by TARIQ ALI

In 1968, fury at the Vietnam war sparked protests and uprisings across the world: from Paris and Prague to Mexico. Tariq Ali considers the legacy 40 years on

A storm swept the world in 1968. It started in Vietnam, then blew across Asia, crossing the sea and the mountains to Europe and beyond. A brutal war waged by the US against a poor south-east Asian country was seen every night on television. The cumulative impact of watching the bombs drop, villages on fire and a country being doused with napalm and Agent Orange triggered a wave of global revolts not seen on such a scale before or since.

If the Vietnamese were defeating the world’s most powerful state, surely we, too, could defeat our own rulers: that was the dominant mood among the more radical of the 60s generation.

In February 1968, the Vietnamese communists launched their famous Tet offensive, attacking US troops in every major South Vietnamese city. The grand finale was the sight of Vietnamese guerrillas occupying the US embassy in Saigon (Ho Chi Minh City) and raising their flag from its roof. It was undoubtedly a suicide mission, but incredibly courageous. The impact was immediate. For the first time a majority of US citizens realised that the war was unwinnable. The poorer among them brought Vietnam home that same summer in a revolt against poverty and discrimination as black ghettoes exploded in every major US city, with returned black GIs playing a prominent part.

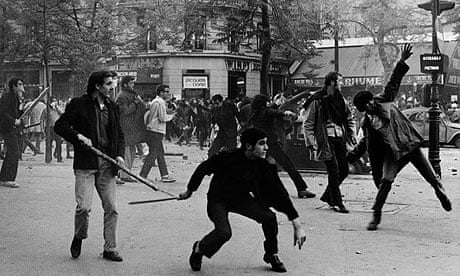

The single spark set the world alight. In March 1968, students at Nanterre University in France came out on to the streets and the 22 March Movement was born, with two Daniels (Cohn-Bendit and Bensaid, Nanterre students then, and both still involved in green or leftist politics) challenging the French lion: Charles de Gaulle, the aloof, monarchical president of the Fifth Republic who, in a puerile outburst, would later describe as chie-en-lit – “shit in the bed” – the events in France that came close to toppling him. The students began by demanding university reforms and moved on to revolution.

That same month in London, a demonstration against the Vietnam war marched to the US embassy in Grosvenor Square. It turned violent. Like the Vietnamese, we wanted to occupy the embassy, but mounted police were deployed to protect the citadel. Clashes occurred and the US senator Eugene McCarthy watching the images demanded an end to a war that had led, among other things, to “our embassy in Europe’s friendliest capital” being constantly besieged. Compared with the ferment elsewhere, Britain was a sideshow (“…in sleepy London Town there’s just no place for a street fighting man,” Mick Jagger sang later that year): university occupations and riots in Grosvenor Square did not pose any real threat to the Labour government, which backed the US but refused to send troops to Vietnam.

In France, the existentialist philosopher Jean-Paul Sartre was at the peak of his influence. Contrary to Stalinist apologists, he argued that there was no reason to prepare for happiness tomorrow at the price of injustice, oppression or misery today. What was required was improvement now.

By May, the Nanterre students’ uprising had spread to Paris and to the trade unions. We were preparing the first issue of The Black Dwarf as the French capital erupted on May 10. Jean-Jacques Lebel, our teargassed Paris correspondent, was ringing in reports every few hours. He told us: “A well-known French football commentator is sent to the Latin Quarter to cover the night’s events and reported, ‘Now the CRS [riot police] are charging, they’re storming the barricade – oh my God! There’s a battle raging. The students are counter-attacking, you can hear the noise – the CRS are retreating. Now they’re regrouping, getting ready to charge again. The inhabitants are throwing things from their windows at the CRS – oh! The police are retaliating, shooting grenades into the windows of apartments…’ The producer interrupts: ‘This can’t be true, the CRS don’t do things like that!’

” ‘I’m telling you what I’m seeing…’ His voice goes dead. They have cut him off.”

The police failed to take back the Latin Quarter, now renamed the Heroic Vietnam Quarter. Three days later a million people occupied the streets of Paris, demanding an end to the rottenness of the state and plastering the walls with slogans: “Defend The Collective Imagination”, “Beneath The Cobble- stones The Beach”, “Commodities Are The Opium Of The People, Revolution Is The Ecstasy Of History”.

Eric Hobsbawm wrote in The Black Dwarf: “What France proves is when someone demonstrates that people are not powerless, they may begin to act again.”

I had been planning to head for Paris – it was something we had been discussing at the paper – but then I received a late-night phone call. A posh voice said, “You don’t know who I am, but do not leave the country till your five years here are up. They won’t let you back.” In those days, citizenship for Commonwealth citizens was automatic after five years. I would not complete my five years until October 1968. Already Labour cabinet ministers had been discussing in public whether or not I could be deported. Friendly lawyers confirmed I should not leave the country. Clive Goodwin, the publisher of our mag, vetoed the trip and went off himself.

I went a year later to help Alain Krivine, one of the leaders of the May 1968 revolt, in his presidential campaign, standing for the Ligue Communiste Révolutionnaire. As we touched down at Orly airport, returning from a rally in Toulouse, the French police surrounded the plane. “Hope it’s you, not me,” muttered Krivine. It was. I was served an order banning me from France which stayed in force until François Mitterand’s election many years later.

The Guardian for more