by THOMAS WHITESIDE

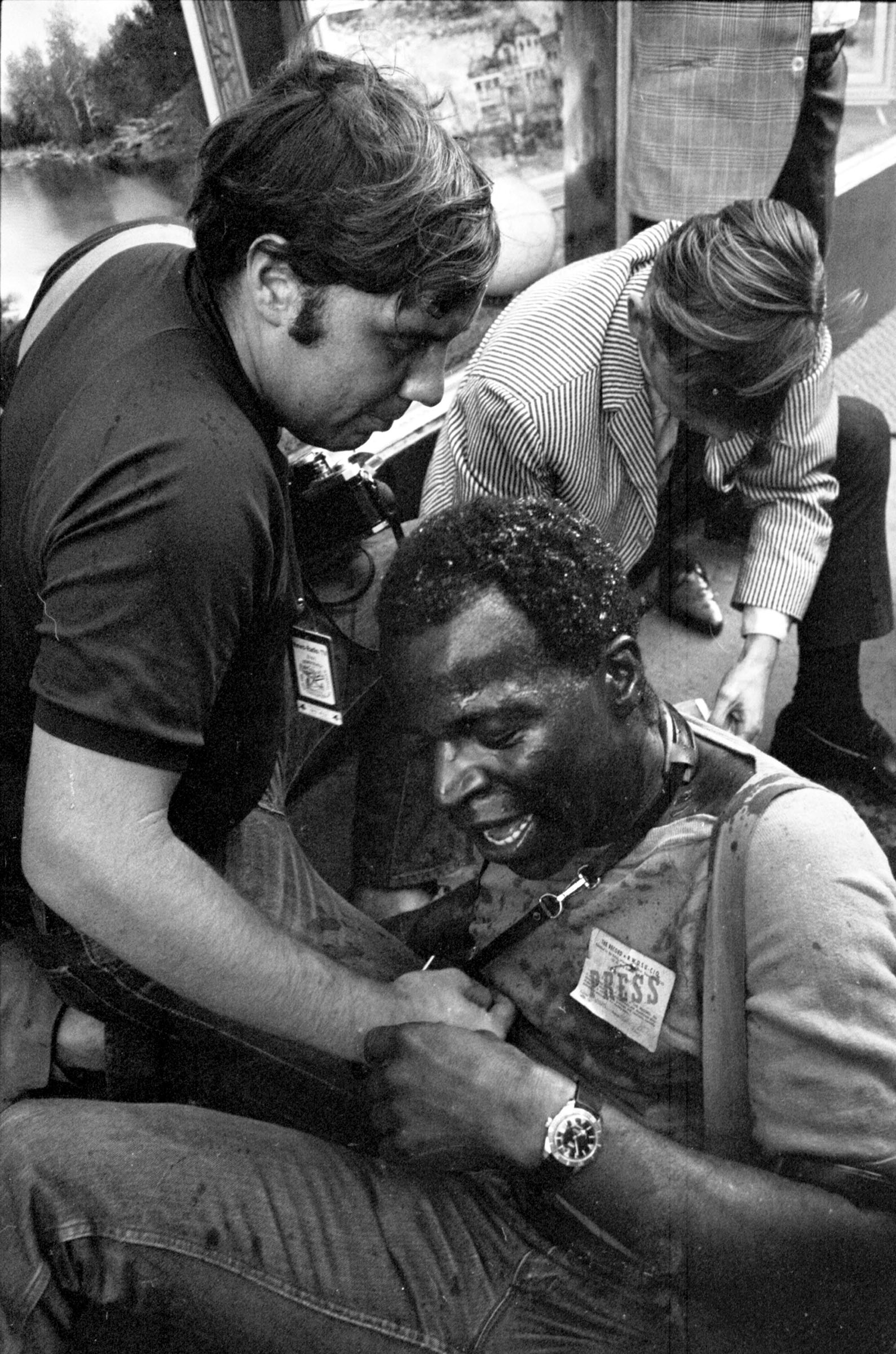

Context clues: The Democratic Convention in Chicago, in August 1968, was surrounded by protesters and made bloody by police violence. Whiteside, on the scene following along with CBS News, observed the coverage and the extent to which television could capture reality. His report appeared in the Winter 1968/69 issue.

On the afternoon of Wednesday, August 28, as the Democratic National Convention was called to order by Chairman Carl Albert on the floor of the International Amphitheatre in Chicago, I was sitting at the back of the Central Control Room of the Columbia Broadcasting System convention headquarters several hundred feet away, watching the proceedings on a bank of monitors and listening to the talk on the Central Control intercommunications system among the men who were in charge of various aspects of the CBS coverage. I was there to try to get some sense of the process of communication involved in the portrayal of a modern political convention by a great television network. As it happened, I was to get something else, too: a sense of the problems involved in the television coverage of a confrontation between the myrmidons of established political authority and modern political protestants.

Although the television editorial process embraces many stages of preparation and selection, for my purposes Central Control was the best place I could think of to take in both the final televised act itself and the flow of material contributing to it, and to obtain some feeling of the editorial judgment being exercised in the compilation of the stream of images that went out on the air to the tens of millions of people watching CBS on their home screens that day. Network coverage of political conventions is a massive logistical undertaking. For CBS in 1968, it involved the deployment, first to Miami Beach and then to Chicago, of some 800 people—engineers, camera crews, trouble-shooters and expediters of all kinds, news writers, directors and producers, and on-the-air correspondents and commentators—and of perhaps two hundred tons of very complex and expensive equipment, including huge self-contained trailer or mobile van units housing a staggering array of electronic gadgetry, office trailers, and control rooms, as well as mobile electronic camera units. In addition to transporting all this equipment to Chicago and arranging it in a cluster interconnected by a highly intricate wiring system, in a large warehouse-like area forming part of the International Amphitheatre building, CBS News had also erected, within the Amphitheatre itself, two fixed installations that overlooked the convention floor—its anchor booth for Walter Cronkite, the CBS anchor man, and a much smaller booth, very high up on one side of the Amphitheatre, from which the work of the CBS News correspondents on the convention floor could be directed. Also, just outside the convention floor, CBS had erected a large newsroom and another television studio, called the analysis studio, from which Eric Sevareid and Roger Mudd were to make periodical commentaries or to interview political figures.

Besides the Central Control Room, CBS had several other trailer control rooms into which television images flowed and in which editorial judgments were made. These included Perimeter Control, which received the output of cameras placed outside the entrances to the convention floor and from immediately outside the delegates’ entrance to the Amphitheatre building, and Remote Control, which, with another trailer control room called Videotape that was served by five videotape recording and storage vans, received the output of electronic and film camera crews at the Conrad Hilton Hotel—the headquarters for the Democratic National Committee—and the Blackstone Hotel in downtown Chicago, and from roving crews on assignment around the city. Because of a long-standing strike of telephone workers in Chicago that made impossible the installation of remote microwave transmission equipment in the city, live coverage of activities in Chicago concerning the convention was limited to the International Amphitheatre. Thus, whatever images were fed into CBS headquarters at the Amphitheatre from downtown arrived there in the form of videotape or film sent by courier to the Videotape Room, from which it could be fed to the Remote Control Room.

From all the control rooms through which such streams of images passed, after a preliminary editorial straining that might select, say, the output of two television cameras out of eight that were available, tributary streams then flowed into Central Control. There, from a large bank of monitors, the shots that actually were to go on the air could be finally selected. Physically, Central Control consisted of two huge trailers placed side by side, with one wall of each removed so as to produce a large unobstructed area, and this area was further increased by the addition of a fixed enclosure between the two open sides. The focal point of Central Control was the bank of monitoring screens I have referred to. There were five rows of screens and individual monitors identified by such titles as “CAM 1,” “CAM 2,” “REMOTE A,” “REMOTE B,” “PERIMETER A,” “PERIMETER B,” and so on. Before this bank of monitors were two long rows of consoles staffed by technicians and production people, including Vern Diamond, CBS News Senior Director; Gordon Manning, a CBS vice-president who is Director of News; and Robert Wussler, executive producer and director of the CBS News Special Events Unit. Wussler, who is in his early 30’s, is a round-faced man with a large forehead and rather prominent eyes. He has a controlled manner and a flow of energy that round-the-clock working habits seem in no way to diminish. It was essentially through Wussler’s marshaling of subject matter, usually minutes ahead of its actual appearance on the air, that the general pattern of the CBS coverage seemed to emerge. Wussler sat in the center of the second row of consoles, wearing a microphone-earphone headset, and in front of him he had an intercommunications box connecting him with each of the producers in the various sub-control rooms: Robert Chandler in Perimeter Control; Bill Crawford in Videotape; Casey Davidson and Sid Kaufman in Remote Control; Paul Greenberg in Floor Control, a small booth high up in the Amphitheatre from which the work of the CBS floor correspondents was guided; Sanford Socolow, the producer attached to the anchor booth; and Jeff Gralnick, an associate producer who sat next to and was the immediate liaison with Walter Cronkite, the anchor man, or, as he was sometimes simply referred to on the intercom, “the Star.” Through an extra earphone I was able, while sitting in Central Control and watching the bank of monitors, to hear Wussler’s conversations over the intercommunications system with all his producers, as well as with Diamond, who had responsibility not only for the direction of cameras on the convention floor but also for the exacting job of choosing, from among the bank of monitors, shots that actually went on the air. That Wednesday I was able to see and hear how, in this nerve center, CBS News went about the business of informing its audience on subjects that included the debate on the issue of that part of the Administration-backed platform dealing with the war in Viet Nam, and also, later on that evening, the violence that was to erupt between police and anti-war demonstrators, and other events in downtown Chicago.

Columbia Journalism Review for more