by BETH MOLE

It’s the first time the snake parasite has been seen in a human, let alone a brain

A neurosurgeon in Australia pulled a wriggling 3-inch roundworm from the brain of a 64-year-old woman last year—which was quite the surprise to the woman’s team of doctors and infectious disease experts, who had spent over a year trying to identify the cause of her recurring and varied symptoms.

A close study of the extracted worm made clear why the diagnosis was so hard to pin down: the roundworm was one known to infect snakes—specifically carpet pythons endemic to the area where the woman lived—as well as the pythons’ mammalian prey. The woman is thought to be the first reported human to ever have an infection with this snake-adapted worm, and it is the first time the worm has been found burrowing through a mammalian brain.

When the woman’s illness began, “trying to identify the microscopic larvae, which had never previously been identified as causing human infection, was a bit like trying to find a needle in a haystack,” Karina Kennedy, a professor at the Australian National University (ANU) Medical School and Director of Clinical Microbiology at Canberra Hospital, said in a press release.

The case, reported in the latest issue of Emerging Infectious Diseases, began in January 2021. The woman went to a local hospital in southeastern New South Wales, Australia, with a three-week history of abdominal pain, diarrhea, dry cough, and night sweats. Her blood work indicated an infection of some kind, and scans showed signs of pneumonia in her lungs as well as lesions in her spleen and liver. But tests for known microorganisms and parasites came up negative, as did tests for cancers and autoimmune disease. She was diagnosed with an unexplained case of pneumonia and given a corticosteroid, prednisolone.

Three weeks later, she was admitted to another hospital for recurrent fever and persistent cough. Again, doctors found the lung, liver, and spleen injuries as well as signs of an infection. Her blood had high levels of eosinophils, white blood cells known to fight off parasitic infections. They treated her for the high eosinophil levels and, out of concern there was a false-negative for a human roundworm infection, treated her with the anti-parasitic drug ivermectin.

From mid-2021 to early 2022, the woman’s liver and lungs improved. With the addition of another drug to help keep her eosinophil counts down, she was able to lower the dose of prednisolone.

Brain burrower

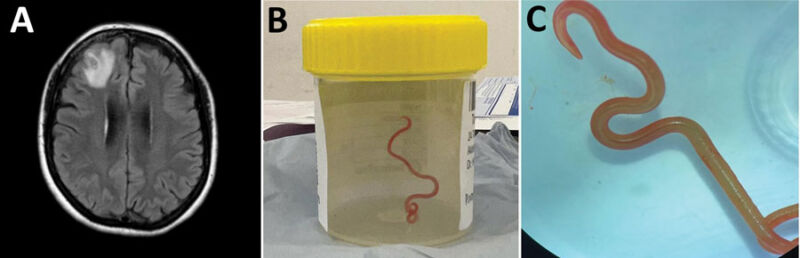

But, not long after that, she went through a three-month bout of forgetfulness and worsening depression. Brain magnetic resonance imaging found a growing lesion in her right frontal lobe. In June 2022, she went under the knife for a biopsy—and that’s when the neurosurgeon pulled out the live, writhing parasite from her brain.

Subsequent examination determined the roundworm was Ophidascaris robertsi based on its red color and morphological features. Genetic testing confirmed the identification.

The woman went on ivermectin again and another anti-parasitic drug, albendazole. Months later, her lung and liver lesions improved, and her neuropsychiatric symptoms persisted but were improved.

The doctors believe the woman became infected after foraging for warrigal greens (aka New Zealand spinach) around a lake near her home that was inhabited by carpet pythons. Usually, O. robertsi adults inhabit the snakes’ esophagus and stomach and release their eggs in the snakes’ feces. From there, the eggs are picked up by small mammals that the snakes feed upon. The larvae develop and establish in the small mammals, growing quite long despite the small size of the animals, and the worm’s life cycle is complete when the snake eats the infected prey.

Ars Technica for more