by VINAY LAL

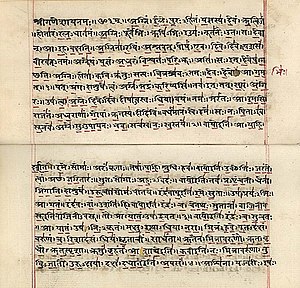

Rigveda (padapatha) manuscript in Devanagari, early 19th century. IMAGE/Wikipedia

Rigveda (padapatha) manuscript in Devanagari, early 19th century. IMAGE/Wikipedia

The Gita Press in Gorakhpur, which has printed something like half a billion copies of ‘the Hindu scriptures’, has however not printed the Rig Veda: since this text is apurusha, not made by the hand of man, it similarly ought not to be reproduced by man.

Hinduism, most of its adherents believe, is the oldest religion in the world. They are not excessively or even at all bothered by arguments that Hinduism may be an ‘invented religion’, or the view that until the 18th century, those we describe as Hindus would have known themselves as Vaishnavas, Saivites, Tantrics, Shaktos, and so on. The internet, on the other hand, is a little more than two decades old, and it has been fashioned largely in the United States. So do the startlingly old and the exceedingly young make for strange bedfellows? Or might one well argue the extreme opposite, namely that the internet and Hinduism exist in a marriage that appears to have been made in heaven?

There is but no question that Hinduism is the most apposite religion for the internet age. As is commonly known, Hinduism is a highly decentralized faith. Unlike Muslims and Christians, Hindus do not uniformly adhere to the precepts of a single book. Some Indian nationalists elevated the Bhagavad Gita as the supreme text; in more recent times, the advocates of the Ramjanmabhoomi Movement have held up Tulsidas’s Ramacaritmanas as the most venerable book of the Hindus; and yet other Hindus regard the Srimad Bhagavatam as the ‘holy book’, while others are of the view that the essence of Hinduism is crystallized in the Upanishads. The Gita Press in Gorakhpur, which has printed something like half a billion copies of ‘the Hindu scriptures’, has however not printed the Rig Veda: since this text is apurusha, not made by the hand of man, it similarly ought not to be reproduced by man. Thus the text held to be the fount of Hinduism is, unlike the Koran or the Bible, not really meant to be read at all. What would be considered a highly anomalous situation in any other religion is something with which Hindus have been comfortable for a very long time. Furthermore, Hinduism has neither a historical founder nor a Mecca; and its Shankaracharyas represent competing schools of authority.

Only Hinduism, then, can match the internet’s playfulness: the religion’s proverbial “330 million” gods and goddesses, a testimony to the intrinsically decentered and polyphonic nature of the faith, find correspondence in the world wide web’s billion points of origin, intersection, and dispersal. Hinduism has thus appeared to anticipate many of the internet’s most characteristic features, from its lack of any central regulatory authority and anarchism to its alleged intrinsic spirit of free inquiry and abhorrence of censorship. If, moreover, cyberspace is awash with images, no religion is more fecund in this respect than Hinduism. Not only do Hindus keep images of their gods and goddesses everywhere around them, but the notion of darshan, or the gaze, is central to popular Hindu religiosity.

What is equally clear is that Hinduism’s adherents, nowhere more so than in the United States, have displayed a marked tendency to turn towards various forms of digital media, and in particular the internet, to forge new forms of Hindu identity, endow Hinduism with a purportedly more coherent and monotheistic form, refashion our understanding of the history of Hinduism’s engagement with practitioners of other faiths in India, and even engage in debates on American multiculturalism. Moreover, the aspiration to create linkages across Hindu groups worldwide, embrace Hindus in remoter diasporic settings who are viewed as having been severed from the motherland, and create something of global Hindu consciousness, has a fundamental relationship to India’s ascendancy as an ‘emerging economy’ and the confidence with which its Hindu elites increasingly view the world and their prospects for prosperity and political gain.

While adherents of Hinduism are by no means singular in being predisposed towards digital media, there is nonetheless an overwhelming amount of anecdotal and circumstantial evidence to suggest that Hindus have been particularly conscientious, if not innovative and aggressive, in mobilizing members of the perceived Hindu community through the internet. The rise of Hindu militancy in India since the late 1980s, signaled by the term Hindutva, had its counterpart in the creation of new Hindutva histories on the internet. The internet was but a few years old when the Global Hindu Electronic Network (GHEN), an exhaustive site on Hinduism and its enemies, was put up by an enterprising Indian American student in the US as a point of entry into ‘the Hindu Universe’. Some of the other manifestations of viewing history as the terrain on which new and more robust conceptions of Hindu identity were to be shaped can be seen in the creation of the virtual Hindu Holocaust Memorial Museum, dedicated to advancing the argument that the holocaust against Hindus in India over a thousand years is without comparison, and in the manner in which aggrieved Hindu parents in the US waged a determined struggle, largely over the internet, on the question of the representation of Hinduism and the ancient Indian past in history textbooks intended for middle school students in California.

In some respects, however, we are on wholly uncharted territory in thinking of the future of Hinduism in cyberspace. A good illustration of some of the difficulties that might creep in, especially from the viewpoint of a devout believer, is furnished by the phenomenon that is described as online puja. The altar, or alcove where the deities are housed, in the Hindu home is kept clean. Now suppose that a person wishes to perform online puja on his computer screen. What if that same computer screen had been used fifteen minutes earlier to watch pornography? Can one ‘clean’ the computer, and erase all traces of one’s activity, by emptying the cache, resetting the browser, junking one’s files, and then deleting the trash?

In recent years, advocates of Hindutva, online and offline, have been staunch supporters of the view that Israel, India, and the United States are three democracies that are besieged by the soldiers of Islam. The website, HinduUnity.org, describes Hindus and Jews as natural allies in the allegedly global struggle against Islam. Digital media technologies have thus created new interfaces for articulations of rights, grievances, and interests in a world where rules of civic engagement on the internet are still under negotiation. Just how far internet Hinduism will proceed in helping us understand changing protocols of citizenship in a transnational world remains to be seen.

Vinay Lal’s blog is Lal Salaam