How a Khoja Family Helped Wire the Empire: The Chinoys and the Making of Cosmopolitan Capitalism

by DANISH KHAN

Bombay’s Chinoy family pioneered India’s international wireless communication and shaped cosmopolitan capitalism in the colonial era.

In the crowded economic history of colonial India, the spotlight is often trained on a familiar cast: the Parsis of Bombay – Tatas, Wadias, Godrejs; the Marwari financial giants of Calcutta like the Birlas; and Hindu industrial houses. These communities unquestionably shaped the contours of Indian capitalism. Yet this focus obscures the contributions of other groups who played pivotal roles in connecting India to global circuits of technology, finance and communication.

One such story is that of the Chinoys, a Khoja Ismaili Muslim business family from Bombay. Their rise from the China trade to the helm of India’s international wireless communication network illuminates a distinctive moment in India’s economic history – one in which indigenous capital, imperial technological ambition and flexible, cross-community partnerships came together to produce what we may call cosmopolitan capitalism.

This story not only unsettles the notion that Gujarati Muslim traders were confined to Indian Ocean commerce; it shows how local entrepreneurial families could position themselves at the centre of the empire’s most advanced technological systems.

The Chinoys: a family emerges

Like many Bombay merchant families, the Chinoys began in maritime trade. Their patriarch, Meherally Chinoy, started in the mid-nineteenth century as an apprentice to the Khoja merchant prince Jairazbhoy Peerbhoy. Through repeated voyages to China and Japan, he built a reputation for commercial acumen and established both capital and credibility. His sons consolidated and expanded this base.

The Wire for more

Partners in Empire: Indigenous business, imperial technology, and the Indian Radio Telegraph Company

by DANISH KHAN

Abstract

This article examines the introduction of the beam wireless system to India as part of the Imperial Wireless Chain, which enhanced communication links between Britain and India. It attributes the pioneering role in establishing the beam wireless service and laying the foundation for commercial radio broadcasting to a Bombay-based Ismaili Khoja family—the Chinoys—who secured necessary patents from Marconi and established the Indian Radio & Telegraph Company (IRTC). Departing from prevailing scholarship that frames Gujarati Muslim trading communities of Khojas, Bohras, Memons and groups such as Sindhis and Chettiars primarily as migrant transnational merchants (unlike Marwaris and Jains), this study foregrounds their role in a strategic, technology-driven infrastructure sector. It traces how the IRTC, born from colonial Bombay, created an unprecedented alliance of Parsi, Hindu and Muslim capital, exemplifying the city’s distinctive model of cosmopolitan capitalism.

Introduction

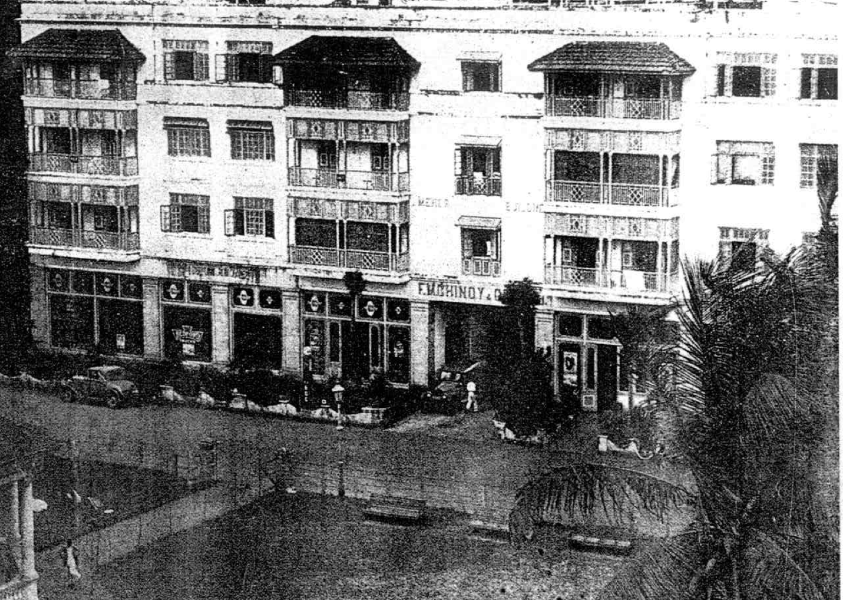

In colonial India, Bombay was an important centre of trade and finance. Unlike the other two Presidency towns of Calcutta and Madras, where Europeans dominated, members of various Indian trading communities occupied a crucial position in Bombay’s commercial world. Foremost among these groups were the Parsis, who were considered pioneers of the cotton industry and enjoyed good relations with the British. The other communities who were present in Bombay and were active in various lines of trade were the Arabs, Banias, Bhatias, Bohras, Khojas, Jains and Memons.1 While the majority of the members of these communities were small traders, the involvement in the China trade had enabled the transformation of some of them to big capitalists.By the mid-nineteenth century, these capitalists started investing in cotton mills, facilitating the development of a vibrant cotton industry in Bombay. Several of them had also prospered due to obtaining military and government contracts, which allowed them to move to different sectors. The existing scholarship on business communities such as Parsis and Marwaris and business groups such as the Tatas, Wadias, Birlas, Bajajes and Godrejes identifies them closely with the internal economy of colonial India. On the other hand, the Gujarati Muslim business communities of Khojas, Bohras and Memons, along with Sindhis and Chettiars, have been examined as migrant groups involved heavily in external trade.2The article begins with a discussion of the Chinoy family and provides the background to their rise and importance. I use archival records and family history to narrate how beam wireless service came to India and started operations in order to demonstrate that a Khoja family firm became a source not only for introducing new technology but also for facilitating a joint venture cutting across communities. This article thus advocates an approach which goes beyond Parsi and Hindu trading groups in narrating the development and growth of capitalism in colonial India.As far as family firms are concerned, the general trend has been that Muslim groups find a place in works pertaining to Indian Ocean trade, but in the context of inland trade and industry, the focus has remained on Hindu groups.3 This article studies the introduction of the beam wireless service in India to illuminate the dynamics of a successful Khoja Ismaili family firm of the Chinoys.4 Operating the beam wireless service in India was a prestigious and crucial project and showed the confidence and reliance the government placed upon this family. A factor behind the success of this endeavour was the involvement of other prominent capitalists engineered by the Chinoys. However, they could not replicate the success of beam wireless service in their other venture, radio broadcast, which required bigger investment and a larger setup.The scholarship on radio communication and the British Empire has revolved around the role of the pioneer Guglielmo Marconi and his company, the various twists and turns in the development of the Imperial Wireless Chain,5 technological improvements and the competition for dominance among the European colonial powers.6 Much less is known of the companies that were established to construct and manage stations in the colonies and dominions to establish wireless radio communication with London. Reciprocal stations were required to complete the Imperial Wireless Chain. In the case of India, as this article recounts, a private enterprise was the most favoured option to establish and manage the wireless stations.7The credit for the introduction of the beam wireless service in India goes to two brothers, Sir Rahimtoola Chinoy (1882–1957) and Sir Sultan Chinoy (1885–1968). Their father, Meherally Chinoy (1829–1907), had started as an apprentice in the firm of Jairazbhoy Peerbhoy, a famous Khoja merchant prince, in the mid-nineteenth century. Meherally Chinoy made several trips to China and Japan, making substantial money for his employer and for himself as commission.8 He rose to become a partner in the firm and, in time, married his employer’s cousin. Though not involved in local politics, Meherally Chinoy had become a well-known name in Bombay’s trading world by the time of his death in 1907.9

Journals.Sagepub for more