by ERIC J. WEINER

There are two ways to be fooled. One is to believe what isn’t true; the other is to refuse to believe what is true. – Soren Kierkegaard

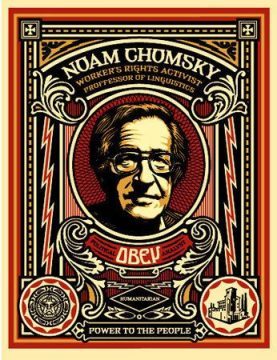

A lot has changed since 1967, the year Noam Chomsky published “The Responsibility of Intellectuals.” His essay threw damning shade at the intelligentsia—particularly those in the social and political sciences—as well as those that supported what he called the “cult of expertise,” an ideological formation of professors, philosophers, scientists, military strategists, economists, technocrats, and foreign policy wonks, some of who believed the general public was ill-equipped (i.e., too stupid) to make decisions about the Vietnam war without experts to make it for them. For others in this cult, the public represented a real threat to established power and its operations in Vietnam, not because they were too stupid to understand foreign policy, but because they would understand it all too well. They had a sense that the public, if they learned the facts, wouldn’t support their foreign policy. Of course, in retrospect, we know that this is exactly what happened. Once the facts of the operation leaked out or were exposed by Chomsky and others like him, the majority of people disagreed with the “experts.” Soon there were new experts to provide rationalizations for why and how the old experts got it wrong, but not before a groundswell of popular protest and resistance turned the political tide and gave a glimpse at the power of everyday people—the “excesses of democracy”—to control the fate of the nation and the world.

Chomsky has consistently been confident that people who were not considered experts in foreign affairs were as capable if not more so to decide what was right and wrong without the expert as a guide. This is one of the things that continues to make Chomsky such a threat to the established order. He has faith in the public’s ability to think critically (i.e., reasonably, morally, and logically) about foreign affairs and other governmental actions at the local and national levels. For Chomsky, the promise of democracy begins and ends with the people. He does not have the same confidence that those in positions of power will give the public the facts so that they can make good and reasonable decisions. But this does not mean that Chomsky uncritically embraces the public simply because it is the public. He does not support, nor has he ever, the cult of willful ignorance; that is, those members of the public—experts, intellectuals or laypeople—who, as Kierkegaard wrote, “refuse to believe what is true.”

3 Quarks Daily for more