by ROBERTO SIRVENT

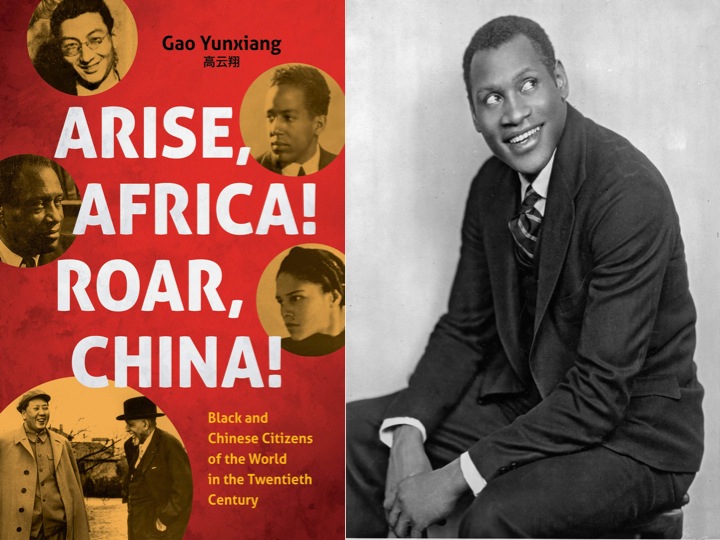

In this series, we ask acclaimed authors to answer five questions about their book. This week’s featured author is Gao Yunxiang . Gao Yunxiang is Professor of History at Ryerson University. Her book is Arise, Africa! Roar, China!: Black and Chinese Citizens of the World in the Twentieth Century.

Roberto Sirvent: How can your book help BAR readers understand the current political and social climate?

Gao Yunxiang: These five figures covered in Arise, Africa! Roar, China!: Black and Chinese Citizens of the World—W. E. B. Du Bois, Paul Robeson, Liu Liangmo, Sylvia Si-lan Chen, and Langston Hughes—enjoyed general friendship based on racial solidarity and shared anti-racism and anti-colonialism political activism. They interacted with one another in a variety of ways, at times collaborating and contributing to historic alliances, at other times falling in and out of love. The paths of the five figures frequently crossed at various venues supporting China’s resistance against Japan, the civil rights of African and Chinese Americans, and Anti-McCarthyism and supporting China in the Korean War. Together, the lives of these five citizens of the world stand as powerful counter to conventional narratives that foreground racism and alienation, offering a view into the power and potential of Black internationalism and Sino–African American collaboration. “Arise, Africa!” and “Roar, China!” as articulated by Du Bois and Hughes, respectively, match the shared struggles of a nation and a nation-within-a-nation. Their power and promise resonate to this day. Despite some tensions between the Chinese and African American communities, as manifested in attacks of Asian Americans by people of color and disagreement over such issues as public school and policing, fruitful collaboration between the Black Lives Matter and Stop Asian Hate movements to reduce racial violence and discrimination, are feasible.

What do you hope activists and community organizers will take away from reading your book?

These five citizens of the world had to constantly juggle the treacherously slippery and murky transpacific ideological and political landscapes entailed by their races and leftist activism with devotion, courage, and caution. Their lives and political activism were marked by narratives of survival. Readers will find that the political agility, linguistic skills, and affability that Liu Liangmo demonstrated in negotiating such obstacles particularly inspiring. Caught between the rivalries between the Nationalist and Communist forces while promoting mass singing songs of resistance against Japan, Liu migrated to the United States. After an illustrious career promoting China among Americans in the 1940s, he slipped back to China, beyond the clutches of the FBI and INS. Inventing and flexibly employing diverse tools such as mass singing, accessible print and photo journalism, and lecture tours, in both English and Chinese, Liu was able to mobilize and organize the grassroot masses and reach out to the elite across racial and national boundaries. Through collaboration with Paul Robeson and the Chinese People’s Chorus that he had organized among young employees of printing shops, restaurants, and members of the Chinese Hand Laundry Alliance in New York City’s Chinatown, Liu helped to popularize March of the Volunteers, the future national anthem of the People’s Republic of China, across the globe. That testified the power of Liu’s techniques and attitude of “do it” and “do it well” as an activist and organizer. In the People’s Republic of China, Liu managed to balance his Christianity with influence at the highest levels of the government and survive decades of social and political upheaval.

We know readers will learn a lot from your book, but what do you hope readers will un-learn? In other words, is there a particular ideology you’re hoping to dismantle?

While most scholarship on Sino-American relations treats the United States as default white, Arise, Africa! Roar, China! breaks new pathways by foregrounding African Americans, combining the study of Black internationalism and the experiences of Chinese Americans with a transpacific narrative, and understanding the global remaking of China’s modern popular culture and politics. I would like my readers reimagine Sino-American relations and China’s place in the world, by decentering Henry Kissinger and Richard Nixon in the narrative and by focusing on global anti-imperialism and popular movements, which are still relevant today. That would enable the understanding that Afro-Asian history is central to world history.

Who are the intellectual heroes that inspire your work?

How the five figures in this book overcome formidable obstacles with commitment are profoundly inspiring. Du Bois, Robeson, and Hughes were major American talents during the long Jim Crow era when their careers and lives were always vulnerable to racist discrimination and deadly violence. Liu and Chen navigated incessant political and social upheavals and wars. Yet, the tragic story of Paul Robeson is most inspiring to me. Enormously talented, passionate, committed, and politically innocent, he soared to great heights as a popular artistic hero but fell from international prominence into an eventual mental breakdown, paying the ultimate price for his unyielding pursuit of political and racial justice. The five figures’ political and cultural legacies persist in spite of the dramatic changes that followed their deaths. For instance, since 2009, the Ministry of Education of China has included a translation of “The Negro Speaks of Rivers” in the approved textbook of Chinese language and literature mandated for ninth graders across the nation to learn about the “condensed history of the Black race.” Hughes’s work thus continues to boast an enormous readership in China comparable only to that enjoyed by figures as prominent as Mao Zedong.

In what way does your book help us imagine new worlds?

Black Agenda Report for more