by SCOTT ALEXANDER

I.

An academic once asked me if I was writing a book. I said no, I was able to communicate just fine by blogging. He looked at me like I was a moron, and explained that writing a book isn’t about communicating ideas. Writing a book is an excuse to have a public relations campaign.

If you write a book, you can hire a publicist. They can pitch you to talk shows as So-And-So, Author Of An Upcoming Book. Or to journalists looking for news: “How about reporting on how this guy just published a book?” They can make your book’s title trend on Twitter. Fancy people will start talking about you at parties. Ted will ask you to give one of his talks. Senators will invite you to testify before Congress. The book itself can be lorem ipsum text for all anybody cares. It is a ritual object used to power a media blitz that burns a paragraph or so of text into the collective consciousness.

If the point of publishing a book is to have a public relations campaign, Will MacAskill is the greatest English writer since Shakespeare. He and his book What We Owe The Future have recently been featured in the New Yorker, New York Times, Vox, NPR, BBC, The Atlantic, Wired, and Boston Review. He’s been interviewed by Sam Harris, Ezra Klein, Tim Ferriss, Dwarkesh Patel, and Tyler Cowen. Tweeted about by Elon Musk, Andrew Yang, and Matt Yglesias. The publicity spike is no mystery: the effective altruist movement is well-funded and well-organized, they decided to burn “long-termism” into the collective consciousness, and they sure succeeded.

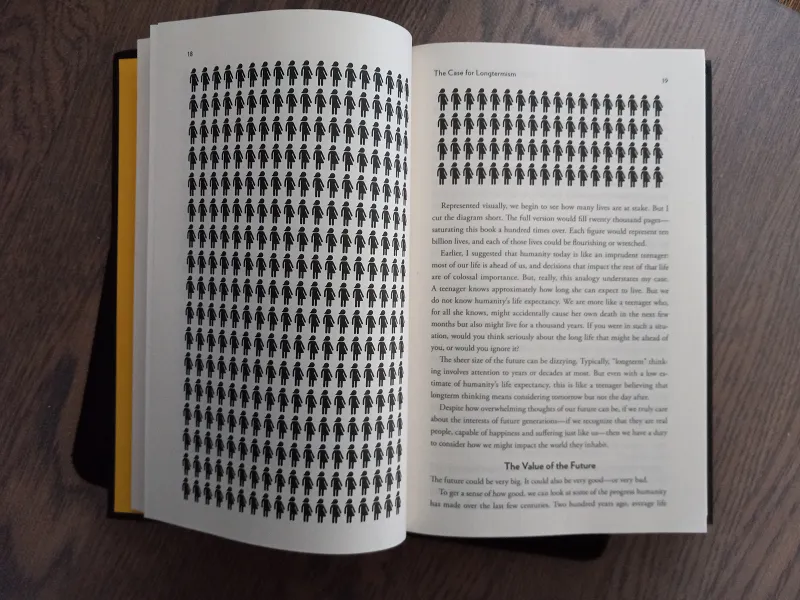

But what is “long-termism”? I’m unusually well-placed to answer that, because a few days ago a copy of What We Owe The Future showed up on my doorstep. I was briefly puzzled before remembering that some PR strategies hinge on a book having lots of pre-orders, so effective altruist leadership asked everyone to pre-order the book back in March, so I did. Like the book as a whole, my physical copy was a byproduct of the marketing campaign. Still, I had a perverse urge to check if it really was just lorem ipsum text, one thing led to another, and I ended up reading it. I am pleased to say that it is actual words and sentences and not just filler (aside from pages 15 through 19, which are just a glyph of a human figure copy-pasted nine hundred fifty four times)

So fine. At the risk of joining on an already-overcrowded bandwagon, let’s see what we owe the future.

II.

All utilitarian philosophers have one thing in common: hypothetical scenarios about bodily harm to children.

The effective altruist movement started with Peter Singer’s Drowning Child scenario: suppose while walking to work you see a child drowning in the river. You are a good swimmer and could easily save them. But the muddy water would ruin your expensive suit. Do you have an obligation to jump in and help? If yes, it sounds like you think you have a moral obligation to save a child’s life even if it costs you money. But giving money to charity could save the life of a child in the developing world. So maybe you should donate to charity instead of buying fancy things in the first place.

Astral Codex Ten for more