by PUJA CHANGOIWALA

More than 30,000 slum residents have been forced to the ‘critically polluted’ area of Mahul as the city clears land around a water pipeline and plans a bike lane to stop residents moving back

More than 30,000 slum residents have been forced to the ‘critically polluted’ area of Mahul as the city clears land around a water pipeline and plans a bike lane to stop residents moving back

Away from the hustle and bustle of Mumbai, a sense of intense gloom pervades Mahul. The former fishing village to the east of India’s great metropolis is now home to 30,000 people who were “rehabilitated” after their slum homes were demolished to make way for infrastructure projects.

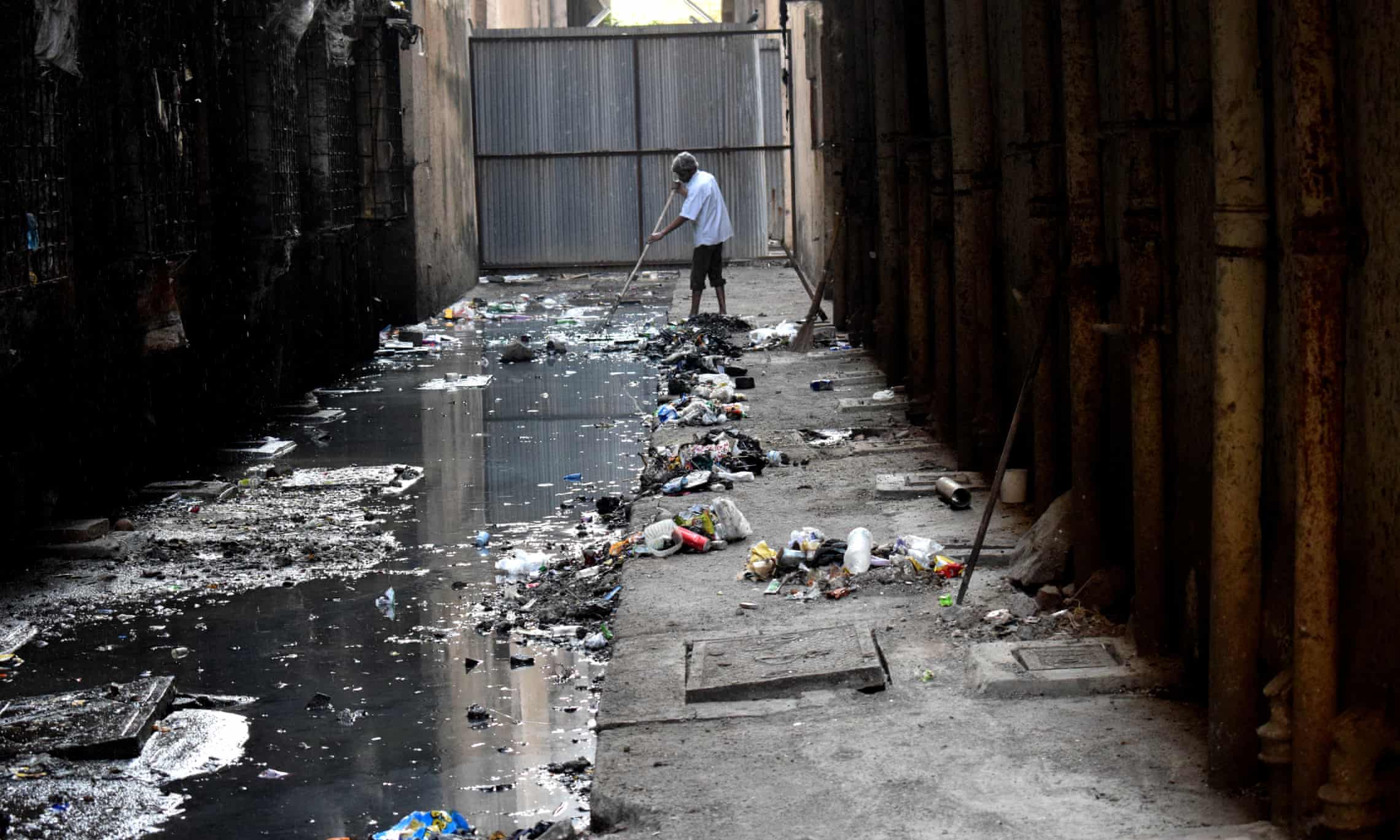

They live in 72 seven-storey buildings jammed together in the shadow of oil refineries, power stations and fertiliser plants. The air is pungent with the strong smell of chemicals. Sewage overflows into narrow streets. With the nearest government hospital seven miles away, masked patients stand in obedient lines outside homeopathy clinics, coughing.

This house has walls, a bathroom and a kitchen – but what’s the use if it’s also a gas chamber?

Kusum Gangavne

Mahul is “critically” polluted, according to India’s central pollution control board. A survey by the city’s KEM hospital found that 67.1% of the neighbourhood’s residents complained of breathlessness more than three times a month, 86.6% complained of eye irritations and 84.5% had experienced feeling a choking sensation.

“There are no schools, hospitals, medical shops or means of livelihood here,” says Anita Dhole, a 40-year-old who was relocated to Mahul after her home was demolished when authorities cleared a secure zone around the city’s colonial-era Tansa water pipeline 12 months ago. “But there are smoke-belching chimneys – and a crematorium. It’s the government’s way of telling us that they’ve sent us here to die.”

The city’s civic authority, the Brihanmumbai Municipal Corporation (BMC), started placing people in Mahul six years ago, after the high court called for 10 metres to be cleared either side of the pipeline for health and security reasons. When the BMC started clearing illegal housing, the displaced residents quickly returned to rebuild.

Last September the authorities came up with a new plan: a $45m, 24-mile cycling and jogging track along the length of the Tansa, which runs in two sections: from Mulund in the north-east to Dharavi in the centre, and Ghatkopar in the east to Sion in the south.

The Green Wheels Along Blue Lines cycle and running track would serve a dual purpose: keep the area clear of illegal shacks by opening the space around the pipeline to the public, and provide an environmentally friendly and healthy route across the chaotic and crowded city. Work is due to start in April and be completed in two years.

The Guardian for more