by JASON MILLER

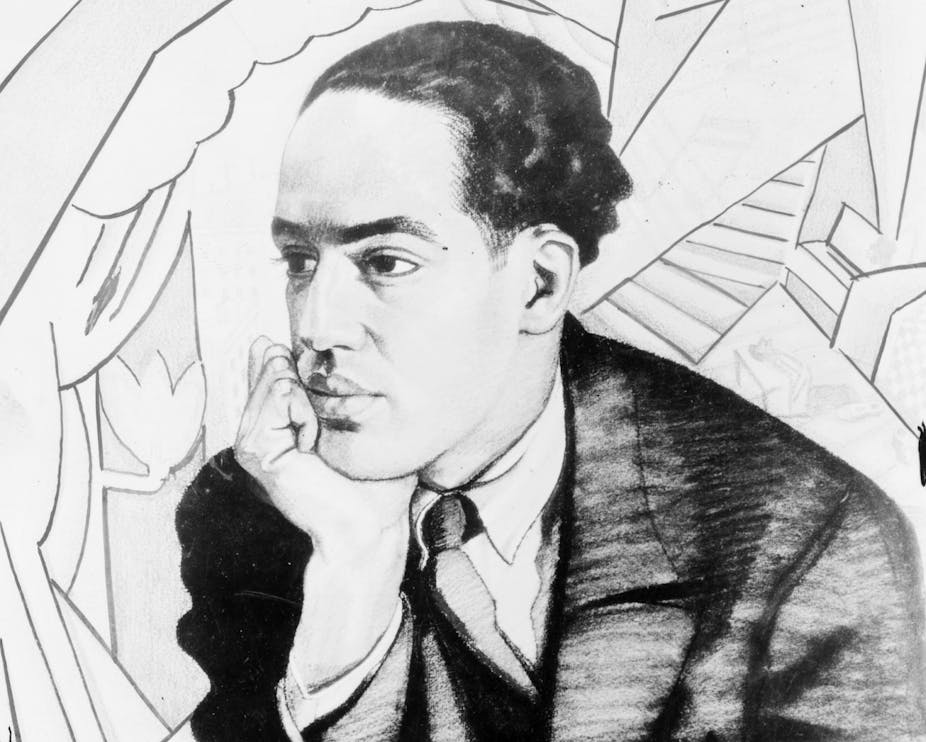

A leading figure of the Harlem Renaissance, the inspiration behind Lorraine Hansberry’s play “A Raisin in the Sun” and an uncompromising voice for social justice, Langston Hughes is heralded as one of America’s greatest poets.

It wasn’t always this way. During his career, Hughes was routinely harassed by his own government. And the nation’s literati, balking at his subversive politics, tended to overlook his work.

But the opposite was true abroad, in places like France, Nigeria and Cuba, where Hughes had legions of devoted readers who were some of the first to recognize the promise and power of the poet’s words. In my new book, “Langston Hughes: Critical Lives,” I trace Hughes’ budding international stardom, and how it clashed with the hostility he faced back home.

Building a fan base

Growing up in America, Hughes had experienced racism firsthand. As he matured as poet and writer, he started looking beyond America’s borders, curious to learn more about how racism impacted different cultures.

Between 1924 and his death in 1967, Hughes made trips to places as varied as Italy, Russia, England, Nigeria and Ghana.

During a visit to Cuba in 1930, Hughes met a young Cuban poet named Nicolás Guillén. Hughes had already successfully written dozens of poems inspired by the 12-bar structures, cadences, rhymes and subject matter of blues music. Over the course of several late-night dinners at Lolita’s restaurant in Havana, Hughes encouraged Guillén to do the same with his home country’s music.

Within days of Hughes’ departure, Guillén started writing poems making use of Cuba’s “son tradition,” a form of popular dance music. This was a key moment in the development of an artist who would go on to become Cuba’s national poet.

Conversation for more