by LAURENCE BLAIR

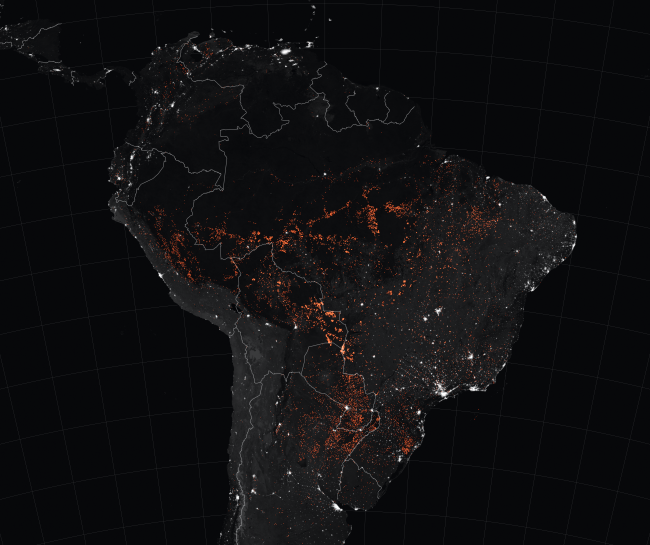

Satellite data in late August painted an apocalyptic picture of South America. Pinpricks and clusters representing the fierce forest fires engulfing the heart of the continent stretched in all directions, ignoring national borders.

Fires in the Brazilian Amazon spiked by at least 35 percent compared to the previous eight years, with blazes also arcing into the Cerrado savanna. Choking banks of smoke descended on cities in Peru’s portion of the rainforest—where fires doubled from 2018 levels—mirroring the ominous clouds that plunged São Paulo into darkness 4,000km away. Fires also spread among the Pantanal wetlands and the vast Chaco forest shared between Bolivia, Brazil, and Paraguay, setting at least 40,000 hectares of vegetation alight, and further hemming in fragile Indigenous populations like the Ayoreo and Yshir, already cornered by the advance of agroindustrial deforestation.

But perhaps the most hellish scenes are still ongoing in the Chiquitano region, a vast transitional zone of dry forest in eastern Bolivia linking the Amazon and the Chaco, and sometimes classified as lying within the Amazon biome. Here, 782,000 hectares were set aflame in August alone, adding up to over one million in 2019 so far—nearly triple the annual average rate of recent years. As in Brazil, Paraguay, and Peru, the damage to fragile vegetation and endangered wildlife will likely be untold, with local environmentalists reporting that affected areas will take centuries to recover.

Organizations like the Coordinator of Indigenous Organizations of the Amazon River Basin (COICA)—which represents the Amazon basin’s three million Indigenous people—were quick to perceive that the threat transcended territorial and political divisions. In an open letter, the group blamed the governments of Jair Bolsonaro and Evo Morales “for the disappearance of and physical, environmental, and cultural genocide in the Amazon, which through their actions and inaction worsens every day.” The respective presidents of Brazil and Bolivia, it continued, were no longer welcome in the rainforest, having repeatedly demonstrated “their racism and structural discrimination against indigenous peoples, and only looking to favour the interests of major economic groups that seek to parcel up the Amazon for agroindustrial, mining, and hydroelectric megaprojects.”

Understanding the commonalities across borders is the first step towards building strategies to help support South America’s forests and their peoples.But international coverage has been slow to look beyond the Brazilian Amazon, and adopt a similarly wide-lens, structural view. To do so is not to draw a false equivalence between Morales, the Aymara former coca leaf grower, or Bolsonaro, the nationalist ex-paratrooper. Rather it is to accept, as Uruguayan ecologist Eduardo Gudynas writes, that “we face a situation where all political ideologies seem incapable of putting out the fire,” a grim panorama in which fires are raging in all the major tropical and subtropical ecoregions of South America, “in the jungles, the dry forests, the savannas and grasslands, and even in the Pantanal.” Understanding the commonalities across borders is the first step towards building strategies to help support South America’s forests and their peoples.

Fires across the continent in the period between August and October are customary, but not natural. Farmers typically use the dry season to set less valuable, already-felled wood ablaze, clearing the space for cattle or planting. In Bolivia, this practice is known as chaqueo—a traditional, low-tech process with dubious benefit to the soil. But in both Bolivia and Brazil, many of the hundreds of thousands of individual fires were started in or spread to primary forest itself. The true damage may be even higher as blazes beneath the forest canopy are harder to detect by satellite. And in both countries, the unusually severe scale of fires corresponded to direct government encouragement. Bolsonaro’s aggressive dismantling and defunding of much of Brazil’s environmental enforcement infrastructure seems to have spurred some farmers to organize a “day of fire,” burning forest to show their willingness to advance the agricultural frontier. In Bolivia, environmentalists point to at least six presidential decrees and four new laws passed by Morales in the past six years that expand agricultural use of forests, with deforestation leaping by 200 percent since 2015. Morales also defended the fires started by smallholders—many of them poor Andean migrants and a key part of his support base ahead of elections in October—as essential for their survival, and his government has been slow to accept international assistance.

Making International Pressure Count