The rise and fall of globalisation: the battle to be top dog (part I)

by STEVE SCHIFFERES

For nearly four centuries, the world economy has been on a path of ever-greater integration that even two world wars could not totally derail. This long march of globalisation was powered by rapidly increasing levels of international trade and investment, coupled with vast movements of people across national borders and dramatic changes in transportation and communication technology.

According to economic historian J. Bradford DeLong, the value of the world economy (measured at fixed 1990 prices) rose from US$81.7 billion (£61.5 billion) in 1650, when this story begins, to US$70.3 trillion (£53 trillion) in 2020 – an 860-fold increase. The most intensive periods of growth corresponded to the two periods when global trade was rising fastest: first during the “long 19th century” between the end of the French revolution and start of the first world war, and then as trade liberalisation expanded after the second world war, from the 1950s up to the 2008 global financial crisis.

Now, however, this grand project is on the retreat. Globalisation is not dead yet, but it is dying.

Is this a cause for celebration, or concern? And will the picture change again when Donald Trump and his tariffs of mass disruption leave the White House? As a longtime BBC economics correspondent who was based in Washington during the global financial crisis, I believe there are sound historical reasons to worry about our deglobalised future – even once Trump has left the building.

Trump’s tariffs have amplified the world’s economic problems, but he is not the root cause of them. Indeed, his approach reflects a truth that has been emerging for many decades but which previous US administrations – and other governments around the world – have been reluctant to admit: namely, the decline of the US as the world’s no.1 economic power and engine of world growth.

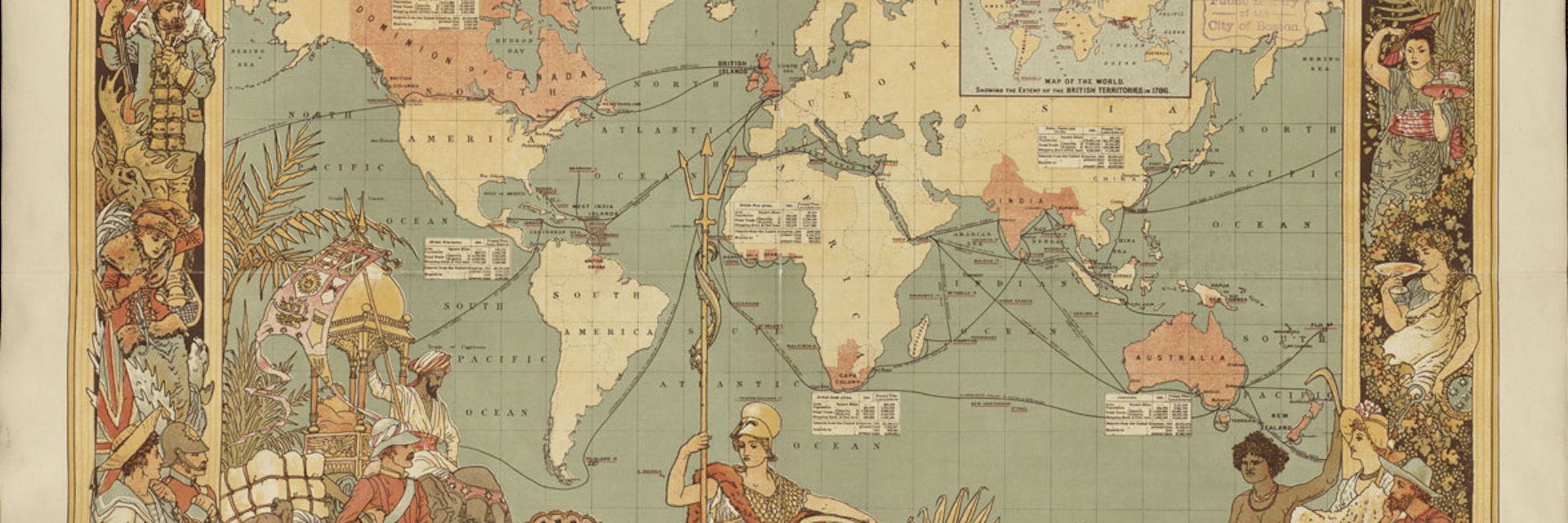

In each era of globalisation since the mid-17th century, a single country has sought to be the clear world leader – shaping the rules of the global economy for all. In each case, this hegemonic power had the military, political and financial power to enforce these rules – and to convince other countries that there was no preferable path to wealth and power.

But now, as the US under Trump slips into isolationism, there is no other power ready to take its place and carry the torch for the foreseeable future. Many people’s pick, China, faces too many economic challenges, including its lack of a truly international currency – and as a one-party state, nor does it possess the democratic mandate needed to gain acceptance as the world’s new dominant power.

The Conversation for more

The rise and fall of globalisation: why the world’s next financial meltdown could be much worse with the US on the sidelines (part II)

by STEVE SCHIFFERES

Globalisation has always had its critics – but until recently, they have come mainly from the left rather than the right.

In the wake of the second world war, as the world economy grew rapidly under US dominance, many on the left argued that the gains of globalisation were unequally distributed, increasing inequality in rich countries while forcing poorer countries to implement free-market policies such as opening up their financial markets, privatising their state industries and rejecting expansionary fiscal policies in favour of debt repayment – all of which mainly benefited US corporations and banks.

This was not a new concern. Back in 1841, German economist Friedrich List had argued that free trade was designed to keep Britain’s global dominance from being challenged, suggesting:

When anyone has obtained the summit of greatness, he kicks away the ladder by which he climbs up, in order to deprive others of the means of climbing up after him.

By the 1990s, critics of the US vision of a global world order such as the Nobel-winning economist Joseph Stiglitz argued that globalisation in its current form benefited the US at the expense of developing countries and workers – while author and activist Naomi Klein focused on the negative environmental and cultural consequences of the global expansion of multinational companies.

Mass left-led demonstrations broke out, disrupting global economic meetings including, most famously, the World Trade Organization (WTO) in 1999. During this “battle of Seattle”, violent exchanges between protesters and police prevented the launch of a new world trade round that had been backed by then US president, Bill Clinton. For a while, the mass mobilisation of a coalition of trade unionists, environmentalists and anti-capitalist protesters seemed set to challenge the path towards further globalisation – with anti-capitalism “Occupy” protests spreading around the world in the wake of the 2008 financial crash.

The Conversation for more