by JOHN GOWLETT

In pursuit of knowledge, the evolution of humanity ranks with the origins of life and the universe. And yet, except when an exciting find hits the headlines, palaeoanthropology and its related fields have gained far less scientific support and funding – particularly for scientists and institutions based in the African countries where so many landmark discoveries have occurred.

One of the first was made a century ago in Taung, South Africa, by mineworkers who came across the cranium of a 2.8 million-year-old child with human-like teeth. Its fossilised anatomy offered evidence of early human upright walking – and 50 years later, in the Afar region of northern Ethiopia that would become a hotspot for ancient human discovery, this understanding took another leap backwards in time with the discovery of Lucy.

The part-skeleton of this small-bodied, relatively small-brained female captured the public’s imagination. Lucy the “paleo-rock star” took our major fossil evidence for bipedal walking, human-like creatures (collectively known as hominins) beyond 3 million years for the first time. The race to explain how humans became what we are now was well and truly on.

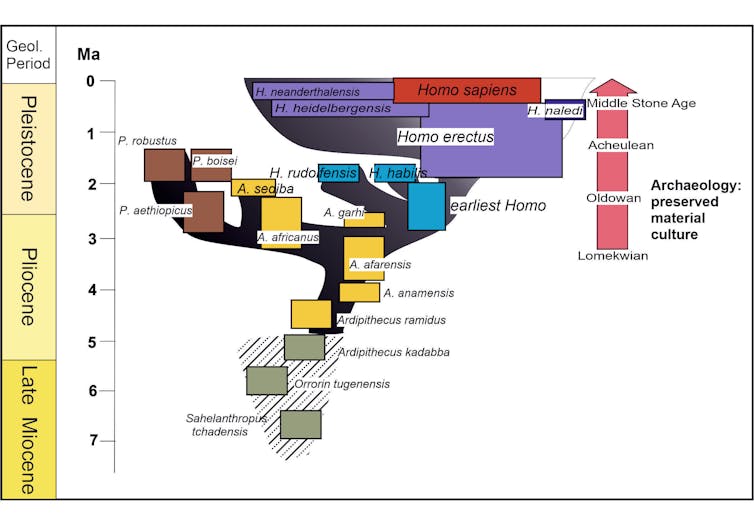

Since then, the picture has changed repeatedly and dramatically, shaped by waves of new fossil discovery, technology and scientific techniques – often accompanied by arguments about the veracity of claims made for each new piece of the puzzle.

Even the term “human” is arguable. Many scholars reserve it for modern humans like us, even though we have Neanderthal genes and they shared at least 90% of our hominin history from its beginnings around 8 million years ago. The essence of hominin evolution ever since has been gradual change, with occasional rapid phases. The record of evolution in our own genus, Homo, is already full enough to show we cannot separate ourselves with hard lines.

Nonetheless, there is enough consensus to thread the story of human evolution all the way from early apes to modern humanity. Most of this story centres on Africa, of course, where countries such as Kenya, South Africa and Ethiopia are rightly proud of their heritage as “cradles of humankind” – providing many of their schoolchildren with a much fuller answer then those in the west to this deceptively simple question: how did we get here?

Early apes to ‘hominisation’ (around 35m to 8m years ago)

The story of human evolution usually starts at the point our distant ancestors began to separate from the apes, whose own ancestors are traceable from at least 35 million years ago and are well attested as fossils. Around 10 million years ago, the Miocene world was warm, moist and forested. Apes lived far and wide from Europe to China, though we have found them especially in Africa, where sediments of ancient volcanoes preserve their remains.

This world was soon to be disrupted by cooling temperatures and, in places, great aridity – best seen around the Mediterranean, where continental movements closed off the Straits of Gibraltar and the whole sea evaporated several times, leaving immense salt deposits under the floor of the modern sea. Widespread drying was reported from around 7 to 6 million years ago, leading to a stronger expression of seasons in much of the world, and changes in plant and animal communities.

The Conversation for more