by LAEXANDER POOTS

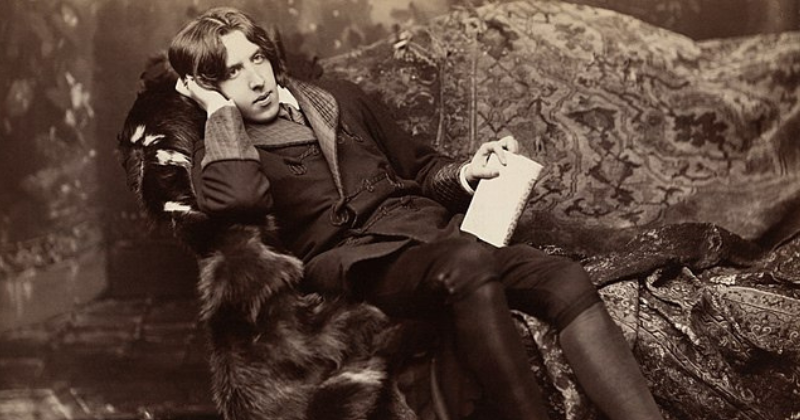

When still a boy, Forrest Reid saw Oscar Wilde in Belfast.

I beheld my ?rst celebrity. Not that I knew him to be celebrated, but I could see for myself his appearance was remarkable. I had been taught that it was rude to stare, but on this occasion, though I was with my mother, I could not help staring, and even feeling I was intended to do so. He was, my mother told me, a Mr. Oscar Wilde.

Reid presents his boyhood sighting of the famous writer as little more than a curious anecdote. He was 20 years old in 1895, the year of the Wilde Affair. In early April of that year, the newspapers were full of Wilde’s lawsuit against the Marquess of Queensberry. Just a few weeks later, the papers were full of Wilde’s fall from grace. He became a byword for infamy in England and Ireland. Worst of all, his very name became a slur.

Reid lived through it all. The man he had seen promenading through Belfast was now circling a prison yard. How did they make him feel, those broadsheets at the breakfast table? Perhaps they frightened him. An unwelcome premonition of his own future. Desire reduced to commerce, letters sent and regretted, a life spent waiting for the blackmailer’s note or the policeman’s knock. And yet even then Reid must have known that his life, queer fellow though he was, would not take that shape. Wilde’s passions were shallower than Reid’s, and much more dangerous.

The taint associated with Wilde’s name outlived him by decades. Seventeen years after Wilde’s death, C. S. Lewis told Arthur Greeves that he was happy to discuss male beauty, as long as they avoided “everything that tends to sordidness (and beastly police court sort of scandal out of grim real life, like the O. Wilde story).” It was Wilde’s tragedy that his care fully curated persona should come to be synonymous with “grim real life.” Even E. M. Forster kept him at arm’s length. In Maurice, the eponymous character confesses to his doctor that he is “an unspeakable of the Oscar Wilde sort.”

Fifty-four years after Wilde’s death, Brian O’Nolan, a Tyrone man fond of pseudonyms, who wrote novels as Flann O’Brien and a weekly column for the Irish Times as Myles na Gopaleen, railed against a proposed memorial in Dublin: “Oscar Wilde was not an Irishman, except by statistical accident of birthplace. He had become completely déraciné and living in England before he was 20. Not one shred of his literary work even suggests an Irish inflection.” Oscar’s shame could not be allowed to reflect on Ireland.

Wilde’s connection to the North of Ireland is little known. The fact that Wilde was Irish at all is news to some people. Born in Dublin in 1854, Wilde spent his earliest years at 21 Westland Row and 1 Merrion Square. After seven years of boarding school in County Fermanagh, he returned to Dublin for a degree at Trinity College. He did not leave for England until he was 20 years old—still young, but then he would be dead at the age of 46. Nearly half of his short life was lived in Ireland. And yet Oscar’s Irishness can still surprise. In 1998, Jerusha McCormack, then a lecturer at University College Dublin, noted her “frustration at having to explain to Irish students that Oscar Wilde was, yes, indeed, Irish.”

Literary Hub for more