by DAVID LAWRENCE

Chinese scientists are leading a wave of controversial genetic experimentation

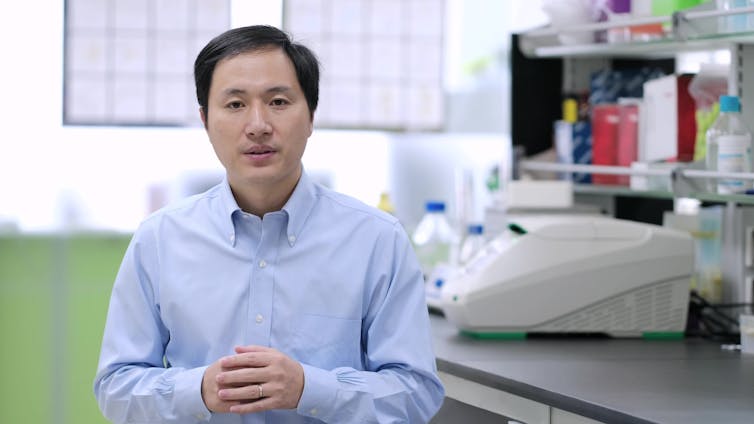

If you want to conduct groundbreaking but contentious biological research, go to China. Last year, Chinese scientist He Jiankui announced he had created the world’s first gene-edited human babies, shocking the world at a time when such practice is illegal in most leading scientific nations.

More recently, US-based researcher Juan Carlos Izpisua Belmonte revealed he had produced the world’s first human-monkey hybrid embryo in China to avoid legal issues in his adopted country.

Yet if China is fast becoming the world capital of controversial science, it is not alone in producing it. More babies produced using the “CRISPR” gene-editing technology are now planned by a scientist in Russia, where another researcher is also hoping to conduct the world’s first human head transplant. And Japan has recently lifted its own ban on human-animal hybrids.

The world is rapidly moving towards a two-tier system of cutting-edge medical research, broadly divided between countries with minimal regulation and those that refuse to allow anything but the earliest stages of this work. The consequences of this split are likely to be significant, even potentially affecting your own access to healthcare.

The births of the CRISPR babies in China led to an uproar among the scientific community, which criticized He Jiankui, and inspired calls for a halt in any CRISPR research on human embryos. In around 30 countries, gene editing of human embryos is already banned outright or at least tightly controlled. For example, in the UK only a handful of research groups have been granted a license to conduct experiments, and certainly not with any aim of bringing an embryo to term.

But in most countries, things are less clear. The Chinese establishment was quick to condemn He’s work and declare it illegal. And some commentators have made the point that, despite outside perceptions, Chinese science is far from unregulated. Yet the fact remains that He was able to conduct the work unimpeded, with evidence suggesting he may have even received state funding.

With a technology moving as quickly as CRISPR, many nations will not have had the time nor expertise to develop a comprehensive stance. As a result, it seems likely that we won’t be able to avoid a two-tier system for this kind of research. Nations with developed regulation for biotechnology will be able to adapt more quickly and easily to the latest advances and put restrictions in place. Other states will scramble to keep up, leaving scientists to proceed without having to consider the ethical or social implications of their work. And that’s assuming all governments want to restrict this kind of research, which they may not.

Asia Times for more