by ANDREW ANTHONY

This imaginative attempt to reconfigure humanity’s roots contends that early people were free to shape their own lives

In the wake of bestselling blockbusters such as Jared Diamond’s Collapse and Yuval Noah Harari’s Sapiens, that backwater of history – prehistory – has been infused by a surge of popular interest. It’s also proved an area of fertile promise for those who find the established narratives of modernity either constricting or based on false premises or both.

The last point is particularly relevant for the egalitarian-minded. After the catastrophic failure of the Soviet experiment, there were few places left to turn in support of the belief that humanity is at heart cooperative rather than competitive. The notable exception was the pre-agricultural era, those tens of thousands of years in which humans were thought to live in a state of… well, what exactly?

Since the Enlightenment, there have been two conflicting visions of humanity stripped of its civilised trappings. On the one hand, there is Hobbes’s notion of us as predisposed to violence – waging war against each other in a “nasty, brutish and short” existence. On the other, Rousseau’s idyll of prelapsarian innocence, in which humanity led a life of Edenic bliss before being destroyed by the corruptions of society.

Both these understandings of humanity’s roots are manifestly wrong, contend the late anthropologist David Graeber and his co-author, the archaeologist David Wengrow in their new and richly provocative book, The Dawn of Everything: A New History of Humanity. As the title suggests, this is a boldly ambitious work that seems intent to attack received wisdoms and myths on almost every one of its nearly 700 absorbing pages.

Of course, few modern scholars accept either Hobbes’s bleak caricature or Rousseau’s romantic musings. Nonetheless, Graeber and Wengrow argue, these antithetical conceptions of human nature feed into the consensus that has been popularised by figures such as Diamond and Harari.

That is to say that for most of human history our ancestors lived an egalitarian and leisure-filled life in small bands of hunter-gatherers. Then, as Diamond put it, we made the “worst mistake in human history”, which was to increase population numbers through agricultural production. This, so the story goes, led to hierarchies, subordination, wars, disease, famines and just about every other social ill – thus did we plunge from Rousseau’s heaven into Hobbes’s hell.

According to Graeber and Wengrow’s reading of up-to-date archeological and anthropological research, that story, too, is nonsense. Humanity was not restricted to small bands of hunter-gatherers, agriculture did not lead inexorably to hierarchies and conflicts and there was not one mode of social organisation that prevailed, at least until thousands of years after the introduction of agriculture.

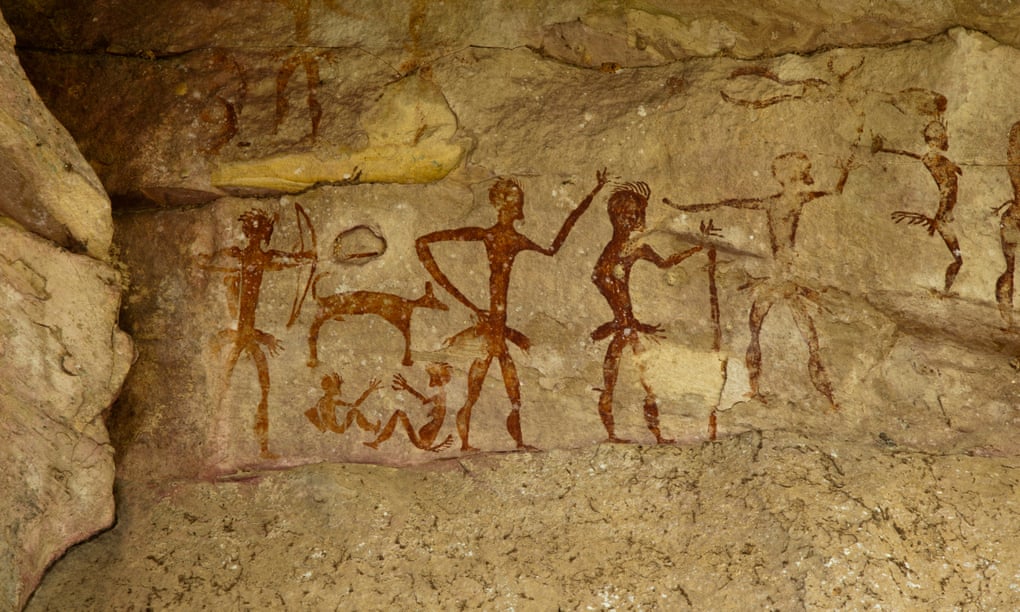

On the contrary, they maintain, prehistory was a time of diverse social experimentation, in which people lived in a variety of settings, from small travelling bands to large (perhaps seasonally occupied) cities and were wont to change their social identities depending on the time of year.

The strength of the book is the manner in which it asks us to rethink our assumptions

The author of Debt: The First 5,000 Years and Bullshit Jobs, Graeber, it’s worth bearing in mind, was a committed anarchist who was instrumental in setting up the Occupy Wall Street protest. Another factor that bears consideration is that both archaeology and anthropology are disciplines that are notoriously vulnerable to subjective interpretation.

Such “distant times can become a vast canvas for the working out of our collective fantasies”, the authors caution, but then do not entirely heed their own warning. While readily acknowledging the limitations of verifiable evidence, they nonetheless engage in creative speculation, albeit with a host of covering “most likelys”.

The Guardian for more