by LUCIANA BRITO (translated by JOYCE SILVA FERNANDES)

Black people make up the majority in Brazil. Over half of the nation’s 215 million inhabitants—56 percent or about 120 million people—are Afro-Brazilian, making the country home to the largest Black population in the Americas. As a result, analysis of all political, economic, societal, and cultural matters in Brazil must consider racial issues—or rather, issues of racial inequality—as a central axis.

For generations, a consensus reigned in both the academy and public opinion that Brazil’s leading problem was the problem of class inequality. The Right and the Left shared this perspective, refusing to recognize and confront racial inequities. The myth of racial democracy—the national narrative of harmony between races and the idea that racial mixing offered prime evidence of the absence of racial hostilities—served to defend these beliefs.

However, from the 1990s onwards, new studies seeking evidence-based understandings of race relations in Brazil began to question the thesis of a country, always positioned in contrast with the United States, where harmonious and egalitarian race relations flourished. Images deployed to promote tourism abroad featured smiling Afro-Brazilians having fun—caricatures that presented a carnivalesque representation of a country whose underlying inequalities could not be understood without analyzing and comparing the lives of Blacks and whites.

Indeed, in the social imagination and across the spheres of health care, politics, employment, and, above all, education and housing, two distinct Brazils are observable. One is a country of privileged people, while the other is a country of people whose lives are marked by poverty, the absence of multiple rights, and personal experiences of violent and traumatic events motivated by racial hatred.

For Black people, the data emerging from research in the 1990s and 2000s did not reveal anything new. Black social movements and popular organizations, many of them led by women, and Black workers’ collectives had been denouncing racism as the leading cause of the country’s racial inequities since the late 1960s and 1970s, then in a context of military dictatorship. With a critique of fictitious racial democracy, the Black movement interpreted the Black population’s life conditions as a consequence of the lack of a politics of inclusion and guarantees of citizenship, which remained absent after Brazil finally abolished slavery on May 13, 1888.

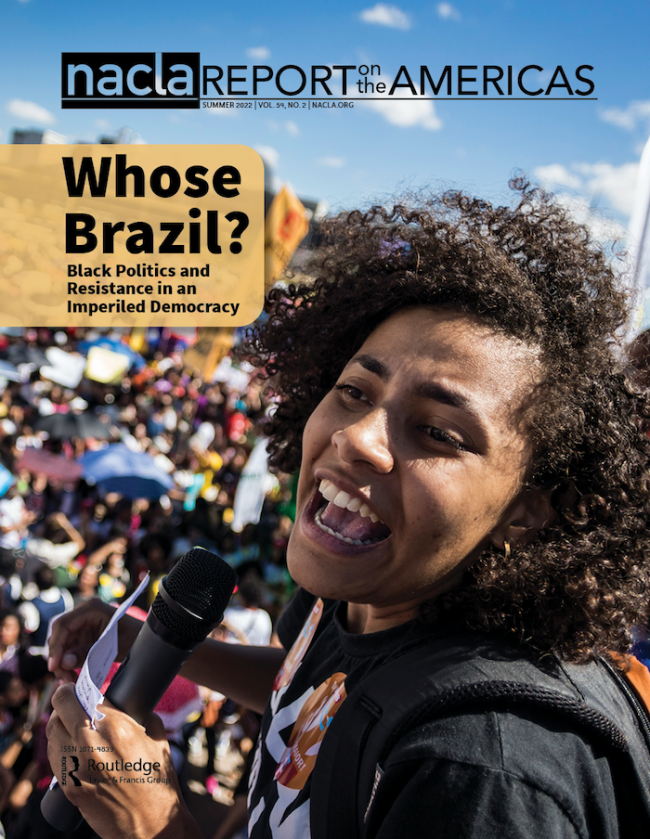

The photograph included here highlights an important moment for Black movements within the broader context of left-wing struggles in Brazil. In it, a group of Black adults and children dressed in red, a color associated with leftist social movements, march in the city of Salvador, the largest Black city in the Americas. It is a demonstration of the Landless Workers’ Movement (MST) around the year 2002. As they walk, boys look back innocently, as if signaling what the future will bring for those who fight for their rights. The backs of their shirts read: “Order means no one going hungry.”