by ALEX COLVILLE

The Golden Rhinoceros: Histories of the African Middle Ages by Francois-Xavier Fauvelle reviewed

The main attraction in the Kenyan port of Mombasa is Fort Jesus, a vast, ochre-colored bastion overlooking the Indian Ocean. Dominating a dusty skyline of palm trees, minarets and tower blocks, it was erected during the opening cannonade of European empire. In 1505 a Portuguese armada sacked and torched Mombasa, shortly after its ‘discovery’ by Vasco da Gama. The fort stamped the city as theirs.

The coming of the Portuguese is sometimes considered the beginning of African history — a story not about Africa itself, but about bemused Europeans exploring and taming a ‘dark’ continent. And if we look at Africa before 1505, we find a world as blank as one of da Gama’s maps. This has led many to believe, as G.W.F. Hegel did in the 1830s, that Africa ‘is no historical part of the world’.

In The Golden Rhinoceros, the French historian François-Xavier Fauvelle turns the tables. He places the arrival of the Portuguese at the end of the story, as a rude interruption of what was in fact a golden age of African civilization. But even if Fort Jesus and other imperial relics linger on, little remains today to show what had made the Portuguese covet Mombasa so much in the first place. Long vanished are the palaces and mosques built entirely of coral which attracted merchants from across the Indian Ocean, swapping Persian spices, Venetian glass and Chinese porcelain for the gold and slaves which mysteriously arrived from the continent’s interior.

Mombasa was itself a dot in a network of booming coastal cities created by the Swahili, a people whose culture was a unique blend of Arabic and African that had developed over centuries. The ruins of more than 170 of their settlements have been uncovered so far, stretching from Somalia to Mozambique. The forgotten shells of some of these prosperous, powerful cities,now swamped by dense jungle, occasionally peep through the trees at the sea they once ruled.

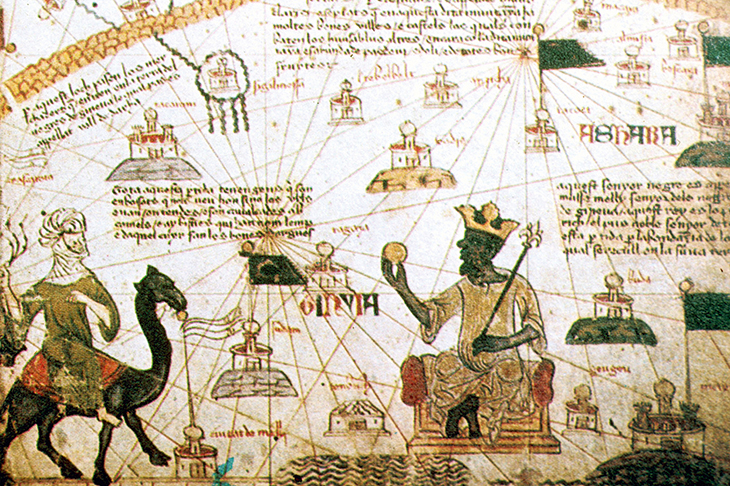

The Golden Rhinoceros is bursting with new worlds from Africa’s medieval past — a time when merchants began connecting a patchwork of ancient kingdoms, stretching from modern-day Morocco to South Africa, into wider networks of power, wealth, religion, goods and ideas. Fauvelle has created a collage of the continent from 34 different sources, each relating to trade and eloquently discussed in brief chapters. They are dots of light which, when combined, illuminate whole swathes of the dark continent, ranging from the coming of Islam in the western Sahara in the 7th century, to the 4,000 gold mines pockmarked across 14th-century Zimbabwe.

These stretches through time and space can leave the reader panting to keep up; and the absence of maps to pinpoint obscure settlements, such as Aoudaghost or Sijilmasa, only makes the uninitiated feel further lost. But perseverance is rewarded. We learn of an entire cathedral found buried beneath a sand dune in the Nubian desert, complete with vaulting and intricate murals of long-lost kings. Taghaza in northern Mali was a town made out of salt — not only through its booming trade in the mineral with sub-Saharan Africa, but because this was also the only building material to hand. A ruler of Mali set out with 2,000 ships to discover ‘the furthest limit of the Atlantic Ocean’ 180 years before Columbus. Such tales make it embarrassingly clear that Africa has a lot more to offer than safaris.

Spectator for more