by CONOR GALLAGHER

“An industrial economy’s decline usually provides a grab bag of opportunities for financial predators and vulture funds.”

– Michael Hudson, “The Destiny of Civilization”

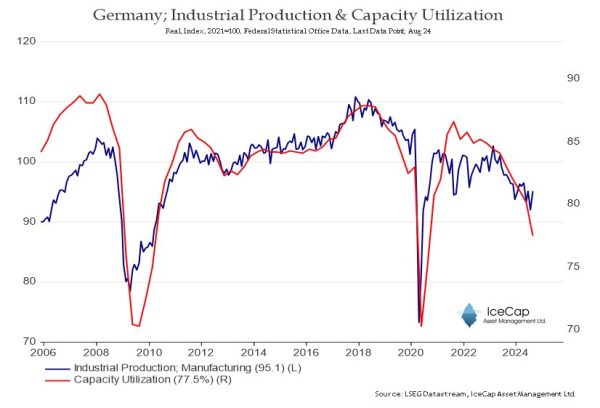

And so it goes in Germany where the decimation of the country’s industry and its working class continues apace. Volkswagen added to the carnage on Monday with plans to close three factories and potentially lay off tens of thousands of workers.

How are the “financial predators and vultures” doing? Quite well. Here are some numbers from WSWS:

While poverty is growing, at the top end of the scale the number of super-rich is on the rise. The annual ranking by Manager Magazin shows that the number of billionaires in Germany has recently risen by 23 to 249.

Manager Magazin has published a list of the 500 richest Germans and calculated that their private assets and wealth in 2023 amounted to a record €1.1 trillion, an increase of €53 billion compared to the previous year. This sum, €1.1 trillion, is almost two-and-a-half times the federal budget for the same year…about 0.6 percent of the population, own 45 percent of the country’s total wealth.

And Germany continues to become a much more unequal society with a Bundesbank survey finding that the top 10% of households have at least €725,000 ($793,000) of net assets and control more than half of the country’s wealth, while the bottom 40% of households have at most €44,000 of net assets.

What’s causing the surge in inequality and how have the wealthiest found ways to keep growing their fortunes while the national economy breaks down? Let’s take a look at the main drivers of inequality and then compare them to situation in Germany today.

Here’s Dutch economist Servaas Storm in a paper featured here at NC back in 2021 explaining the primary causes of increasing economic disparity:

The key driver of rising income inequality is the stagnation of real wage growth for the bottom 80% or so of U.S. households (Taylor and Ömer 2020). Real wage growth was suppressed below labour productivity growth, and this led to a secular decline in the share of wages (and a rise of profits) in national income. The main cause of the wage growth suppression has been the abandonment of full employment as the primary target of macro policy-making, in favour of inflation control, at the end of the 1970s. Fiscal policy was deprioritized in favor of monetary policy, conducted by independent central banks, single-mindedly focused on building credible reputations as inflation hawks, and counter-cyclical fiscal stabilization was made anathema by subjecting fiscal policy-making to rigid and deflationary rules, irrespective of the business cycle. For a period of time after the global financial crisis of 2008, austerity zealots, dreaming of expansionary fiscal consolidations, intensified the fiscal repression, bringing about one of the slowest and most costly economic recoveries from a crisis in history.

Labour markets were enthusiastically deregulated, with the explicit and generous approval of central banks and governments, to break the structural inflationary power of unions and to create a flexible reserve of surplus workers with no choice but to work in temporary low-wage jobs in what is now known as the ‘gig’ economy. Globalization and offshoring contributed to breaking the countervailing power of organized workers because they offered corporations (the threat of) an opt-out possibility that was not available to workers. Taken together, the change in macroeconomic policy regime produced a structurally low-inflation economy, based on ‘traumatised workers’ in precarious jobs, who could not plausibly fight for higher wages and more secure employment conditions, given their daily struggles and the systemic biases they are facing. The wellspring of cost-push inflation had been radically removed.

Stagnant wages and incomes for the 90% mean that income (and wealth) inequality rises and that aggregate household savings go up (as shown by Mian, Straub and Sufi). Higher household savings reduce consumption demand, which holds up fixed business investment for the domestic market. In effect, aggregate demand growth stagnates, and pressures for demand-pull inflation evaporate. With inflation (and expected inflation) being low in structural terms, central banks lower the interest rate, in accordance with the recommendations based on the monetary policy rules proposed by establishment economics.

The low interest rates, in turn, fuel asset-price bubbles, creating wealth gains for the rich, and over-indebtedness for the bottom 90% of households, which use cheap credit to finance essential expenses on education, medical care and housing. This reinforces wealth and income inequalities, and pushes up asset prices even more, but this does not lead to higher economic growth and better jobs, because the richest 10% use their savings and wealth gains not for investments in the real economy, but to speculate in financial markets. The past two decades have made it abundantly clear that the gains made by the top 10% in financial markets do not trickle down to the real economy.

Now let’s take some of Storm’s key points and see how they’ve been applied in Germany. In many ways the crises of the past four years — first the pandemic and then the self-inflicted wound of the country’s Russia policy — have put long-term trends into overdrive:

Stagnation of Real Wage Growth. “German wages set to rise at the fastest pace in more than a decade” announced a recent headline at Euronews. Sounds great, but if we dig in a little ways we get to this:

“The price-adjusted level of collective wages is still well below the peak value of 2020”, although about half of the purchasing power losses of previous years have been compensated for.

Ouch.

Naked Capitalism for more