by DOUGLAS FOX

Global warming is so rampant that some scientists say we should begin altering the stratosphere to block incoming sunlight, even if it jeopardizes rain and crops

On the crisp afternoon of February 12, 2023, two men parked a Winnebago by a field outside Reno, Nev. They lit a portable grill and barbecued a fist-sized mound of yellow powdered sulfur, creating a steady stream of colorless sulfur dioxide (SO2) gas. Rotten-egg fumes permeated the air as they used a shop vac to pump the gas into a balloon about the diameter of a beach umbrella. Then they added enough helium to the balloon to take it aloft, attached a camera and GPS sensor, and released it into the sky. They tracked the balloon for the next several hours as it rose into the stratosphere and drifted far to the southwest, crossing over the Sierra Nevada Mountains before popping and releasing its gaseous contents. The contraption plummeted into a cow pasture near Stockton, Calif.

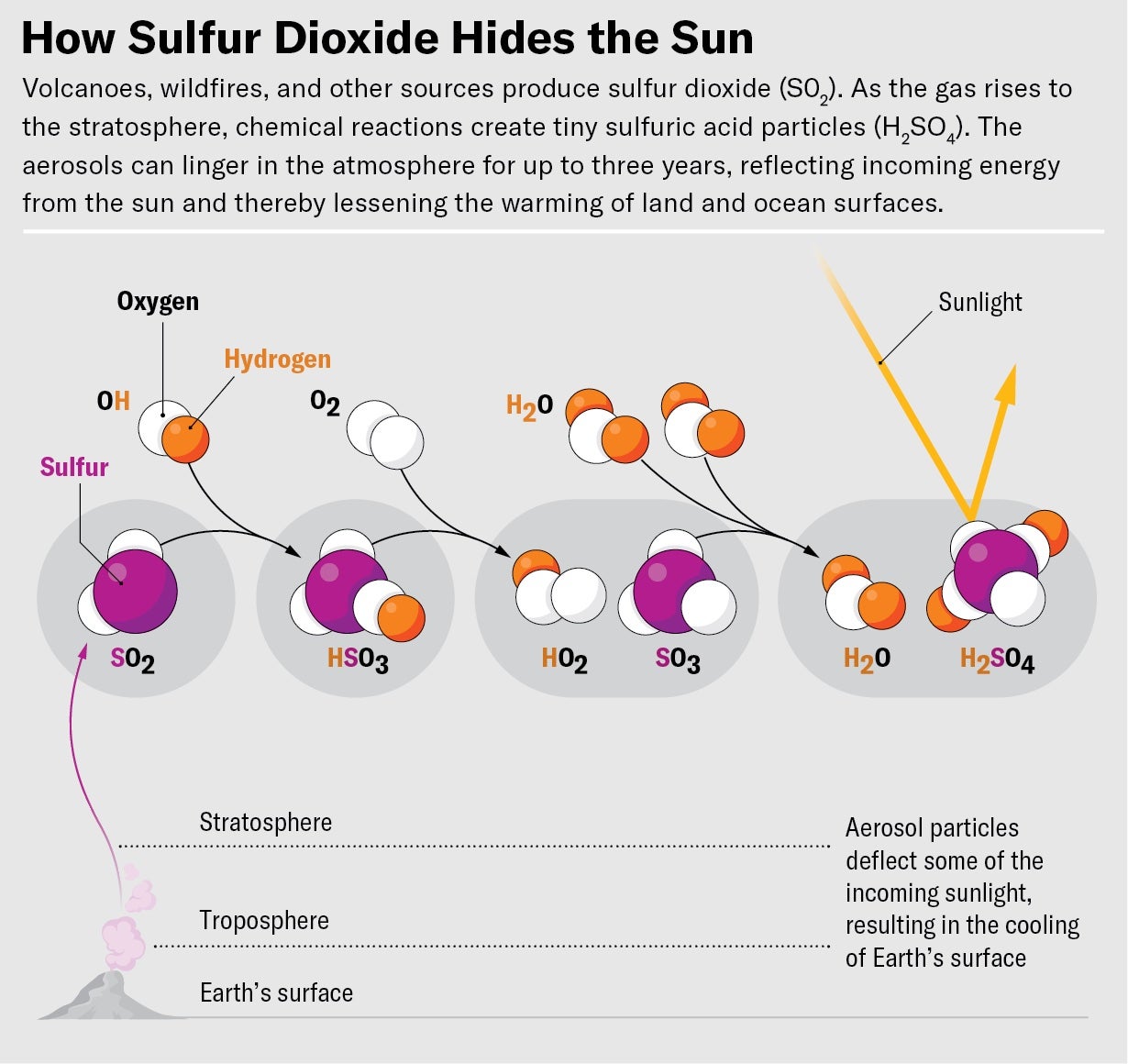

The balloon released only a few grams of SO2, but the act was a brazen demonstration of something long considered taboo—injecting gases into the stratosphere to try to slow global warming. Once released, SO2 reacts with water vapor to form droplets that become suspended in the air—a type of aerosol—and act as tiny mirrors, reflecting incoming sunlight back to space. Luke Iseman and Andrew Song, founders of solar geoengineering company Make Sunsets, had sold “cooling credits” to companies and individuals; a $10 purchase would fund the release of a gram of SO2, which they said would offset the warming effects of a metric ton of atmospheric carbon dioxide for a year. They had planned a launch in Mexico but switched to the U.S. after the Mexican government forbade them.

Many people recoil at the notion of solar geoengineering, or solar radiation management (SRM), as it’s often called. The idea that humans should try to fix the atmosphere they’ve messed up by messing with it some more seems fraught with peril—an act of Faustian arrogance certain to backfire. But as it becomes clear that humans are unlikely to reduce emissions quickly enough to keep global warming below 1.5 degrees Celsius, some scientists say SRM might be less scary than allowing warming to continue unabated. Proposals for cooling the planet are becoming more concrete even as the debate over them grows increasingly rancorous.

SRM replicates a natural phenomenon created by large volcanic eruptions. When Mount Pinatubo erupted in the Philippines in 1991, it blasted 20 million tons of SO2 into the stratosphere, creating an “aerosol parasol” that cooled the planet by about 0.5 degree C over the next year or so before the droplets settled back to Earth. Studies suggest that if SRM were deployed at sufficient scale—maybe one quarter of a Pinatubo eruption every year, enough to block 1 or 2 percent of sunlight—it could slow warming and even cool the planet a bit. Its effects would be felt within months, and it would cost only a few billion dollars annually. In comparison, transitioning away from fossil fuels is expected to take decades, and the CO2 emitted until then could make warming worse. Using machines to remove billions of tons of CO2 from the skies, a process called direct-air capture, could slow warming but would be fighting itself—the machines might increase the world’s energy consumption by up to 25 percent, potentially creating more greenhouse gas emissions. Because SRM could produce effects quickly, it has political appeal. It’s “the only thing political leaders can do that would have a discernible influence on temperature within their term in office,” says Ken Caldeira, a climate scientist emeritus at the Carnegie Institution for Science, who is also a senior scientist at Breakthrough Energy, an organization founded by Bill Gates.

Caldeira and others say SRM should be pursued with extreme caution—if at all. It could noticeably whiten our blue sky. It could weaken the stratospheric ozone layer that protects us and Earth’s biosphere from ultraviolet radiation. It might change weather patterns and move the monsoons that water crops for billions of people. And it wouldn’t do anything to remedy other CO2-related problems such as ocean acidification, which is harming the ability of corals, shellfish and some plankton to form skeletons and shells.

Critics also say that the very idea of an escape hatch such as SRM could undermine support for reducing greenhouse gas emissions. Like a prescription drug, if SRM were used responsibly—temporarily and in small doses—it could be beneficial, easing what is likely to be a dangerously hot century or two and buying humanity some extra time to transition to renewable energy. But it also has potential for abuse. At higher doses it could increasingly distort the climate, altering weather patterns in ways that pit nation against nation, possibly leading to war.

For all these reasons, more than 400 scientists have signed an open letter urging governments to adopt a worldwide ban on SRM experiments. But other scientists are proceeding, if reluctantly. “All the scientists I know who are working on this—none of them want to be working on it,” says Alan Robock, a climatologist at Rutgers University. Robock, who previously showed the world how a nuclear winter could shroud Earth, studies SRM out of a sense of obligation. “If somebody’s tempted to do this in the future,” he says, they “should know what the consequences would be.”

Experts who support trials note that unabated warming is just as consequential. In a recent report, the World Meteorological Organization estimated a 66 percent chance that by 2027 the world’s average annual temperature will briefly exceed 1.5 degrees C above preindustrial levels—a dangerous threshold beyond which extreme damage to the environment occurs. On February 27, 2023, a few days after Iseman and Song sent barbecued sulfur into the sky, 110 climate scientists, including climate change pioneer James Hansen, published a different open letter urging government support for SRM research. The following day the United Nations called for international regulations that could pave the way for experimentation. And in June the Biden administration released a report outlining what an SRM research program could look like.

Even if SRM reduced average temperatures, it wouldn’t reset the climate to its preindustrial state, says David Keith, head of climate systems engineering at the University of Chicago, who has studied the idea for over two decades. But it could lessen the hurt coming for us.

The idea that humans can change the planet’s atmosphere for their own purposes has a long history. In 1962 the U.S. military started Project Stormfury, an attempt to weaken hurricanes by seeding their clouds with silver iodide particles. From 1967 to 1972 the U.S. Air Force dabbled in weather-control warfare over Vietnam and Laos; in a highly classified effort called Operation Popeye, several aircraft flew daily missions to spray lead and silver iodide powder into monsoon clouds. The goal was to increase rainfall, which would muddy up the Ho Chi Minh Trail, a network of coarse roads, interrupting Vietcong supply lines.

Almost as soon as scientists understood that rising CO2 could warm the planet, some of them proposed making Earth more reflective to counter the effect. In 1965 scientists reported to President Lyndon B. Johnson that warming caused by rising CO2 could be addressed by spreading reflective particles across the oceans. In 1974 Russian climatologist Mikhail Budyko suggested that injecting SO2 into the stratosphere via aircraft or rockets could reflect sunlight. This technology, he wrote, “should be developed without delay.” Perhaps surprisingly, these proposals did not include the idea of reducing emissions.

Scientific American for more