by RAHMANE IDRISSA

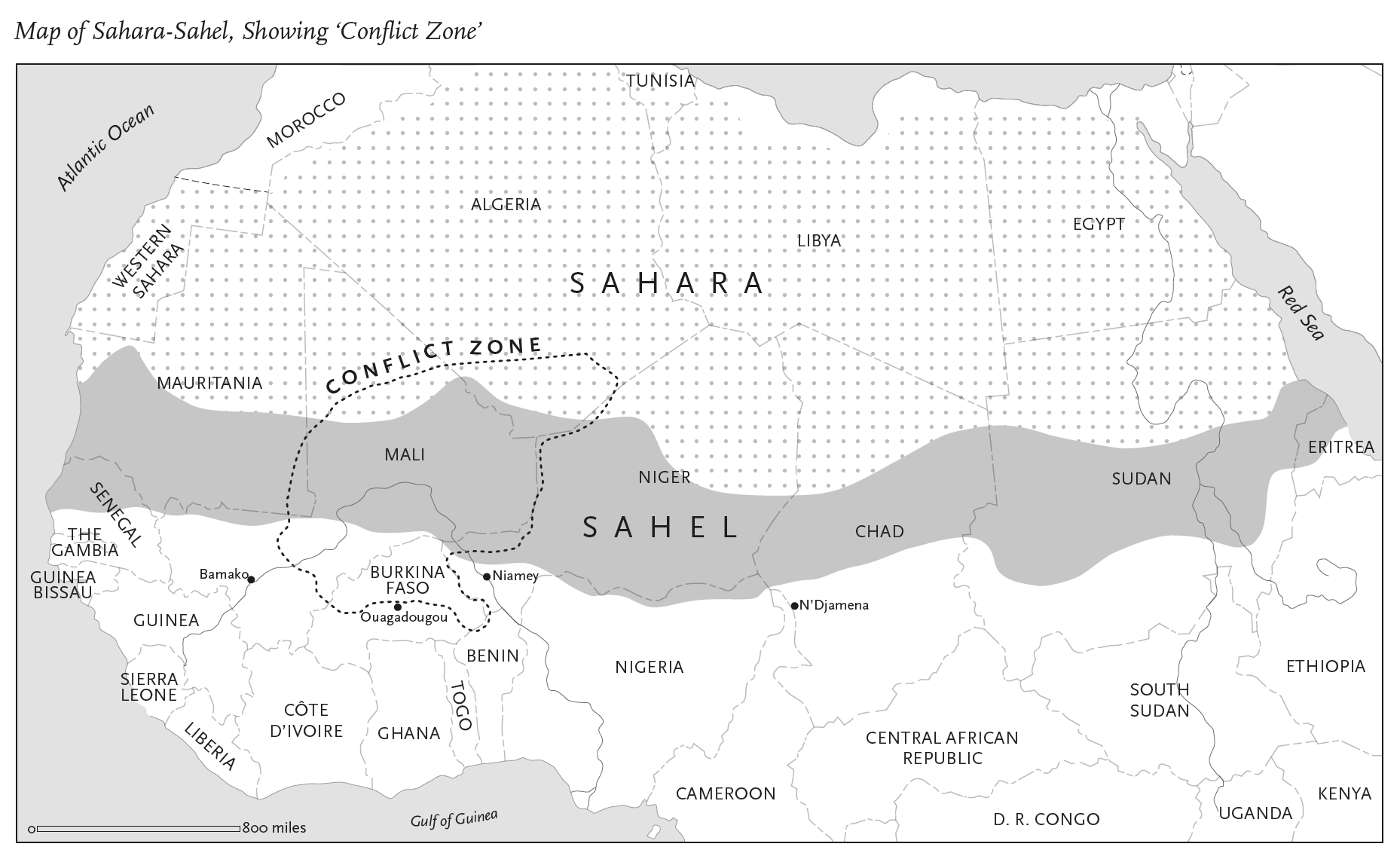

A feature of the Western ‘war on terror’ that seems to come out of fable rather than reality is an inability to see the enemy. In fact, it is an inability to define the enemy. In the Sahel, the French state has settled on ‘Islamist terrorists’, a sequence of adjectives that denote elusive subjects surging out of horizons of pure violence. The inability is compounded by the fact that terrorists must be picked out in terrains unknowable to the West, because the West has long considered them—still considers them—to be outside of history: Afghanistan, a redoubt against empires, those makers of history; the Sahel, a land somewhere in the continent that Hegel banished from history.

The name ‘Sahel’ speaks of nature rather than history. If capitalism is the driving force of modern history, students of the Sahel habitually describe it as the place where capitalism met its nemesis: intractable natural duress, and the weight of a culture so immobile that it is indistinguishable from nature and does not seem prone to melting into air. The Sahel traumatized Finn Fuglestad, a Norwegian historian who went to Niger in the late 1960s to write the history of a new African nation-state for his dissertation and came out of it convinced that Africans can never be part of the modern story of progress via Wille zur Macht over nature and matter. It was during these years that the terrible nature of the Sahel was brought home to bourgeois audiences in the West. One of the cyclical killer droughts of the region broke out in the early 1970s, a time when the mass media were beginning to have access to disasters in the Third World, and the Sahel entered Western chatter as a byword for drought, hunger, severe poverty and also—the contradiction does not strike—rapid demographic growth. Since from a Western bourgeois standpoint there is no obvious agential rationality in having so many children in such depleted circumstances, Sahelian demography must be as much a blind and inexorable force of nature as Sahelian drought. Bernard Lugan, a far-right historian who is the chosen interpreter of Africa for the French Army, calls it ‘suicidal’.footnote1

Menace to the West?

Before insurrectionary Salafism, what unnerved the West about the Sahel was demography. At an Élysée press conference in 2004, Chirac musingly relayed his personal impressions of a tour of Mali and Niger the previous year:

The key memories that stay with me are about the traditions of hospitality that the Africans have preserved and that I saw on the journey from the airport to the city centre. There was an immense crowd of youths who were, I would say, between five and fifteen, who were handsome, happy because something was happening, so they were chanting or dancing, they had clear warm eyes. And I was thinking, in just a few years, there will be a billion people in Africa, there will be 800 million youths . . . This is a ticking time-bomb.footnote2

This response to sighting multitudes of children and teenagers on the sun-blasted streets of Sahelian towns is common among Western visitors, and the ticking time-bomb metaphor is de rigueur for the Western commentariat. But in 2012, with the outbreak of war in Mali, the conventional threat of the population bomb graduated into an existential threat—to the liberal West—when violent Salafism appeared to blend into it. In 2015 Serge Michailof, a leading voice in the world of development aid, published a book menacingly titled Africanistan: Development or Jihad. The original French subtitle—‘Is a Crisis-ridden Africa Going to End up in Our Banlieues?’—points to another threat: mass migration to France and Europe, once the population bomb has exploded in a decade or two.

The Sahel of Michailof and other Western experts epitomizes the trifecta of alien demographic vitality, Islamic fanaticism and pauper migration that is the new spectre haunting the West. A 2017 briefing note from the Tony Blair Institute for Global Change stressed that ‘the Sahel has the capacity to be a massive disruptive force’ for the wider world.footnote3 Its very miseries apparently make the region a strategic menace of nearly Chinese or Russian proportions for the West, and first and foremost for Europe.footnote4 Unlike parts of Africa that have long been mired in immense tragedies—the Democratic Republic of Congo comes to mind—the Sahel requires urgent intervention because of its potential impact on metropolitan centres.

New Left Review for more