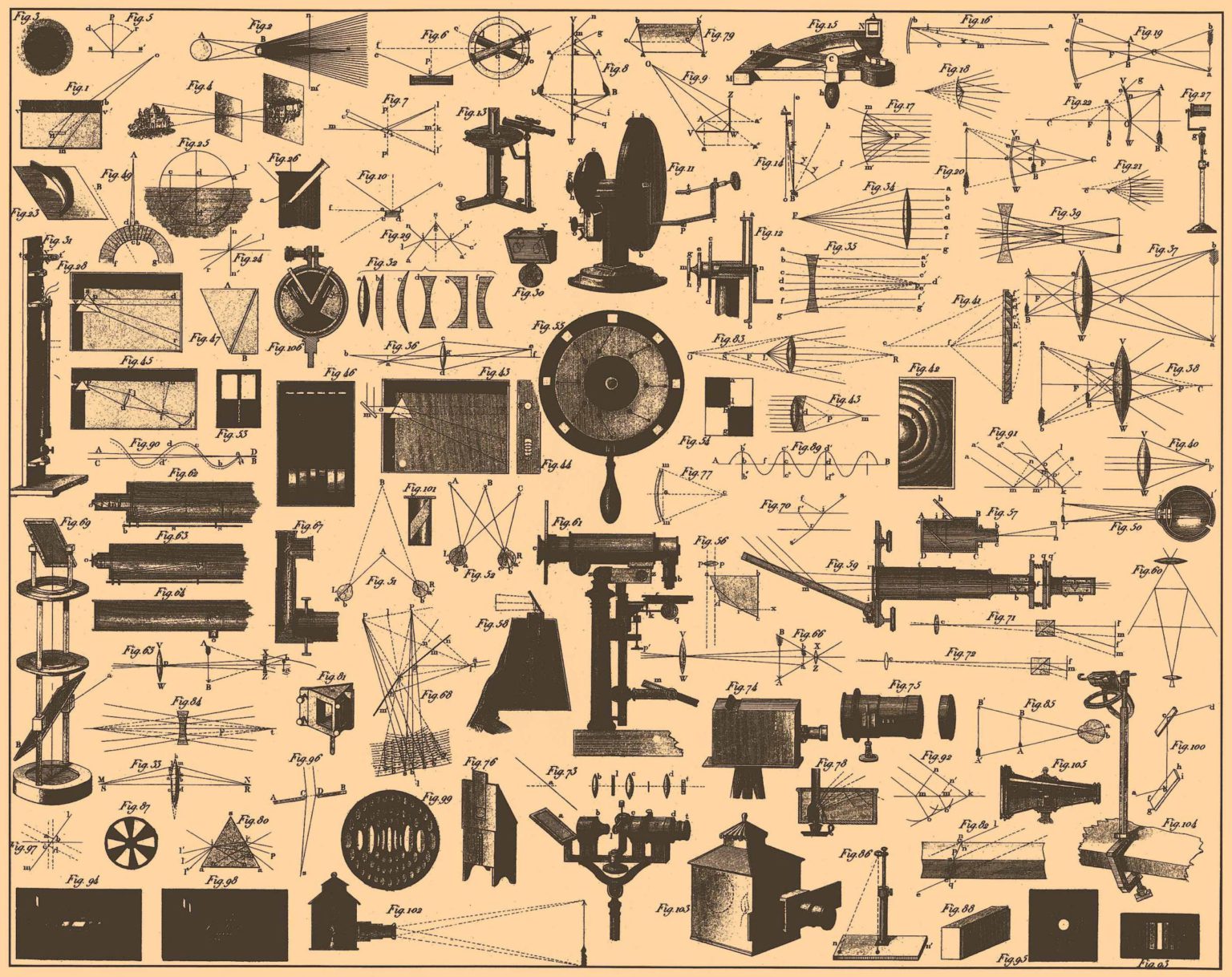

Facts, like telescopes and wigs for gentlemen, were a seventeenth-century invention. — Alasdair MacIntyre

How hot is it outside today? And why did you think of a number as the answer, not something you felt?

A feeling is too subjective, too hard to communicate. But a number is easy to pass on. It seems to stand on its own, apart from any person’s experience. It’s a fact.

Of course, the heat of the day is not the only thing that has slipped from being thought of as an experience to being thought of as a number. When was the last time you reckoned the hour by the height of the sun in the sky? When was the last time you stuck your head out a window to judge the air’s damp? At some point in history, temperature, along with just about everything else, moved from a quality you observe to a quantity you measure. It’s the story of how facts came to be in the modern world.

This may sound odd. Facts are such a familiar part of our mental landscape today that it is difficult to grasp that to the premodern mind they were as alien as a filing cabinet. But the fact is a recent invention. Consider temperature again. For most of human history, temperature was understood as a quality of hotness or coldness inhering in an object — the word itself refers to their mixture. It was not at all obvious that hotness and coldness were the same kind of thing, measurable along a single scale.

The New Atlantis for more