by STEFANI ENGELSTEIN

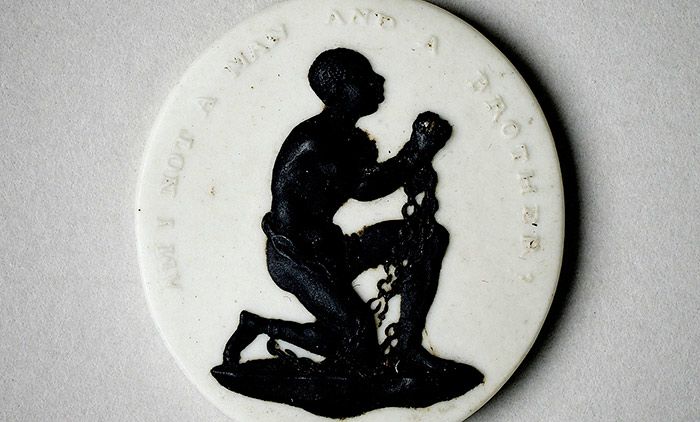

Am I not a man and brother? PHOTO/arthistory390/Flickr

Am I not a man and brother? PHOTO/arthistory390/Flickr

In 1787, the Society for the Abolition of the Slave Trade in London designed a ceramic medallion. It depicted a kneeling black man in chains, under the words ‘Am I Not a Man and a Brother?’ and was worn in the form of brooches, pendants and hair pins, as well as reproduced on larger decorative objects. The claim of brotherhood was no mere rhetorical flourish.

Shared parentage, or shared ancestry, undergirds the concept of brotherhood. But at the time, the theory of multiple human origins – polygenesis – was gaining ground. Indeed, the idea that humans descended from separate original pairs in different parts of the globe would become the dominant scientific theory in the first half of the 19th century, and remain so until the rise of evolutionary theory late in the century. The medallion, by contrast, took a stand for shared human heritage. Both polygenists and monogenists contributed to the growing acceptance of the new European theories of race that classified humans into distinct hereditary groups. Moreover, in a broader sense, both participated in a new way of thinking about classification, namely they used genealogical concepts to organise knowledge and create categories. Where did this genealogical method come from?

Race theory was far from the only new field dependent on a genealogical structure. The genealogical method – called the comparative method at the time – emerged from the new significance granted to history in the late-18th century. To take living organisms as an example, the Swedish botanist Carl Linnaeus’s classification schema in the mid-18th century used similarities in anatomy and physiology to group organisms into nested categories he designed, from the species to the kingdom. The system brought order to a chaotic profusion of organisms, but its objects were envisioned as static. While the boundaries around species were assumed to be God-given and hence present in nature, the higher levels of classification were viewed as a matter of human convenience. Even while building on Linnaean nomenclature and classifications a century later, Charles Darwin turned their assumptions on their head. He declared the boundaries around species conventional and a matter of human convenience, while the similarities by which species could be grouped together were present in nature, springing from a reproductive history of descent from a common ancestor. This thought inspired his famous 1837 drawing of a branching evolutionary tree with the enigmatic caption ‘I think’.

Aeon for more