by MATTHEW WARREN

Ancestry revealed

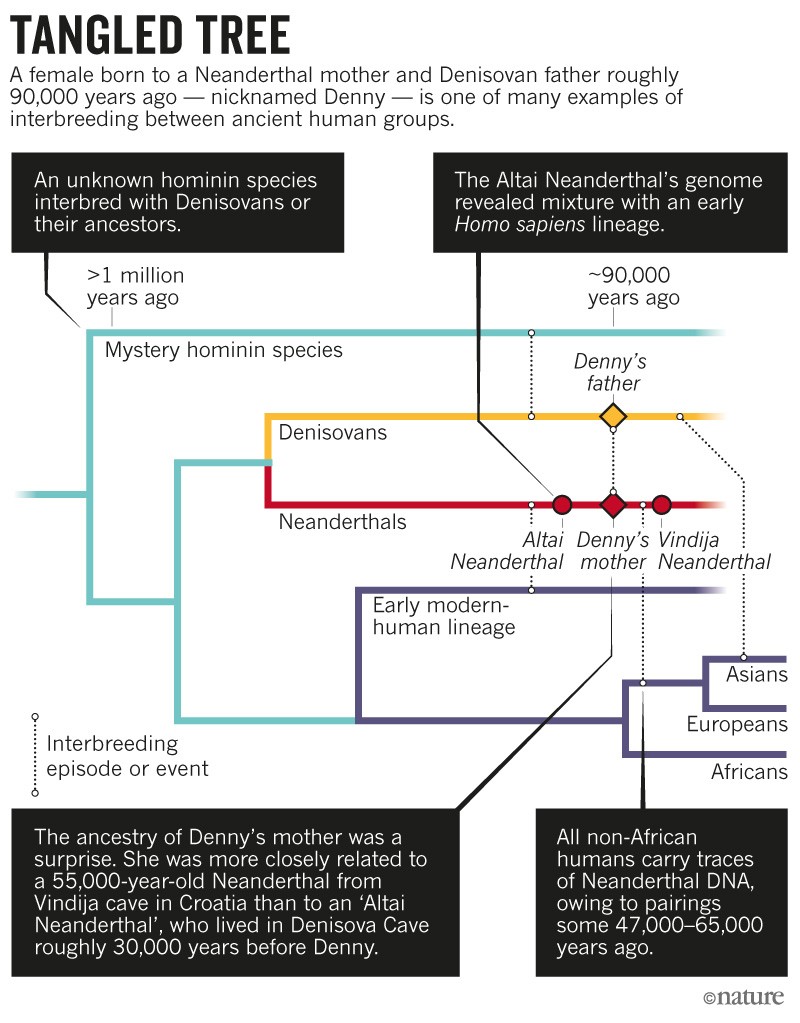

Pääbo’s team first uncovered Denny’s remains several years ago, by looking through a collection of more than 2,000 unidentified bone fragments for signs of human proteins. In a 2016 paper4, they used radiocarbon dating to determine that the bone belonged to a hominin who lived more than 50,000 years ago (the upper limit of the dating technique; subsequent genetic analysis has put the specimen at around 90,000 years old, according to Pääbo). They then sequenced the specimen’s mitochondrial DNA — the DNA found inside cells’ energy converters — and compared that data to sequences from other ancient humans. This analysis showed that the specimen’s mitochondrial DNA came from a Neanderthal.

But this was only half of the picture. Mitochondrial DNA is inherited from the mother and represents just a single line of inheritance, leaving the identity of the father and the individual’s broader ancestry unknown.

In the latest study, the team sought to get a clearer understanding of the specimen’s ancestry by sequencing its genome and comparing the variation in its DNA to that of three other hominins — a Neanderthal and a Denisovan, both found in Denisova Cave, and a modern-day human from Africa. Around 40% of DNA fragments from the specimen matched Neanderthal DNA — but another 40% matched the Denisovan. By sequencing the sex chromosomes, the researchers also determined that the fragment came from a female, and the thickness of the bone suggested she was at least 13 years old.

With equal amounts of Denisovan and Neanderthal DNA, the specimen seemed to have one parent from each hominin group. But there was another possibility: Denny’s parents could have belonged to a population of Denisovan–Neanderthal hybrids.

A fascinating genome

To work out which of these options was more likely, the researchers examined sites in the genome where Neanderthal and Denisovan genetics differ. At each of these locations, they compared fragments of Denny’s DNA to the genomes of the two ancient hominins. In more than 40% of cases, one of the DNA fragments matched the Neanderthal genome, whereas the other matched that of a Denisovan, suggesting that she had acquired one set of chromosomes from a Neanderthal and the other from a Denisovan. That made it clear that Denny was the direct offspring of two distinct humans, says Pääbo. “We’d almost caught these people in the act.”

The results convincingly demonstrate that the specimen is indeed a first-generation hybrid, says Kelley Harris, a population geneticist at the University of Washington in Seattle who has studied hybridization between early humans and Neanderthals. Skoglund agrees: “It’s a really clear-cut case,” he says. “I think it’s going to go into the textbooks right away.”

Harris says that sexual encounters between Neanderthals and Denisovans might have been quite common. “The number of pure Denisovan bones that have been found I can count on one hand,” she says — so the fact that a hybrid has already been discovered suggests that such offspring could have been widespread. This raises another interesting question: if Neanderthals and Denisovans mated frequently, why did the two hominin populations remain genetically distinct for several hundred-thousand years? Harris suggests that Neanderthal–Denisovan offspring could have been infertile or otherwise biologically unfit, preventing the two species from merging.

Nature for nore