by DONALD C. JOHANSON & YOHANNES HAILE-SELASSIE

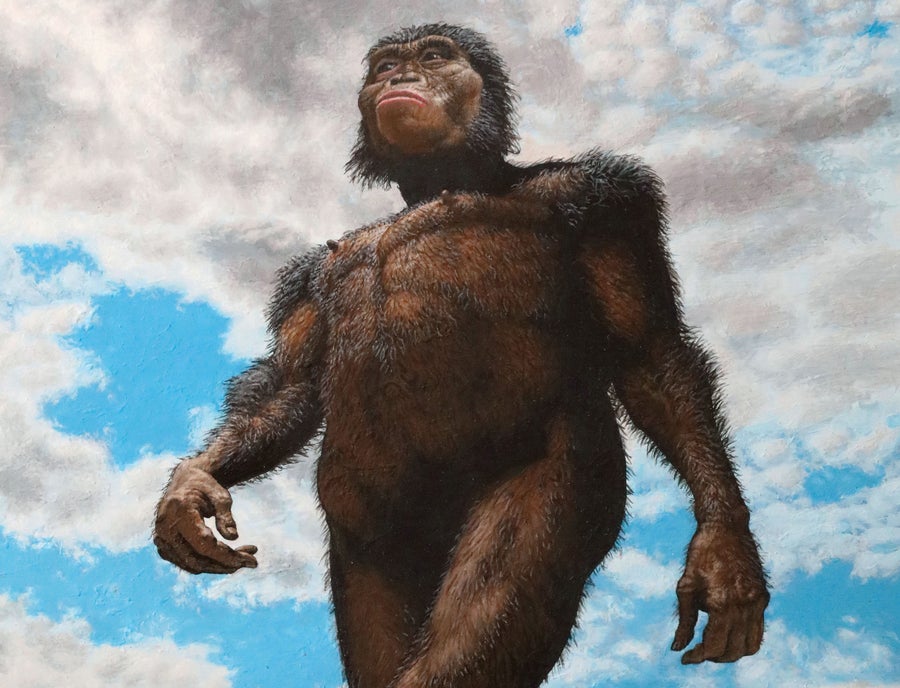

Every once in a great while paleontological fieldwork turns up a fossil so extraordinary that it revolutionizes our understanding of the origin and evolution of an entire branch of the tree of life. Fifty years ago one of us (Johanson) made just such a discovery on an expedition to the Afar region of Ethiopia. On November 24, 1974, Johanson was out prospecting for fossils of human ancestors with his graduate student Tom Gray, eyes trained on the ground, when he spotted a piece of elbow with humanlike anatomy. Glancing upslope, he saw additional fragments of bone glinting in the noonday sun. In the weeks, months and years that followed, as the expedition team worked to recover and analyze all the ancient bones eroding out of that hillside, it became clear that Johanson had found a remarkable partial skeleton of a human ancestor who had lived some 3.2 million years ago. She was assigned to a new species, Australopithecus afarensis, and given the reference number A.L.288-1, which stands for “Afar locality 288,” the spot where she, the first hominin fossil, was found. But to most people, she is known simply by her nickname, Lucy. With the discovery of Lucy, scientists were forced to reconsider key details of the human story, from when and where humanity got its start to how the various extinct members of the human family were related to one another—and to us. Her combination of apelike and humanlike traits suggested her species occupied a key place in the family tree: ancestral to all later human species, including members of our genus, Homo.

It can be precarious to hang such a pivotal argument on a single fossil individual. But in the half a century since Lucy’s unveiling, many more specimens of Au. afarensis have been found. Together they provide an exceptionally detailed record of this ancient species, revealing where it roamed, how it lived, how its members differed from one another and how long it endured before going extinct.

Scientific American for more