by PATRICK IBER

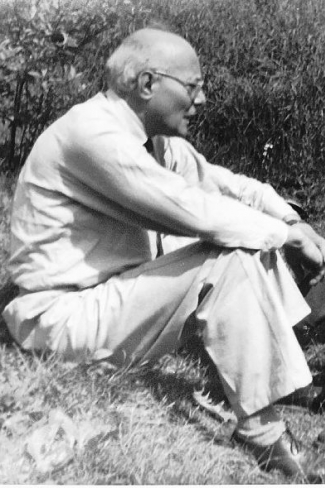

Karl Polanyi PHOTO/Karl Polanyi© Kari Polanyi Levitt

Karl Polanyi PHOTO/Karl Polanyi© Kari Polanyi Levitt

We live in Polanyian times. In his classic The Great Transformation (1944), Karl Polanyi, an economic historian, argued that, contrary to free-market dogma, markets are never natural and are always created by states. “Laissez-faire was planned,” Polanyi wrote, but “planning was not.” The surprising success of Bernie Sanders and Donald Trump in 2016 made Polanyi’s work especially fresh and current. He argued that markets were corrosive to community life, reducing human beings to commodities, and called the spontaneous reactions of people to defend communities from the damage done by unfettered markets the “double movement.”

The global financial crisis increased interest in socialist ideas, as well as right-wing populism. Both can be seen as part of the “double movement.” “Fascism,” asserted Polanyi, “like socialism, was rooted in a market society that refused to function.” Historians of capitalism, such as Sven Beckert, have taken note, observing the Polanyian creation of markets, critical theorists like Nancy Fraser deploy Polanyi’s idea of “fictitious commodities,” and development economists like Dani Rodrik argue that social protection has to be offered to communities exposed to the corrosive winds of globalized capital.

Yet despite the growing relevance of Polanyi’s ideas, until now he has never been the subject of a comprehensive biography, making it difficult to situate his ideas in the historical contexts that produced them. This is especially important because the radical social democracy he espoused has all but vanished from global politics. But the cosmopolitanism of Polanyi’s life posed a real challenge to researchers: Born in 1886, he spent a formative decade in Vienna, then divided working years between England, New England, and Canada. His was, as his biographer, Gareth Dale, argues, a “twentieth-century” life, full of the dislocations of dark years of violence. (He died in 1964.)

Dale, a scholar of politics and history at Brunel University, bases his Karl Polanyi: A Life on the Left on wide research and interviews with Polanyi’s relatives, and the result is informative and intelligent. The biography also suggests Polanyi may be a better prophet for our time than he was an analyst of his own.

Dale narrates Polanyi’s life through a series of internal contradictions. Born into a Jewish family, Polanyi came to identify strongly with Christian morality. He was a supporter of peasants but lived an almost entirely urban life. He has become one of the 20th century’s best-known social democrats but disliked much of the social democracy of his day. He was a humanist — as Dale puts it, “in the sense that he held that anything that violates human dignity should be subjected to theoretical criticism and practical obstruction” — but he frequently defended Stalin’s Russia, and he married a Bolshevik. He is remembered as a warm and generous friend and colleague but took himself to task in a letter to his brother as an “impossible person” who suffered periodic bouts of serious depression.

The Chronicle of Higher Education for more