by KHALED AHMED

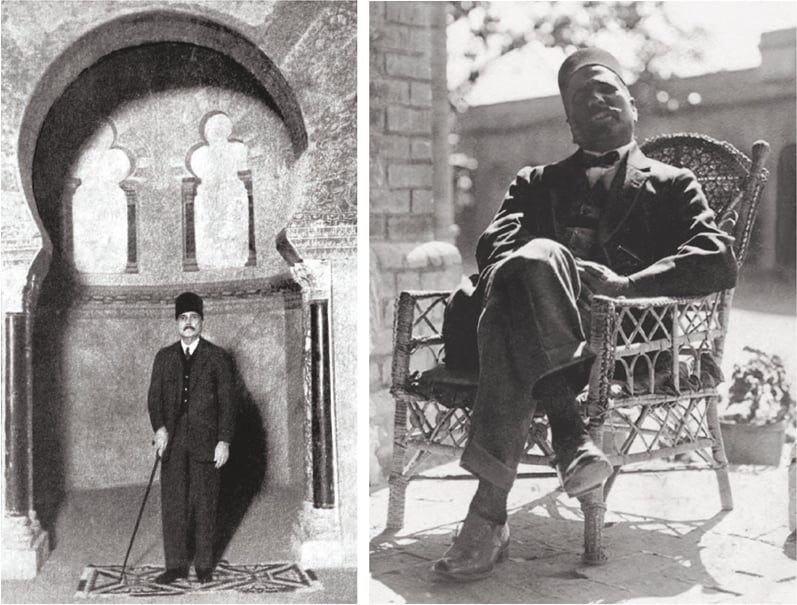

Pakistan’s ideological journey has reshaped the great poet philosopher Allama Muhammad Iqbal into a patron of its hardening worldview. Reviewing how he has been ‘reinterpreted’ into an ideological platitude is now hazardous because of his state-approved and clerically-backed identity as an orthodox thinker opposed to all modernist revision. At times, secular commentators longing for an identity rollback consign him to the category of ‘orthodox’ while praising Sir Syed Ahmad Khan as the true modernist. There is, however, steady evidence from his life that defies this orthodox labeling.

The climactic moment in Iqbal’s relationship with Pakistan came on December 25, 1986; some 48 years after his death. It happened during a national seminar presided over by General Ziaul Haq in Karachi on the birth anniversary of the founder of the state, Quaid-i-Azam Mohammad Ali Jinnah. The topic of the seminar was, What is the Problem Number One of Pakistan? Present among the invitees was the son of Allama Iqbal, then a sitting judge of the Supreme Court of Pakistan. In his speech on the occasion, Justice Javed explained why his father was opposed to Hudood (Quranic punishments) which Gen Zia had promulgated in Pakistan.

The controversial phrasing from the Sixth Lecture in Allama Iqbal’s book, The Reconstruction of Religious Thought in Islam, was: “The Shariat values (Ahkam) resulting from this application (e.g. rules relating to penalties for crimes) are in a sense specific to that people; and since their observance is not an end in itself they cannot be strictly enforced in the case of future generations.”

The reaction from Gen Zia was dismissive of Allama Iqbal rather than the Hudood he had imposed to appease his vast hinterland of clerical support. He had gotten into trouble with the clergy when his Federal Shariat Court decided that since stoning to death (Rijm) was not mentioned in the Quran it could not be a Hadd, that is, a punishment in the Penal Code. He had to change the Court to retain Rijm.

But Iqbal was prophetic: Pakistan has not stoned a single woman to death despite Rijm being on the statute book, nor has it been able to chop off hands for stealing. More literalist Iran gave up the ghastly practice of Rijm in 2014.

Pakistan is disturbed today by the continuing practice of bank interest after the Federal Shariat Court banned it in 1991 as Riba (usury) specifically mentioned in the Quran as also by Aristotle in his Nicomachian Ethic. Islamic banking which actually excludes the taking of Riba does so under a policy of complex self-confessed Heela (subterfuge).

In his publication Ilmul Iqtisad (1904), Iqbal’s first book in Urdu as an introduction to how a modern economy worked, he explained and clearly accepted bank interest as the lifeblood of commerce, knowing that it was considered banned by the clerics and accounted for so few Muslims in India’s commercial sector. He did so by accepting Sir Syed Ahmad Khan’s view that “interest-banking was not the same as Riba/usury”.

Dawn for more