by PAUL Le BLANC

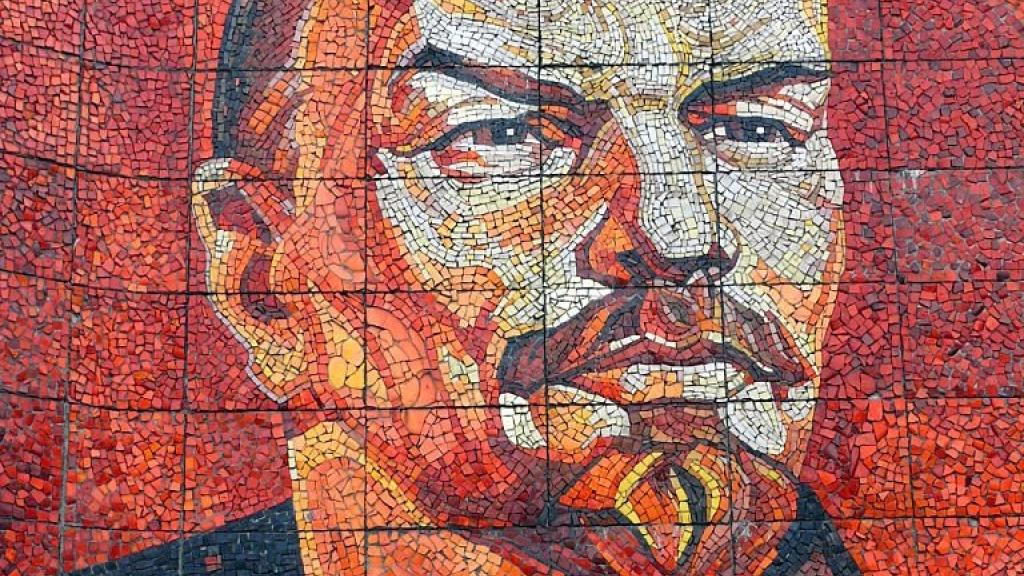

Vladimir Ilyich Ulyanov — known by his revolutionary alias, Lenin — was a central figure in the history of the twentieth century. He was a leader of the 1917 Russian Revolution and a founder of the modern Communist movement, who was perceived by millions of people either as Evil Incarnate or a Benevolent Genius. I would argue that he should be seen as a human being who can be shown to have made more than one serious mistake. But as Lenin himself noted, “he who never does anything never makes mistakes,” and Lenin did quite a lot. His development of Marxism’s revolutionary cutting edge has relevance for the future. I want to focus on some ways revolutionary activists can make use of his ideas today. The great African American poet, Langston Hughes, expressed his global impact in these lines:

Lenin walks around the world.

Black, brown, and white receive him.

Language is no barrier.

The strangest tongues believe him.

If we do it right, we can draw useful notions from what this comrade has to offer, as we face such realities as anti-racist upsurges, the multi-faceted escalation of feminist struggles, the immense challenges of climate change, wars in Gaza and Ukraine and elsewhere. In the United States, we have also been faced with the interrelated phenomena of mild socialist Bernie Sanders and super-capitalist Donald Trump. Rightward veering “Trumpism” poses an especially ominous threat — one that dovetails with the ascent of right-wing authoritarians around the world, such as Javier Milei in Argentina, until recently Jair Bolsanaro in Brazil, Viktor Orbán in Hungary, Narendra Modi in India, Vladimir Putin in Russia, and Recep Tayyip Erdo?an in Turkey. I will focus on the US electoral realities later in this presentation, because I am most familiar with them.

In the face of all this, what would Lenin do? To deal with this question adequately, I think it will help to broaden it. Is it possible for us to make use of Lenin’s ideas 100 years after his death, and if so — how? Another way of posing this question would be: “What would Lenin’s approach be to using Lenin’s basic orientation 100 years after his death?”

All the specifics of Lenin’s analyses cannot not simply be assumed to be applicable in the very different context of our time. At the heart of Lenin’s political approach is the notion that while the use of Marxist theory is essential for building revolutionary movements and struggles, it must be used not as a dogma, but as a guide to action. Related to this is the dialectical notion that “nothing is constant but change.” Essential to Lenin’s dialectics is also a recognition that continuities are blended intimately into the changes.

Another essential element in Lenin’s orientation involved the non-dogmatic utilization of historical materialism, which helps us see three realities: (1) economic development is central to the development of history; (2) the incredibly dynamic capitalist system is the dominant form of economy in modern times; and (3) class divisions are decisive, and under capitalism a small minority of capitalists secure immense wealth and power by exploiting the labor of, and squeezing wealth out of, the lives and labors of the great majority of people who make up the working class.

Despite multiple changes — for example, in the size and nature of the working class (which is bigger and more occupationally diverse than it used to be) and the structures and technologies associated with today’s capitalist system as a whole — the underlying dynamics of capitalism remain similar from Lenin’s time to ours. The three points I identified as part of historical materialism manifest themselves differently than was the case 100 years ago, but nonetheless they continue to operate and shape the reality of our own world.

Two essential elements were constant in Lenin’s approach. One was not to settle for simplistic and comforting dogmas, but instead to approach everything with a critical mind, to base one’s understanding on what he called “stubborn facts,” seeking real information with a drive to keep learning and learning and learning about the complexities of reality. A second essential element involved a refusal to settle for Marxist analysis as simply a passive contemplation of what and how things are. Lenin refused to detach social, economic and political analysis from an activist engagement, from the restless and insistent question: what is to be done?

For Lenin — from the time he became a young Marxist activist to the end of his life — this added up to an insistence that we must not bow to the oppressive and exploitative powers-that-be, and that we must never submit to the transitory “realism” of mainstream politics. Instead, all political action should be measured by how it helps build working-class consciousness, the mass workers’ movement, and the revolutionary organization necessary to overturn capitalism and lead to a socialist future.

Links for more