by NIKHIL MANDALAPARTHY

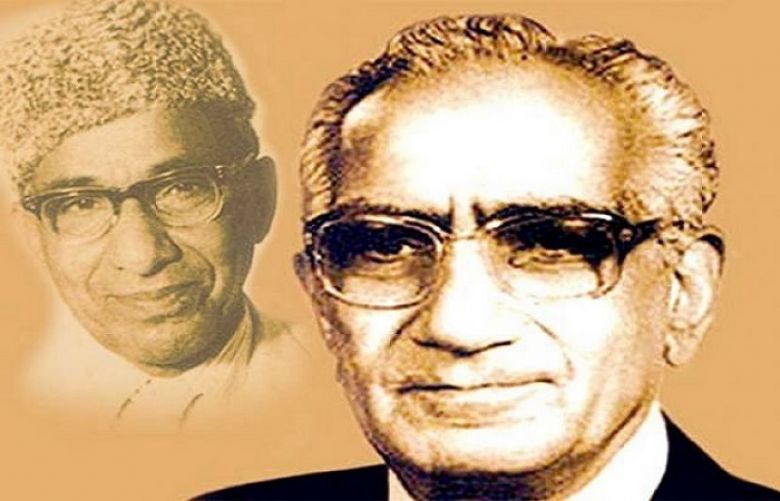

Poet Hafeez Jalandhri PHOTO/Sach TV

Poet Hafeez Jalandhri PHOTO/Sach TV

This year, Pakistan’s 70th Independence anniversary and Janmashtami (the Hindu festival celebrating Krishna’s birth) fell on the same day: August 14th. With that coincidence in mind, I want to share a very unique Urdu poem: Krishn Kanhaiya.

This nazm is by Hafeez Jalandhari, the Urdu poet most well-known for composing the lyrics to Pakistan’s national anthem, the Qaumi Taranah. Born in the Punjabi city of Jalandhar (now in India), he moved to Lahore following India and Pakistan’s independence and Partition in 1947.

As its title suggests, Krishn Kanhaiya is a poem about the Hindu god Krishna. Today, the mere idea of a Muslim poet writing about a Hindu deity raises all sorts of emotions among different groups in South Asia: surprise, joy, curiosity, suspicion, anger.

However, there is much more depth to Krishn Kanhaiya than meets the eye. This is no ordinary devotional poem. Jalandhari, ever a politically-minded thinker and writer, draws upon the mythology and persona of Krishna in order to produce a poem that is simultaneously devotional and political in nature.

It is, in fact, a call to liberate India from British colonial rule. Moreover, this poem, especially when examined in comparison with Jalandhari’s more famous work, the Qaumi Taranah, can tell us a great deal about the cultural politics of South Asia in the 20th century and today.

Setting the scene

Let’s begin with a close reading of Krishn Kanhaiya.

In the very first line of the poem, Jalandhari addresses his readers as onlookers (dekhne w?lo). Although this may seem trivial, I believe there is a deeper significance to this choice of words. Urdu poetry is usually meant to be heard, not read silently. One popular type of poetry, the ghazal, is sung, while nazms (of which Krishn Kanhaiya is one) are usually recited. Yet, Jalandhari chooses dekhne w?lo, “those who look,” to characterise the consumer of this poem.

Could Jalandhari’s choice of words be referring to the importance Hinduism gives to seeing God? I don’t think it would be inaccurate to describe Hinduism as a religion which, among the fives senses, gives primacy to sight as a way of connecting to the Divine.

The central act of devotion when one goes to a Hindu temple is darshan: gazing upon the decorated image of the deity. And, of course, the incredibly intricate and symbolic iconography of Hindu gods and goddesses suggests the importance of saguna brahman, God With a Form.

By addressing the readers of the poem as “onlookers” instead of “listeners” or “readers,” Jalandhari might be encouraging them to engage in an act of darshan in their mind. As they read or hear the poem, he encourages them to also visualise Krishna in their minds.

Dawn for more