by NYLA ALI KHAN

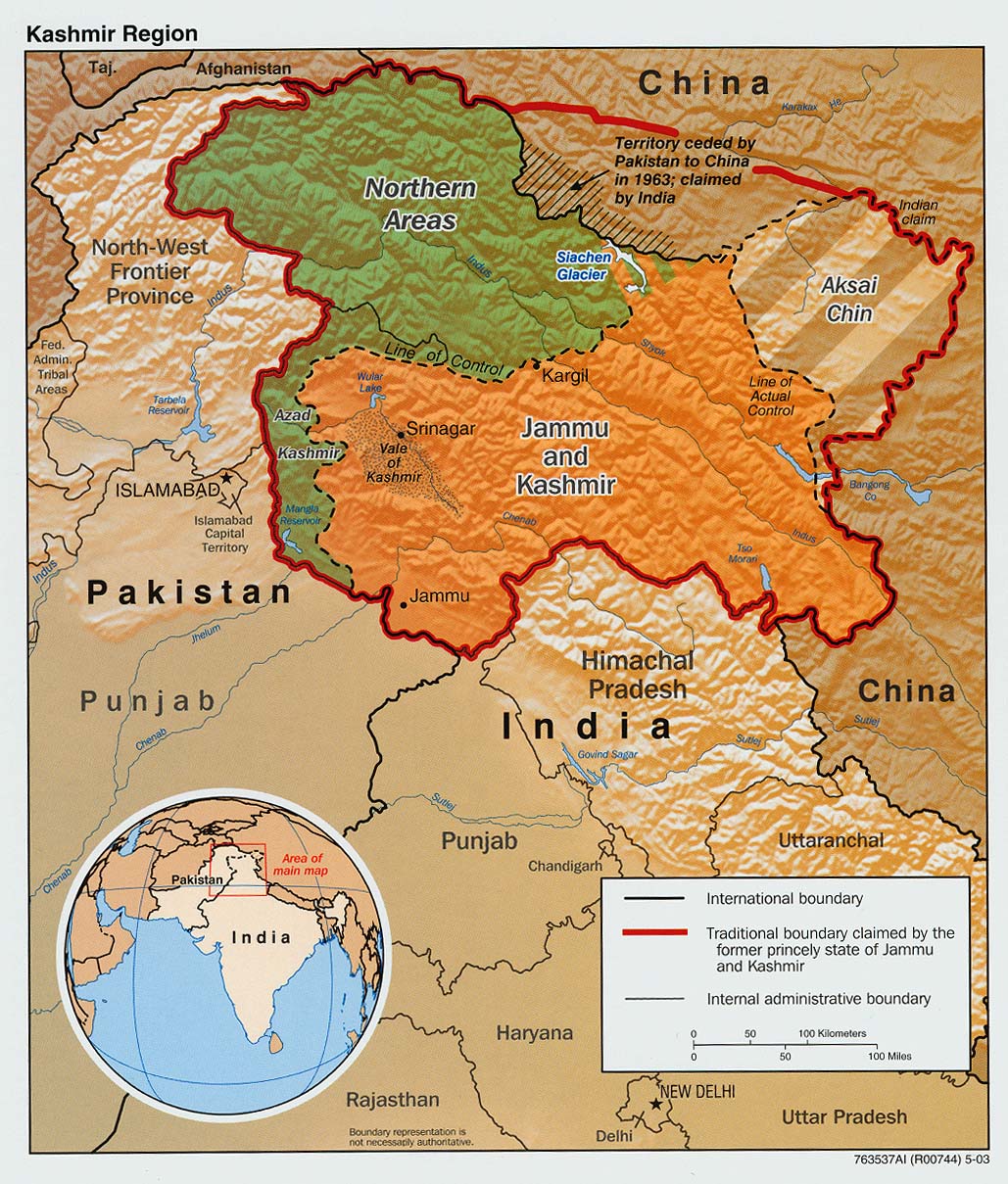

MAP/Library, University of Texas/Google

MAP/Library, University of Texas/Google

To give the reader a holistic picture of that event of great historical and political significance, Sheikh Mohammad Abdullah’s side of the story should, in my opinion, have been given space as well, and the complexity of the situation should have been foregrounded.

Did the government that was installed in the state of Jammu and Kashmir as a result of the August 9th 1953 coup enjoy even an iota of public confidence? Could that government boast of having a representative character? Sheikh Mohammad Abdullah had the indubitable right, as leader of the House and Prime Minister, to face the motion that Bakshi Ghulam Mohammad and G. M. Sadiq brought against him in the Constituent Assembly of J & K. Sheikh Mohammad Abdullah and his colleagues, who had been incarcerated along with him, were prevented from attending the session of the Constituent Assembly in which the Bakshi and Sadiq clique ratified his undemocratic arrest and unlawful imprisonment. Ideally, a vote of the House obtained in such a dubious situation should have no legitimacy. The ruling Bakshi and Sadiq clique brazenly negated the principles that the harbingers of democracy in the state held dear and for which some of them had unhesitatingly laid down their lives. The draconian law of Preventive Detention, which held sway during Bakshi Ghulam Mohammad’s regime, authorized arrests for which warrants were not required, and a detainee could be held without trial for a period of up to five years. The bizarre and harsh law was used unabashedly in 1953 and after, during the period of Abdullah’s incarceration, for coercing opponents to resign or for imprisoning them without a formal charge. It was even deployed for illegally detaining opponents for vocally proclaiming their opposition to the ruling clique on the floor of the House.

During that undulating period, the government headed by Bakshi raised and bolstered a “Civil Army” called “Peace Brigade,” which was patronized by the government so they could flagellate people publicly, plunder in broad daylight, and inflict unaccounted atrocities on those who dared to raise their heads against Bakshi and his cohort. This organization comprised criminals who successfully struck terror into the hearts of the populace. The political enfranchisement of the people, which had been gained after tremendous sacrifices ad hard work, was severely damaged.

In his opening address to the Constituent Assembly of J & K on November 5, 1951, Sheikh Mohammad Abdullah states,

“After centuries, we have reached the labor of our freedom, a freedom which for the first time in history, will enable the people of J & K, whose duly elected representatives are gathered here, to shape the future of their country after wise deliberation, and mould their future organs of government. No person and no power stand between them and the fulfillment of this, their historic task. We are free at least to shape our aspirations as people and to give substance to the ideals which have brought us together here.

“To take our first task, that of constitution making, we shall naturally be guided by the highest principles of the democratic constitutions of the world. We shall base our work on the principles of equality, liberty, and social justice which are an integral feature of all progressive constitutions. The rule of law, as understood in the democratic countries of the world, should be the cornerstone of our political structure. Equality before the law and independence of the judiciary from the influence of the executive are vital to us. The freedom of the individual in the matter of speech, movement, and association should be guaranteed, freedom of press and of opinion would also be features of our constitution.”

If, as the Sard-e-Riyasat, Bakshi Ghulam Mohammad, and G. M. Sadiq claimed, Sheikh Mohammad Abdullah had lost the confidence of his cabinet, the legitimate procedure for those cabinet colleagues would have been to tender their resignations and then make their opinion known to the House by a formal no-confidence motion. This established and recognized procedure of parliamentary democracy was rendered null and void by the happenings of August 9, 1953. Did the State Constitution vest such authority in the Sard-e-Riyasat, the constitutional/ titular Head of State, to arbitrarily dismiss a democratically elected government? Can the arbitrary incarceration and detention of the elected representatives of the electorate of J & K be explained away?

Contrary to the claims of the Bakshi-led government, freedom of expression and speech were unabashedly curbed during his regime. After the mauling of an editor of The Daily Martand, in its editorial of February 3rd, 1956, it clearly condemned the high-handedness of Bakshi’s three year old regime. At the time, Sadiq was the President of the Constituent Assembly and Speaker of the Legislature: “this stated to draw the attention to the insecurity of the press people. It is not necessary for the press to always support the government and neither should it resort to terror tactics if the press is critical of it.” Similarly, in its March 16th, 1956, issue, a Jammu weekly, Sach, beseeched the populace of Jammu to salvage democracy from the tyrannical and fascist yoke of the ruling clique.

It is highly questionable that the government which replaced that of Sheikh Mohammad Abdullah represented the political and economic aspirations of the people. I might also add that those inimical to Abdullah’s politics in 1953 leveled allegations of sedition and subversion against him for which they claimed to have “unimpeachable evidence.” That purportedly “unimpeachable evidence” was never presented, let alone brandished, making it nigh impossible for the powers-that-be to substantiate the allegations leveled against him.

(Nyla Ali Khan is a visiting professor at the University of Oklahoma. She earned her PhD in Post-colonial literature from OU. She is a member of the Scholars Strategy Network. She has written several books including The Fiction of Nationality in an Era of Transnationalism (Routledge, 2005), Islam, Women, and Violence in Kashmir: Between India and Pakistan (Palgrave Macmillan, 2010), Parchment of Kashmir: History, Society, and Polity (Palgrave Macmillan, 2012), and The Life of a Kashmiri Woman: Dialectic of Resistance and Accommodation. Dr. Khan lives in Edmond with her husband Dr. Khan a practicing Rheumatologist and their daughter.)