by NISHTHA GAUTAM

IMAGE/Wikimedia Commons

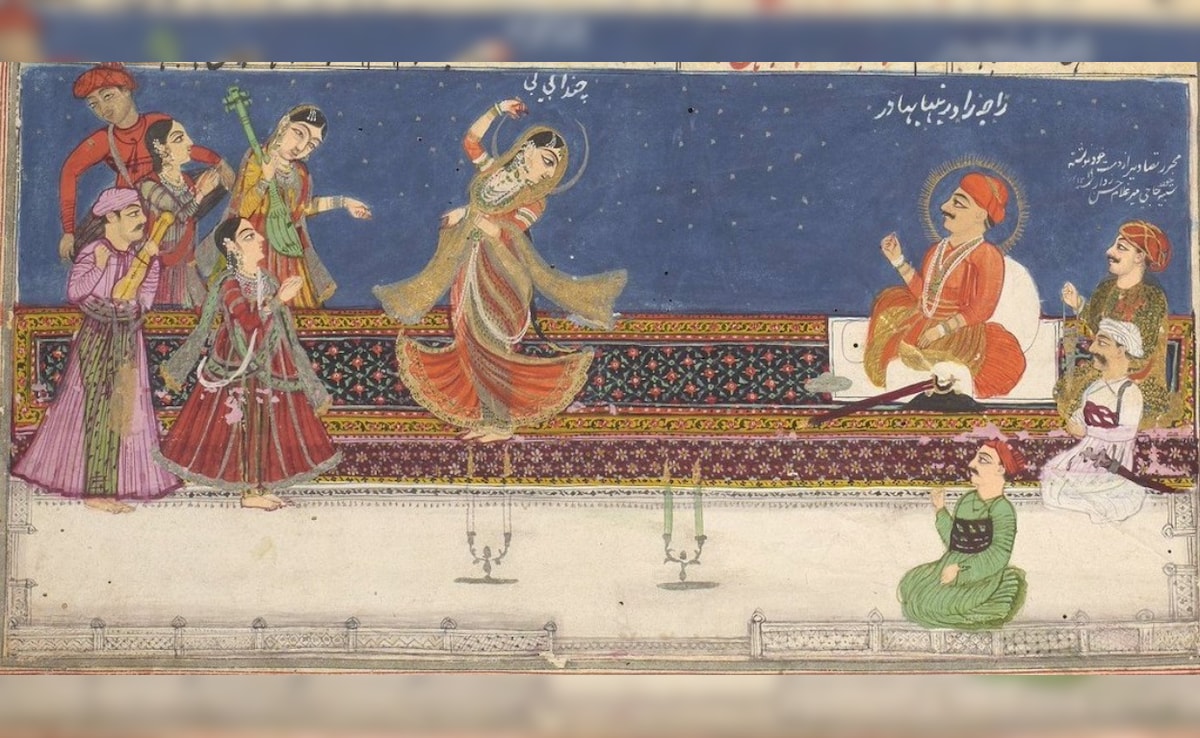

“Delhi was a city of courtesans who wielded extraordinary influence in the court,” exclaimed a Banarasi professor of literature visiting the city from London, where she teaches and writes. This statement from earlier this year echoes now in a strange twist of irony. Delhi still remains a city of courtesans, and nowadays, there’s mujra on everyone’s mind.

What is mujra? With etymological roots in Arabic, mujra is a gesture of paying respects. While the term now refers to a dance of courtesans, the Arabic mothership phrase salam ma-jara literally translates as ‘greetings of praise that have been offered’. Because it is the rich and powerful that are worthy of exaggerated praise, women and men skilled in poetry, music and dance put up performances of mujra in which they offered salam or salutations to their existing or potential patrons. Similar acts of paying respects were observed at Sufi shrines, both minor ones like that of Loh Langar Shah in Mangalore, and prominent ones like the resting place of Khwaja Moinuddin Chishti in Ajmer.

Patronage As Power

Patronage ensures survival. It is also the route to power. Nobody knows it better than women artists. One of the earliest women Urdu poets, Mah Laqa Bai of Hyderabad, was an adopted daughter of the prime minister of Deccan. Skilled in words and weaponry alike, she was to become one of the highest-ranking courtiers in the courts of the second and third Nizam of Hyderabad. One of the earliest recorded mujra performances dates back to September 20, 1820. Mah Laqa Bai performed for Nizam Sikandar Asaf Jah at his Moti Mahal Palace. By this time, mujra had become integral to the courtly savoir-faire.

The mujra performed by a tawaif, or courtesan, was a structured performance that began with a specific form of greeting-saluting seven times in a style similar to courtly salutations made to the king. The music and dance performance to entertain and pay obeisance to powerful patrons, together with this salami, which is the actual ‘mujra‘, became known as mujra in common parlance. Again, contrary to popular notions, singing and not necessarily the dance was the central piece of a mujra. The tawaif sang either a ghazal or a Hindustani musical form like Dadra, Thumri, Hori, Kajri etc. Often, these performances were an occasion to showcase an upcoming poet’s talents.

The Real Mujra

Contrary to popular belief, a mujra performance is not necessarily a prequel to amorous or sexual liaisons. It may, however, lead to those, just like coffee dates. The mujra performances were stigmatised for various reasons even before the tawaifs descended hopelessly into the world of prostitution, thanks to the British dismantling the Sultanate and regional courts. According to the records of Har Bilas Sarda, a civil servant writing in the early twentieth century, dancers and musicians – male and female – used to perform every Thursday at Khwaja Moinuddin Chishti’s tomb in Ajmer. These musical assemblies were decried as “secular festivals” by religious fundamentalists. Despite resistance and attempts by even the shrine’s management, these performances continued in Ajmer till the 1970s. Mujra wasn’t Islamic enough.

Another interesting fact about mujra involves the religion of the people concerned – performers as well as the audience. The patrons were, obviously, the rich and powerful; they could be Hindu zamindars, Sikh rulers, Christian British soldiers, or Muslim aristocracy. Similarly, the performers could be either Hindu or Muslim. The songs they sang could be in Persianate Urdu about courtly love, or in Brajbhasha about the divine love of Krishna and Radha. Kathak, the classical dance form associated with mujra, is also the dance of devotion, with aesthetic roots in Bharat’s Natyshastra. It is the Hindi film industry’s fetishisation of the mujra for its largely Hindu audience that seems to have rooted it solely in the Islamicate culture.

Mujra Has No Religion

A mujra performance can be seen as an arena where many patrons-men-used to compete for the favour of one woman, the tawaif. This asymmetry brought the aegis of power into the hands of a woman in a rather public fashion. The site of the mujra, therefore, was also a site of subversion in a patriarchal society. The mujra-performing tawaifs were some of the most effective ground workers in India’s freedom struggle. Their influence, resources, and access allowed revolutionaries to plan and execute their acts of resistance.

Today, mujra has become a metaphor for the practice of seeking benefits in return for sexual favours. Stripped of its cultural and aesthetic context, mujra can be any movement of the body in a sexually charged assembly. Even music is optional. It is this version of mujra that has crept into our socio-political imagination. The biggest problem with such a formulation is also the simplest: ignorance.

NDTV for more