by LIZ FOUKSMAN

Since the 19th century May 1 has been International Worker’s Day, chosen by organised labour to celebrate the contribution of workers around the world. But it’s frequently forgotten that the day actually celebrates a particular achievement of the labour movement: being able to do less work. Not better paid or decent work, but shorter working hours.

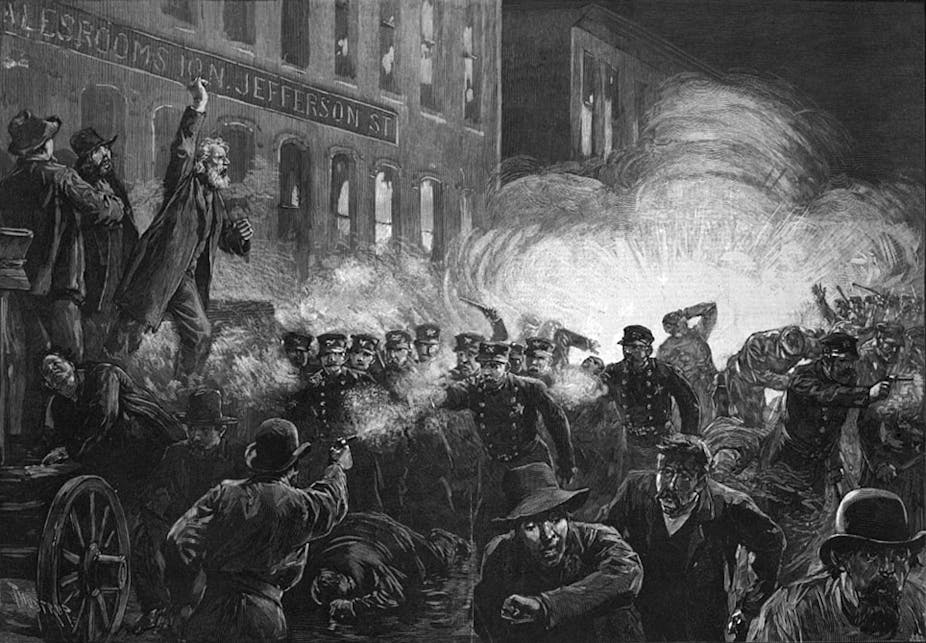

May 1 initially commemorated the 1886 Haymarket affair, where Chicago workers were striking for a radical and dangerous proposal: the eight-hour work day. This idea was so incendiary that the protests turned violent; both police and protesters died in the conflict.

Today more and more people around the world are facing precarity, casualisation, inequality and unemployment. It’s time to pursue a new agenda for a new global labour movement – or rather, to update the old agenda of the 19th century: less working time and more money for all, in the form of shorter work days and a universal basic income.

What happened to the struggle?

An eight-hour work day and weekends off were far from the norm for most full-time workers before the early 20th century. They usually worked 12 to 16 hours a day, six days a week. It took a protracted, often violent organised labour struggle in the face of strenuous opposition to change that.

Forty-hour work weeks were finally legislated around the world less than a century ago. This seemed like just the beginning. The economist John Maynard Keynes predicted in 1930 that thanks to technology, within a century we’d all stop worrying about subsistence. We’d work 15 hours a week, just enough to keep us from getting bored.

Conversation for more