by DON BARRETT

IMAGE/Wikipedia

IMAGE/Wikipedia

“Thus, the general theory of relativity as a logical edifice has finally been completed”—Albert Einstein, November 25, 1915

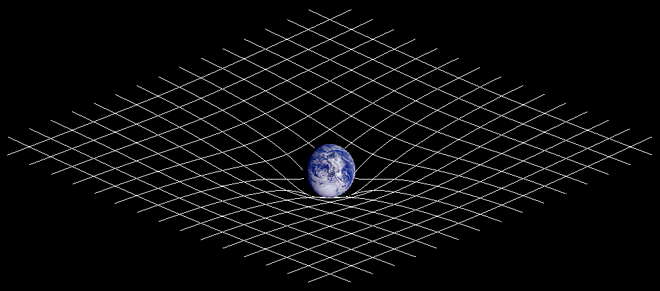

These words were spoken by Albert Einstein one hundred years ago, concluding a series of four lectures at the Prussian Academy of Sciences in Berlin on a new theory of universal gravitation, extending and amending the work Isaac Newton published 228 years earlier. In the accompanying paper, Die Feldgleichungen der Gravitation (The Field Equations of Gravitation), Einstein published for the first time the final and correct equations for what would come to be known as the general theory of relativity. This work, an elaboration on the special theory of relativity worked out ten years previously, remains one of the two central pillars of modern physics.

While the scientific community pursued and studied this work, the Great War raged in its second year. Rationing, hunger and international isolation were features of everyday life. Physicists such as Karl Schwarzschild were deployed on the various fronts. Two years later would see the conquest of political power by the masses under the leadership of the Bolshevik Party in Russia, redefining the political landscape for the rest of the century.

Produced in a revolutionary epoch, general relativity continues to be regarded as one of the momentous achievements of physics, yet its implications are far from exhausted. Even after the passage of a century, new insights connecting the theory and observed phenomena appear each year in the publications of thousands of physicists across the globe. It was the capstone to a century of intellectual struggle and the catalyst to a deeper understanding of the material world.

Einstein’s work did not emerge in isolation. The growth of 19th and early 20th century science was inseparable from the technical innovation driven by the engine of capitalism during the period of its rise as an economic system. The first high accuracy refracting telescope, built by Joseph Fraunhofer and installed at Tartu in 1824, was a derivative of the surveying theodolite, the essential tool for dividing up land and marking national boundaries. High accuracy clocks and sextants, necessary for quantitative astronomical measurements, were initially treated as strategic secrets of state because of their critical role in navigation. The invention of the telegraph allowed for closer and more immediate collaboration among astronomers both within their respective countries and across national borders. As these new more precise technologies emerged, questions regarding humanity’s understanding of matter could be revisited.

World Socialist web Site for more