by ROGELIO LUQUE-LORA

In the epilogue to the most recent edition of Nuestros años verde olivo, Roberto Ampuero meditates on what led him to write his memoirs about his time in Fidel Castro’s Cuba in the form of a novel. He concludes that only novels are able to fully capture the realities of human life, the depths of its moods and the texture of its circumstances, owing to the novelistic genre’s knowledge of the passions, cruelties and benevolence of the human soul.

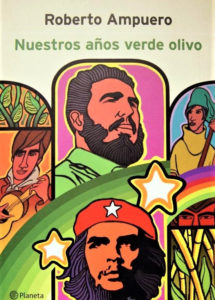

Its title, which translates as Our olive green years, alludes to the colour of the military uniform typically worn by Cuban political leaders. It is with shock that I learned that this novel has not yet been translated into English, both because of its bestseller status in its original Spanish, and because as a personal account of the political realities of Castro’s Cuba, it is irreplaceable.

This roman-à-clef (a novel relating real events, but in which the names of its characters have been changed) is the perfect companion to Jorge Edwards’ Persona non grata. Both relate the disappointment of left-leaning intellectuals upon experiencing the realities of Cuba in the 1970s. Both have been banned by the Castro brothers. Edwards’ book was published shortly after his stay on the island; its truths were therefore revealed in near-real time. In contrast, Nuestros años verde olivo first appeared in 1999. Ampuero thereby sacrificed contemporaneity but gained a half-lifetime of reflection and contextualization.

Nuestros años verde olivo commences when its author, still in his twenties, flees his native Chile in the wake of Augusto Pinochet’s 1973 coup and subsequent military regime. He goes into exile in East Germany, but soon falls in love with Margarita Cienfuegos, the daughter of Cuba’s ambassador in Moscow. At the time an enthusiastic communist and a fervent defender of the Revolution, young Ampuero travels to the Caribbean island, where he marries and settles.

Over the course of the book’s 600 pages –which, as gripping and superbly paced as they are, one reads in as few sittings as one’s other commitments allow– young Ampuero’s enthusiasm for Castro’s regime progressively dwindles. One of the effects achieved by the novelistic form is that this disenchantment is not explained in the abstract through Ampuero’s retrospective narrative voice; rather, it emerges gradually from the readers’ first-hand encounters with the author’s concrete experiences. It is therefore felt as one’s own.

The first of these disappointments is the irony of discovering that the diplomatic family into which the author marries enjoys privileges –a mansion previously owned by Fulgencio Batista’s aristocracy; access to food, clothes and jobs not available to the average Cuban citizen– that run against the grain of the ideals that they profess and enforce.

Toward Freedom for more