by LINA MOE

In 1524, a peasant uprising against grinding poverty and feudal rule swept across parts of what is now Germany, Austria and Switzerland. Though it was eventually crushed, the revolt gave rise to folk legends that endured for centuries, among them the story of a towering woman fighter. ‘Black Anna’, as she was known – likely based on the peasant leader Margaret Renner – is the central figure in the German artist Käthe Kollwitz’s striking graphic cycle, ‘The Peasants’ War’ (1901-1908). Black Anna is depicted rallying her forces, her outstretched arms directing a line of armed men who surge across a field. The prints dramatize a dialectic of oppression and resistance: elsewhere we see the upward swoop of armed men rushing through a castle entryway, a mother bending over her dead son.

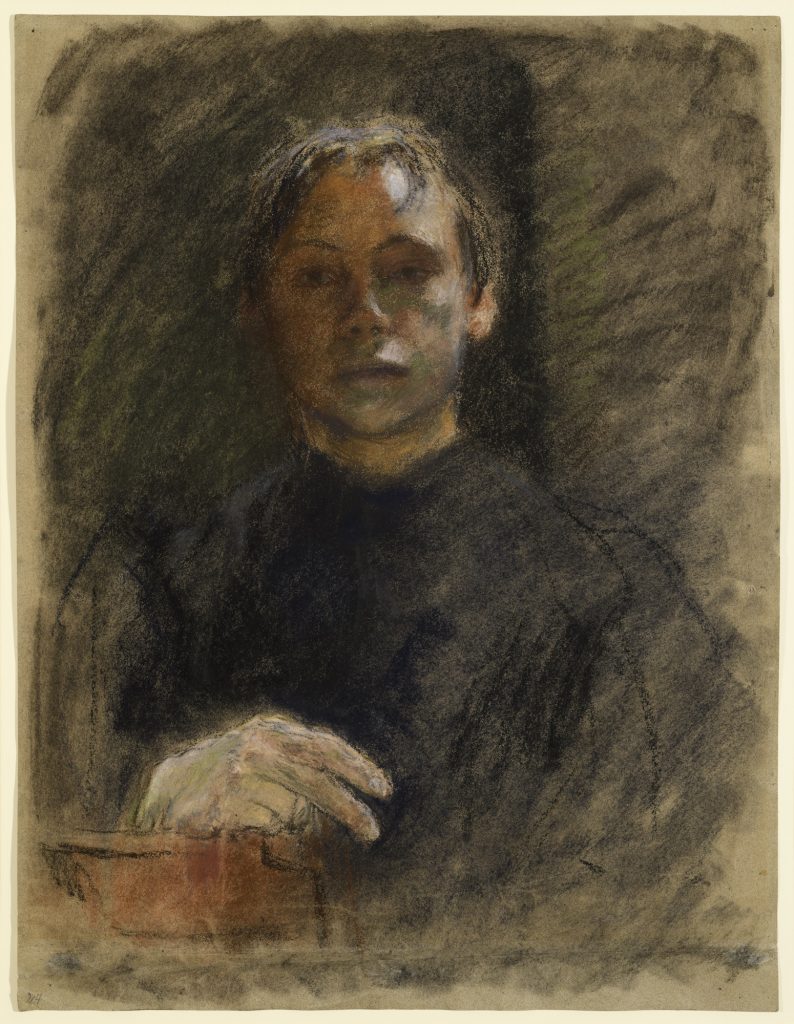

Kollwitz herself was an unusual figure in many respects. A female artist of the early twentieth century who was widely recognized during her lifetime, her primary medium was printing rather than painting. Committed to narrative and representation in a heyday of abstraction, Kollwitz valued sincerity over irony, distancing her from the key artistic movements – Dada, Neue Sachlichkeit – of the period. Never a member of the SPD or KPD, she nonetheless produced socially engaged art centred on the working class. A survey of her work currently showing at the Museum of Modern Art in New York – encompassing early paintings, numerous self-portraits, the major graphic series, the popular posters – brings these idiosyncrasies into relief. It also reveals some of the animating tensions of her oeuvre, among them the use of portraiture as means to represent collectivities, and of an intimate visual language to address world-historic themes.

She was born Käthe Schmidt in Königsberg in 1867, in what was then Prussia, and raised in an educated, upper-middle-class family of socialist and dissident religious convictions. Though neither of Kollwitz’s sisters worked outside the home, her father encouraged her to pursue an artistic career, paying for years of training and travel. Her ambitions were shaped by this paternal support, as well as encounters with socialism and feminism – formative writings included August Bebel’s Women and Socialism and the journalism of Clara Zetkin. In 1891, she married a doctor, Karl Kollwitz, and the couple settled in the working-class district of Prenzlauer Berg in Berlin.

SideCar – New Left Review for more