by KENAN MALIK

A century after his birth, EP Thompson’s empathy with those facing scorn and condescension is more relevant than ever

It is not often that, as a teenager, you get captured by a 900-page tome (unless it has “Harry Potter” in the title). Even less when it is a dense book of history, telling in meticulous detail stories of 18th-century weavers and colliers, shoemakers and shipwrights.

Yet I can even now picture myself first stumbling across EP Thompson’s The Making of the English Working Class in a bookshop. I had no idea about its cultural significance or its place in historiographic debates. I would not have known what “historiography” meant, or even that such a thing existed. But I can still sense the thrill in opening the book and reading in the first paragraph: “The working class did not rise like the sun at an appointed time. It was present at its own making.” I did not know it was possible to write about history in that way.

I still have that old, battered, pencil-marked Pelican edition with George Walker’s engraving of a Yorkshire miner on the cover; a book into which I continue to dip, for the sheer pleasure of Thompson’s prose and because every reading provides a fresh insight.

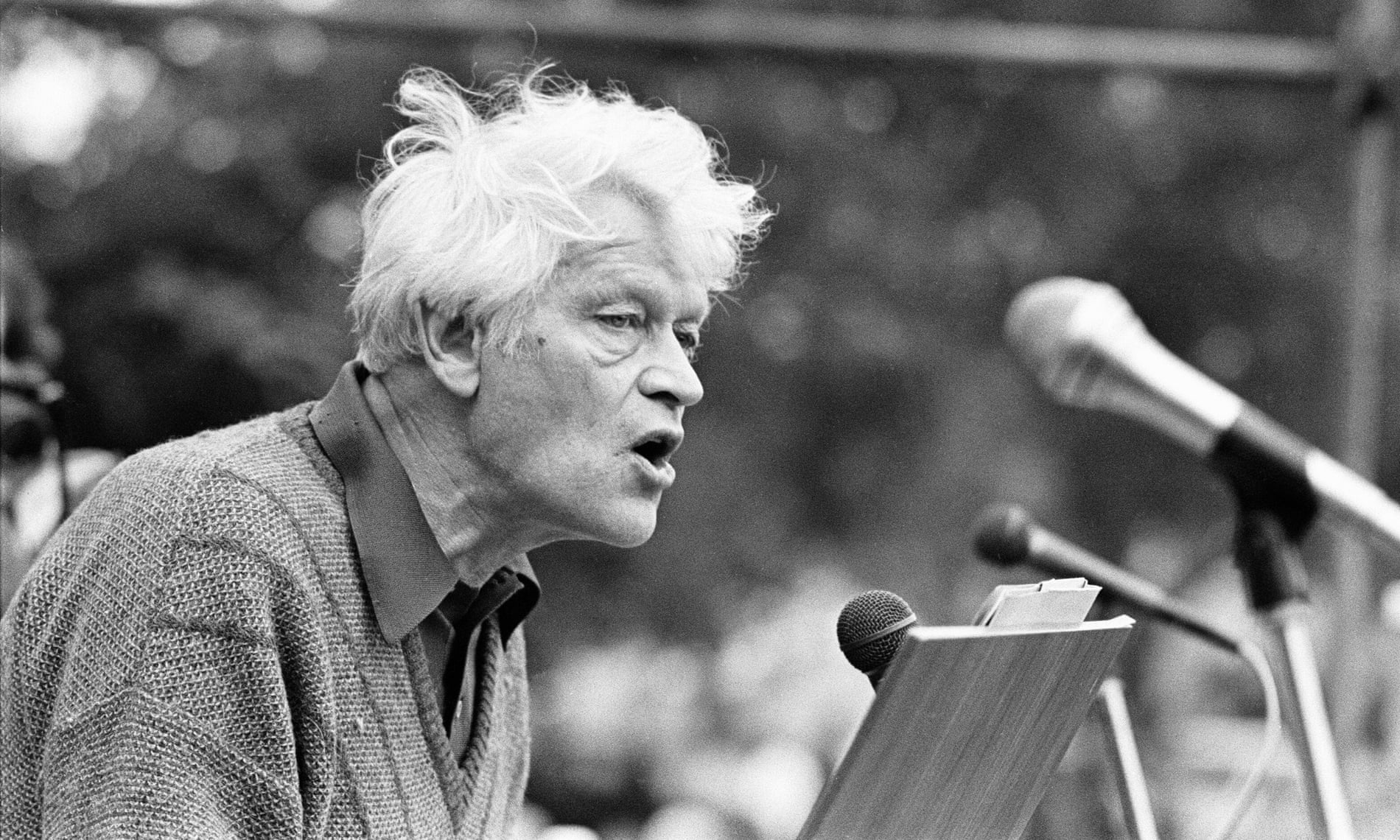

Were Thompson still alive, he would have been 100 on Saturday. The occasion was marked by a small conference, in Halifax, a town in which Thompson lived for many years, while teaching in Leeds and writing his book. But beyond that, there has been little fanfare.

Still in print more than 60 years after it was first published, The Making of the English Working Class has acquired an almost mythic status. Thompson himself, though, has faded from our cultural horizon. The historian Robert Colls noted a decade ago that when, in 2013, Jeremy Paxman asked, in the semi-finals of University Challenge, who wrote The Making of the English Working Class?, “nobody knew”.

Thompson’s most influential work was written at the high tide of working-class influence in British politics. Today, the old industrial working class, about the making of which Thompson wrote, has largely been unmade, politically marginalised and stripped of its social power. Few regard class as a fertile concept in historical thinking, fewer still as a foundation for progressive politics. Yet the very shifts that have led to the contemporary neglect of Thompson also make his arguments significant.

At the heart of Thompson’s book is a reimagining of class and class consciousness. Class, he wrote, was “not a thing”, or a “structure”, but a “historical phenomenon” through which the dispossessed “as a result of common experiences (inherited or shared), feel and articulate the identity of their interests as between themselves, and as against other men whose interests are different from (and usually opposed to) theirs”.

The Guardian for more