by BRAD DUNNE

ILLUSTRATION / Carmen Belanger

ILLUSTRATION / Carmen Belanger

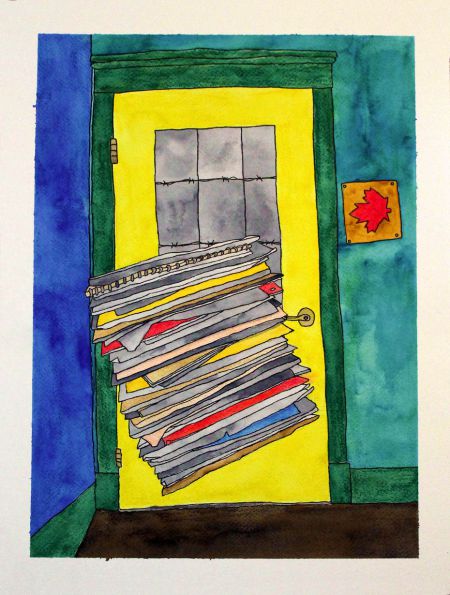

Lack of support forces newcomers out of Newfoundland

When refugee claimants arrive in St. John’s, Newfoundland, Jose Rivera, executive director of the Refugee and Immigration Advisory Council (RIAC), tells them to go to another province. “Don’t go to the airport,” he says, “just grab a bus and go to Halifax or anywhere else you can reach.”

The reason is simple. There is no one in Newfoundland to help claimants through the different levels of bureaucracy. A 2009 study funded by the Harris Centre at Memorial University reveals a troubling lack of information being shared with newcomers. In a survey of 47 immigrants and international students, only 36.2% had received information on how to contact immigration agencies.

“Services are there,” says Rivera, “but you have to get there knowing what you don’t know, so you can ask the question you don’t know how to ask.” He speaks from experience: when he came to Newfoundland with his family as a Colombian refugee in 2002, he was unable to find steady work despite his business background. His organization is a non-profit NGO that assists new Canadians with services such as English language classes, sponsorship contacts, deportation intervention and sanctuary support.

The 2009 study found that less than half of those surveyed had received information on how to access medical services and how to find housing. Only 19% had received information on how to get prior education or credentials assessed and obtain Canadian equivalents for international qualifications.

Legal services for newcomers are also paltry. Only two legal aid staff lawyers in Newfoundland handle approximately 60 to 70 immigration and refugee law cases a year and they do not even work exclusively in immigration and refugee law, running a mixed practice that also includes criminal, family and poverty law.

The single available immigration lawyer in Newfoundland, Meghan Felt with McInnes Cooper, rarely works with refugees, instead mostly working on business immigration and helping residents sponsor family members and spouses.

“The biggest problem is that when people come here, they just don’t know where to go,” says Felt.

The claim process for new refugees can also drag on for several years. “You submit your application, and that gets sent to either Ottawa or the Canadian embassy of your home country, but then there’s no one to talk to you,” explains Felt. “They end up not filling in the right documentation and they get rejected or they have to appeal, and the whole process can drag on for up to five years.”

The Dominion for more