by LAUREEN AKOA WESONGA

Kenyans are passionately split into two constituencies: those that remember the late former president Daniel Arap Moi as vile and reprehensible and those that remember him as a benign Baba. But it is our duty to critique him, to hold him accountable for his wrongs, and to allow the stories he suppressed to be told. This is necessary as it is also cathartic, an exercise that can be the beginning of an exorcism that this country’s troubled soul so desperately needs.

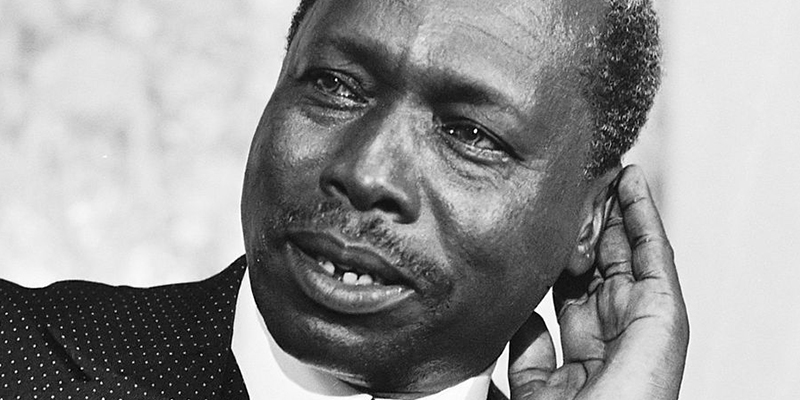

The death of former president Daniel Toroitich Arap Moi has drawn mixed reactions from various quarters. On social media, there are those who are feting his strengths, from his health and discipline in keeping physically fit, to the Maziwa ya Nyayo school feeding programme, to keeping Kenya “an island of peace”. Then there are those who remember him as the man who ruled Kenya with an iron fist, under whose regime there were several hugely controversial and still unresolved murders, most glaringly that of former foreign affairs minister Robert Ouko. Then there are those others who, in cynical Kenyan fashion, are demanding a public holiday because, well, am not sure why, but that’s just the Kenyan condition, in its fearful and wonderful glory. To say the reaction to Moi’s death is a mixed bag is an understatement. That different people have different ideas of his legacy should not be something to be resisted but something to be accepted and celebrated.

I remember as a child in the early 90s sitting with my late dad, an avid historian—and my sisters, watching Moi on television addressing a huge crowd. One of my sisters wondered why people would choose to come out and cheer such an awful politician with such a terrible political record. (For context, I was born and raised in a region that made no bones about its disdain for Moi. Combine that with a household that approached politics with a critical fascination and that conversation wasn’t out of place.) It is my dad’s response that I so clearly remember: “Regardless of what we know or think about him, look at that turn-out, history will judge him as a popular man”.

In a country with a short memory, a terrible grasp of history and a hugely youthful population where more than two-thirds is under 25 years, it may be difficult to recall a time when the level of expression and openness we are currently experiencing was unheard of. That we can say what we think about the late president should be celebrated as a sign of freedom of expression, one that wasn’t available under his regime. Moi is like that elephant in the old poem that several blind men touched and interpreted to be different things. Just like the elephant was a wall, a fan, a tree, etc., Moi was a dictator, a tribalist, a corrupt individual, a political strategist of Machiavellian genius, the man who ruined a country, the tree planter, the gabion builder and, of course, just Baba. Baba who walked with his ivory rungu (with all its phallic symbolism), the emblem of his power and exclusivity. Moi was all these things to different people.

The Elephant for more