by BARRY GREY

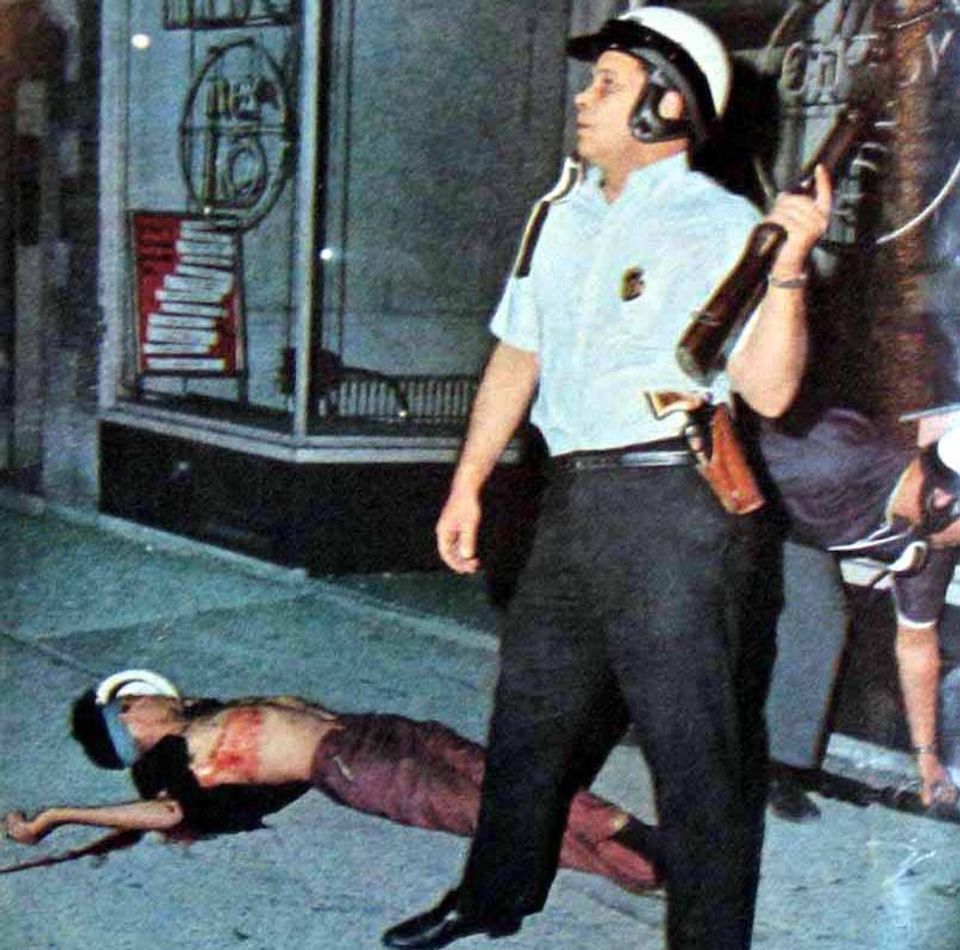

Detroit policeman standing over dead “rioter”

Detroit policeman standing over dead “rioter”

Part three: Liberal promises and capitalist reality in “New Detroit”

This is the third and final part of “Twenty years since the Detroit rebellion,” originally published in 1987. Part one was published on July 21, part two on July 22.

By Thursday, July 27, 1967, the worst of the rioting in the streets of Detroit was over. The revolt of the most oppressed and poverty-stricken sections of the working class had been put down by the occupation force of army troops, National Guardsmen, state and city police.

Parts of the city’s black ghettos were still smoking and entire blocks of houses were in rubble. A thousand families were sleeping on the sidewalk, burnt out of their homes. Thousands of Detroiters remained penned up in jails and makeshift detention centers, under inhuman conditions. Forty-three Detroiters lay dead and 1,189 injured, most of them blacks.

The 9 p.m. to 6 a.m. curfew was to remain in effect until the following Tuesday, the day that the federal troops would be withdrawn from the city streets. But even before the troops were removed, the ruling class, shaken and frightened by the spread of urban rebellion, began a conscious effort to revamp its political machinery for duping the masses with democratic illusions and, when necessary, stamping out their resistance by force.

On July 27 in Washington, President Lyndon Johnson announced the formation of the National Advisory Commission on Civil Disorders, headed by Illinois Governor Otto Kerner. On the same day, in Detroit’s City-County Building, Governor George Romney and Mayor Jerome Cavanagh headed up an extraordinary meeting of 39 people, including virtually every top corporate executive in the city.

Also present were United Auto Workers (UAW) President Walter Reuther; Jack Wood, Detroit & Wayne County Building Trades Council secretary-treasurer; state and local Republican and Democratic officials; and black city officials, churchmen and administrators, including Arthur Johnson, Detroit Public Schools deputy superintendent; and Damon Keith, Michigan Civil Rights co-chairman.

There was even a black nationalist radical, a young man by the name of Norvel Harrington.

The list of corporate chiefs at the meeting reads like a “who’s who” in the ruling circles of Detroit: General Motors President James M. Roche; Henry Ford II; Chrysler Chairman Lynn Townsend; department store magnate Joseph Hudson Jr.; Detroit Edison Chairman Walker Cisler; financier and industrialist Max Fisher; Ralph McElvenny, president of Michigan Consolidated Gas; William Day, president of Michigan Bell Telephone; and department store owner Stanley Winkelman.

New Detroit Committee

This meeting established itself as the New Detroit Committee (NDC), later to become New Detroit Incorporated. Billed as the “new urban coalition,” a meeting of minds of the rich and powerful, the representatives of labor and the black community, it was a high-powered and at the same time desperate maneuver by the capitalist rulers.

The rebellion had proven that they could not continue to defend their property and profits without making changes in the political apparatus. The red-neck police chiefs of the past and virtually all-white political establishment had to be changed. They had to find black middle-class elements whom they could trust to defend their interests. Some of the spoils of exploitation had to be shared with “responsible” blacks, who would help keep down the working class masses.

The police force could no longer maintain law and order as an open and virtually lily white occupation force in the ghettos. More blacks had to be integrated into the force and trained to serve as uniformed gunmen for the ruling class.

World Socialist Web Site for more