by SOHINI CHATTOPADHYAY

This book on a filmmaker as thoughtful as Benegal has reduced him into nothing more than a repository of thesis ideas for reluctant graduate students.

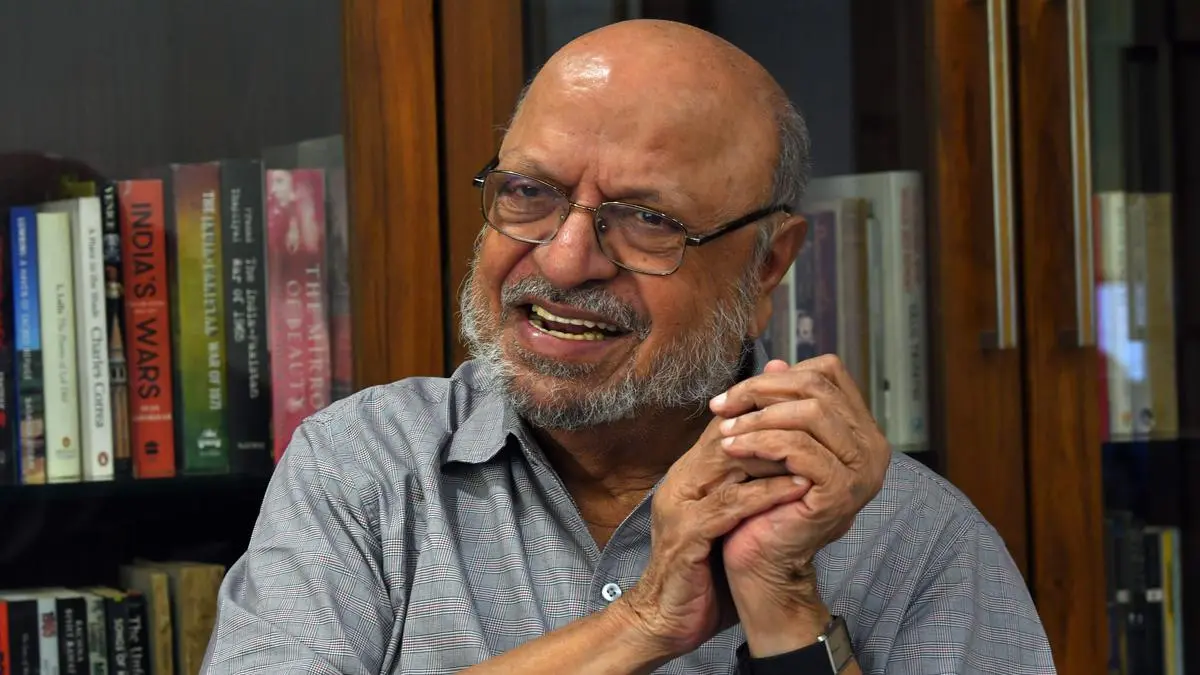

In 2024, Shyam Benegal’s debut feature film Ankur will turn 50. The story of the unrest in landed relations in the Telangana region of Madras Presidency from the late 1940s to mid-1950s that erupted into a powerful protest movement led by communists, Ankur is the first of Benegal’s rural reform trilogy comprising Nishant and Manthan, and the start of a prolific and consistently ambitious filmography. Through the 1970s, 1980s, 1990s, and 2000s, Benegal made feature films, documentaries and TV series regularly, marking himself out as one of the most productive filmmakers in India, alongside Satyajit Ray and Mrinal Sen. At 88 (as per Encyclopaedia Britannica, whose website is incidentally managed partly by Mrinal Sen’s son, Kunal Sen), Benegal is at present directing a biopic on Mujibur Rehman, and is arguably the oldest working filmmaker in India and even perhaps across the world.

So, this book comes at a timely moment to take stock of Benegal, the director. The book comprises essays on 15 of Benegal’s 21 feature films released so far (Charandas Chor, Kondura/Anugraham, Trikal, Susman, Sardari Begum, Samar, and Hari-Bhari are the ones left out). Each is a textual analysis of Benegal’s work—a reading of the plot of the film(s) seen through the lenses of politics and ideology. There is almost nil discussion on the technical aspects of Benegal’s work, barring passing mentions.

The unambiguous triumph of the book is the discussion on Benegal’s portrayal of women. This emerges seemingly organically: every essay notes the complexity and richness of Benegal’s female characters, who are presented not as projects whose lives must be improved, but as human beings who give in to temptation and make mistakes. A lot more has been made of Ray’s women or Rituparno Ghosh’s non-cis male characters. Benegal has never been considered in the same way for his women characters. All the essays consistently stress Benegal’s rich portrayal of women. This is true even of the so-called more political films like Ankur, Nishant, and Manthan, as well as of biopics like The Making of the Mahatma. The discussion on Benegal’s work on Kasturba Gandhi is particularly thoughtful.

The film-by-film treatment makes clear the other thread running through Benegal’s filmography—his long-time engagement with politics, beginning with Ankur to his somewhat more commercially packaged comedies in the 2000s, such as Well Done Abba. A couple of essays note that the film scholar Madhava Prasad has criticised Benegal for his Nehruvian, read statist, vision of politics, so this is not an uncritical appraisal. At the same time, one essay notes how Benegal worked with a storeyed writing team comprising celebrated playwrights Vijay Tendulkar, Satyadev Dubey (both in Marathi), Girish Karnad (in Kannada), and screenplay writer Shama Zaidi, who wrote Garm Hawa and Shatranj Ke Khiladi, among several other memorable films.

Lost opportunity

Calling a filmmaker political often does them injustice because they are seen as uninterested in storytelling and the inner lives of characters. Benegal’s stories contain memorable characters, complex and not merely shaped by the currents of politics and history.

Frontline for more