by PILAR VILLANUEVA

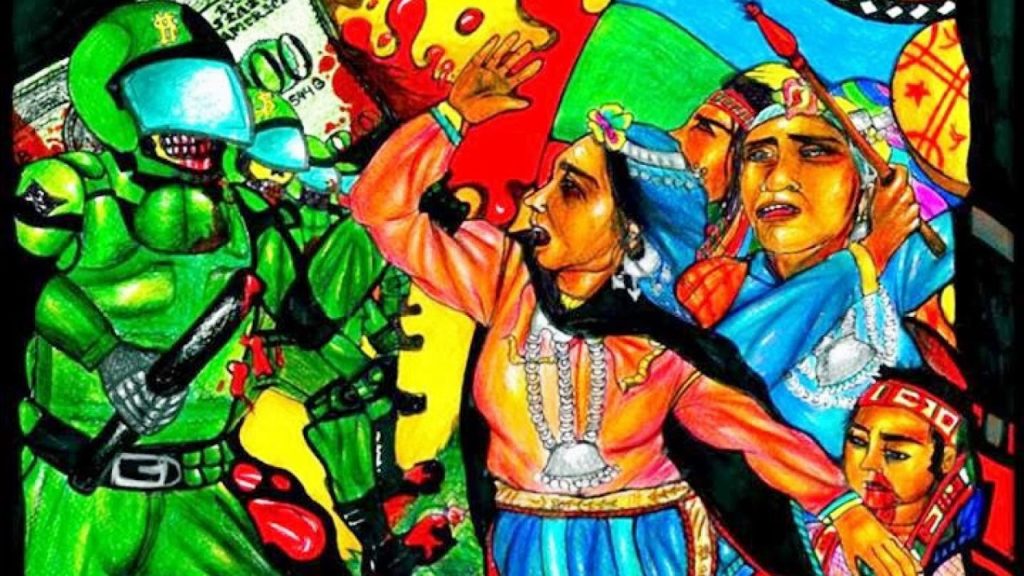

It is no longer accurate to speak of one feminism, encapsulating the experiences of white women in the west and laboring women in the global south, for example. Rather, today, we speak about feminisms, different branches fighting in the cause of women’s freedom, and created by women from the so-called ?third world” – women of color, black women, and indigenous women. These feminisms were brought into being when women from around the world began to critique the limitations of the sort of universal feminism that come from the white bourgeois women in the West to explain our own realities.

Thanks mainly to the legacy of black feminism, plus the work done by social activists in Abya Yala (a decolonial term to refer Latin America and the Caribbean region), for generations we have been building a feminism that describes our needs, goals and political program. We call this decolonial feminism. As we forge decolonial feminism, new archives of women from Abya Yala such as the collection of the late feminist activist and founder of Gender Studies and the Women’s movement in Chile, Julieta Kirkwood, can only lead us to further strengthen this feminist and political project.

Knowing when decolonial feminism started can be at least problematic because, as with many other theoretical concepts, the historical record of women is full of silences. So many women in history have done and said things which were never recorded, because women have historically been restricted from reading and writing, and the men in charge never thought these struggles and ideas were worthy of ink.

A good place to start, however, would be when Sojourner Truth, a free black woman, famously declared ?Ain’t I a Woman?” in a speech for the Ohio Women’s Rights Convention in 1851. This speech and phrase may be one of the first expressions which shows the power relationships dividing ?women.” Sojourner knew that her position and circumstances as a black woman who fought slavery for her freedom and that of her community, was different than that of white women.

Following this idea, other important black feminists and activists such as Angela Davis or bell hooks, developed a more complex understanding of their experiences. Later this would be called intersectionality by another black woman, Kimberlé Williams Crenshaw, an academic. In fact, it was black feminists who first realized the complexity of the oppression in their daily life, which was permeated by broader issues related to race, class, and sexuality.

Just like the concept of intersectionality was taken from black feminist thought, decolonial feminism has a similar construction. We can recognize at least two sources that took part in the emergence of decolonial feminism: 1) the collective political practices and activism forged by people from Abya Yala, along with those from critical feminisms, and 2) decolonial theory built by Latin American thinkers. These feminisms criticized the feminism produced by white feminists.

The kind of feminism being criticized is rooted primarily in the experiences of middle and upper-middle class white women in Europe, Australia, South Africa and the US. It is one that tried to make itself universal, and emerged when many white women were fighting for their right to vote. And yet, many of these founding mothers of feminism had little to say about Apartheid, Jim Crow, and indigenous genocide. It was a feminism that tried to make itself the “feminist common sense” while aiding in the oppression of women everywhere. In other words, it was a “hegemonic feminism” that came from privileges of class, race, gender, sexuality, and geopolitics.

In order to correct this kind of feminism, and replace it with one that captured the various struggles of women everywhere, the Argentinian scholar María Lugones began to use the term ?decolonial feminism.” In a broad sense, she has argued that feminism must fight coloniality, which refers not just to the historical legacies of colonialism, but to the effects of the power relationships in a world scale, where colonialism, capitalism, and western globalization were an inseparable triad in the project of modernity.

In my case, being a woman and feminist in Chile was a completely different experience compared to when I came to work in the US for the first time in 2015. Coming from the South and a working-class family made me realized how far I was from other women who grew up and developed in these middle-class and upper middle-class institutions and country. It made me understand better my own experiences in a wide scale while giving me more strength and clarity for the sort of feminism I wanted to build.

Living in constant fear of going home by yourself at night, knowing that most of us have been sexually abused, not having enough money to access good education or in other cases to fulfill our basic needs, are just some of the struggles we face every day in the South. We face more poverty because our resources have been taken away under the colonial and capitalist order, so these situations happen with more intensity in our countries than in the US, Europe, or Australia.

All these reflections brought me to a feminism which focuses in our own experiences as women and bodies in Latin America, affected by colonialism/coloniality, racialism, the capitalist and neoliberal economy, and contemporary patriarchy that was at the same time the product of ancestral and colonial patriarchies.

It may seem to some that decolonial feminism is just an academic buzzword, but the word itself captures the practice of political projects taking place in the global south. Like me, different feminist organizations, collectives, and people in Abya Yala are now engaging with this political project, practice and thought. For instance, my comrades and I, who previously organized with anarchist-libertarian and anarchist-feminist platforms in Chile, have created our own collective called Quimera to explore and move towards the creation and dissemination of our thought and political project permeated by decolonial feminism.

Toward Freedom for more