by B. JEYAMOHAN (translated from Tamil by Iswarya V.)

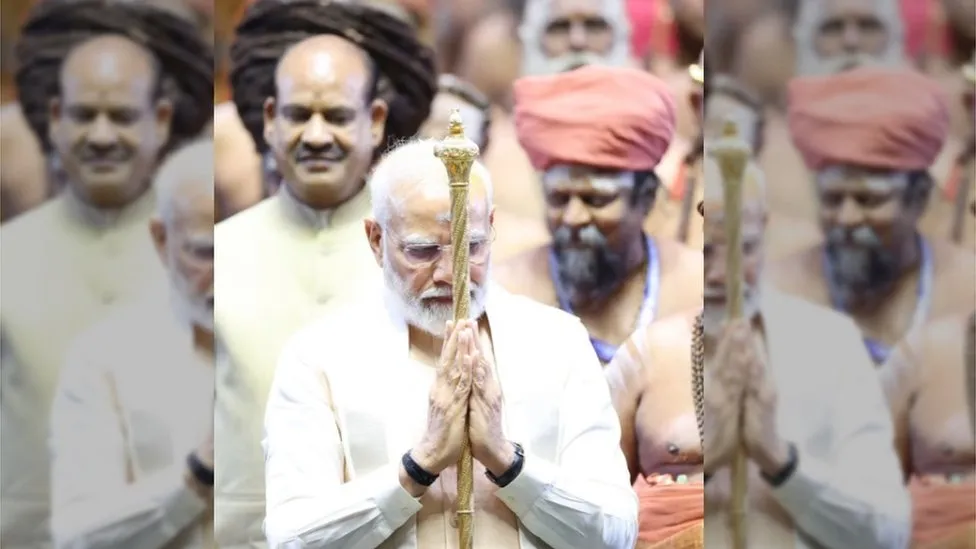

The “sengol” controversy brings the clash between divine authority and democratic ideals to the fore, challenging the very essence of governance.

At one of our philosophy training camps, I asked the young participants what they considered was a landmark in the realm of thought in the last few centuries. Was it the principle of equality, the concept of individualism, the idea of a welfare state, or a permissive cultural turn normalising hedonism? A discussion ensued, at the end of which I said, “All these are important, of course, but the seismic shift underlying all these is the move to divest authority of its claim to divine stature. This is the historic change that marked the end of an old world order and shaped the modern world as we see it today. It remains a promise and hope for all future. The ideas of human rights, equality, and the welfare state—they all turn on this singular pivot.”

The very thought—authority sans divinity—is novel to humankind and can outrage a traditional mind. I was born in Travancore 15 years after the long shadow of monarchy finally receded in 1947. But people like my father, who were born in the 1920s, were ardent royalists and fierce opponents of democracy. If someone told my father that the Travancore King was no different from common mortals, he would have had a fit of rage or broken down in tears. Several years later, when I met the then Maharaja of Travancore, I could not take a seat in front of him, even when he repeatedly pressed me to, because at the back of my mind I felt that my father, the late Sankarapillai Bahuleyan Pillai, would not have approved of it. Traditionalism, after all, still has a vicelike grip on us.

The association of monarchs with divinity is age-old across the world. All of India’s kings belonged to the Suryavamsa, Chandravamsa or Agnivamsa clans, claiming descent from the sun, moon, or fire gods, though born of human wombs. The King of Travancore was twice-born through a Vedic ritual called Hiranyagharba. As the priests chanted the Vedas, the king would descend into a golden trough filled with panchagavya—a mixture of five ingredients derived from the cow, namely dung, urine, milk, ghee and curd—only to emerge on the other side. Thus he symbolically entered the womb of the divine cow and was born again. The Maratha warrior Shivaji assumed the title of Chhatrapati only after the Brahmin priest Gaga Bhatta performed a similar ritual of holy ablution.

From sceptre to ballot, the evolution of power in India

In 1749, King Marthanda Varma of Travancore prostrated before the Ananta Padmanabha deity of Thiruvananthapuram with his royal sword, and went on to rule under the name Sri Padmanabha Dasan, the god’s servant. By this manoeuvre, he instantly transformed all rebel chieftains into godless sinners deserving of punishment; they were brutally killed, their womenfolk captured and sold. Once the king became god’s representative, even the cruelties he inflicted assumed divine sanction.

In 1948, the Travancore King’s divine authority was unceremoniously snatched away by an emissary of Vallabhbhai Patel, and Travancore became part of India. A new head of state was elected to power. People like my father could not stomach it. The new ruler Pattom A. Thanu Pillai was just another Pillai like my father! By what authority could he assume power?

Until the last century, it was widely believed that treason and blasphemy amounted to the same thing. Royal authority was tied to divinity through religion. The clergy accorded the king the seal of divine approval. In turn, the king established the clergy as direct representatives of god. Vedic Brahmins, Christian priests, Islamic clerics, and Buddhist monks were all empowered to designate the king as divine.

Resistance to this tradition of apotheosis came gradually, built by hundreds of philosophers, political thinkers, and writers, who shaped an alternative vision, often paying for such heresy with their lives. Beginning in 1215 with the Magna Carta in Britain, secularisation of authority—the idea that rulers have no special divine mandate—evolved over the centuries in Europe. It must be counted as one of the great miracles of the last century that India too adopted this foreign idea.

This miracle, I would say, was wrought by Gandhi. Dressed as a humble peasant, he embodied the idea that a leader may arise from anywhere; his very appearance symbolised it. Indians accepted the leadership of a half-naked fakir in the place of an emperor with crown and regalia, thereby ushering in the age of democracy.

India’s first democratic leaders were all defined by the same simplicity. Kamaraj used to casually walk down the road with his followers. E.M.S. Namboothiripad would go to the Secretariat on foot carrying his own bag. He asserted that Gandhi lived on in all of them. In a span of just 75 years, such leaders have become a lost tribe.

In the last century, all positions of power—from king to local village chieftain—were considered sacrosanct. The authority of the village headman in Tamil Nadu depended on the village priest giving him pride of place and a ceremonial headdress at the local temple festival. In Thoppil Mohammad Meeran’s novel Harbour, we see the authority of the Muslim leader manifest in his sitting at the head of the prayer gathering and sending his turban to the mosque on a platter.

This tradition of sanctification of authority did not, in fact, trickle down from the kings; rather, it grew bottom up from our cultural roots. Among the Travancore tribes like Paliyars and Kanikars, it is the priest who vests the chieftain with authority. The priest, who communicates directly with the deity and through whom oracular utterances are made, is himself often worshipped by tribesmen. The staff in such a priest’s hand becomes the foremost sign of authority. Until a hundred years ago, the priests of the Kanikar tribe never laid their staff down on any occasion. According to anthropologist Karasur Padmabharati, the nomadic Narikuravas carry their deity inside a cloth bundle, which must never touch the ground. Their leadership too draws authority from their deity.

Frontline for more