by THOM HARTMANN

The founders’ true intent behind the right to bear arms wasn’t liberty—it was control, oppression, and the preservation of slavery.

One mass shooting after another, one accidental child death after another tears through this country on an almost daily basis. Once again, lawmakers hide behind “thoughts and prayers,” while clinging to an amendment that has been twisted beyond recognition. But to understand why the Second Amendment exists at all, we must strip away the myths and confront a brutal truth: it was not written to safeguard freedom, but to preserve slavery.

The militias it enshrined were never about defending homes from tyrants abroad but about keeping human beings in chains at home. Until America reckons with this history, we will remain shackled to its bloody legacy.

So, let’s clear a few things up.

The real reason the Second Amendment was ratified, and why it says “state” instead of “country” (the framers knew the difference—see the 10th Amendment), was to preserve the slave-patrol militias in the Southern states, an action necessary to get Virginia’s vote to ratify the Constitution.

It had nothing to do with making sure mass murderers could shoot up public venues and schools. Founders, including Patrick Henry, George Mason, and James Madison, were totally clear on that, and we all should be too.

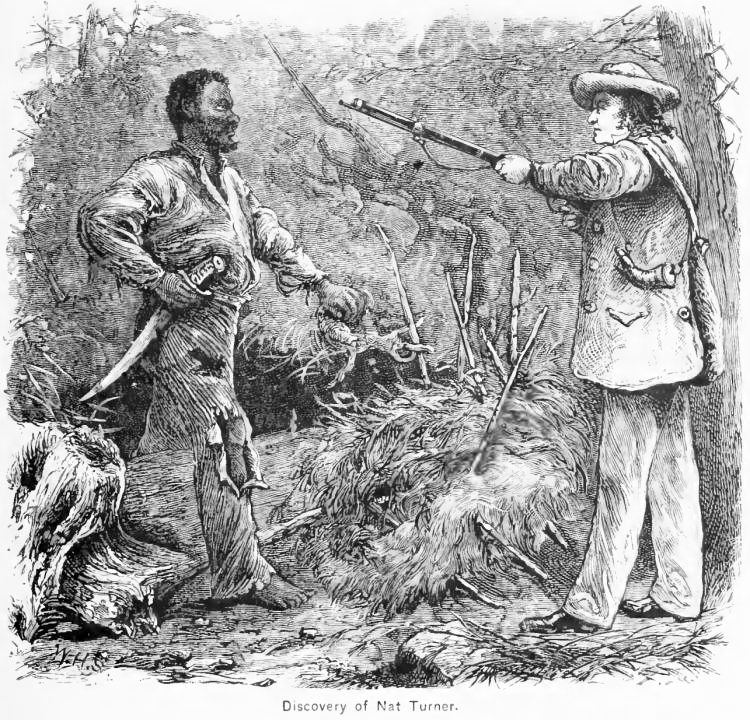

In the beginning, there were the militias. In the South, they were called “slave patrols” and were regulated by the states.

In Georgia, for example, a generation before the American Revolution, laws were passed in 1755 and 1757 that required all plantation owners or their male white employees to be members of the Georgia Militia, and for those armed militia members to make monthly inspections of the quarters of all slaves in the state. The law defined which counties had which armed militias and required armed militia members to keep a keen eye out for slaves who may be planning uprisings.

As Carl T. Bogus wrote for the University of California Law Review in 1998, “The Georgia statutes required patrols, under the direction of commissioned militia officers, to examine every plantation each month and authorized them to search ‘all Negro Houses for offensive Weapons and Ammunition’ and to apprehend and give twenty lashes to any slave found outside plantation grounds.”

It’s the answer to the question raised by the character played by Leonardo DiCaprio in Django Unchained when he asks, “Why don’t they just rise up and kill the whites?” It was a largely rhetorical question because every Southerner of the era knew the answer: Well-regulated militias kept enslaved people in chains.

Sally E. Hadden, in her brilliant and essential book Slave Patrols: Law and Violence in Virginia and the Carolinas, notes that, “Although eligibility for the Militia seemed all-encompassing, not every middle-aged white male Virginian or Carolinian became a slave patroller.” There were exemptions so “men in critical professions,” like judges, legislators, and students, could stay at their work. Generally, though, she documents how most Southern men between ages 18 and 45—including physicians and ministers—had to serve on the slave patrol in the militia at one time or another in their lives.

And slave rebellions were keeping the slave patrols busy.

Wiki Observatory for more