by ALANNA ELDER

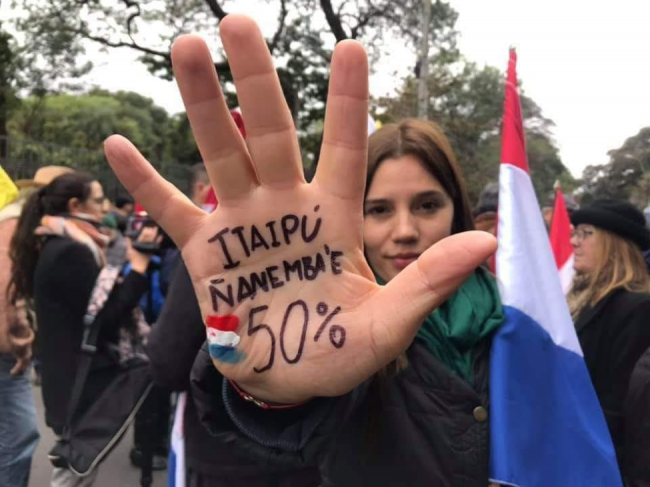

A protester with the words “Itaipu is ours” written on her hand in Guaraní demonstrates in Asunción, Paraguay, in early August. PHOTO/Itaipu ñane mba’e/Facebook)

A controversial energy deal and behind-closed-doors negotiations symbolize for many a “surrender” of Paraguayan sovereignty to Brazil and harken back to the dictatorship-era corruption that gave rise to the Itaipu dam.

The past two weeks have brought Paraguayans a political earthquake and a crowd of new household names, all connected to a bilateral energy deal signed with Brazil in May and kept under wraps until late July. Since the public learned the terms of the agreement, four top Paraguayan officials have resigned and the senate nearly impeached President Mario Abdo Benítez and Vice President Hugo Velázquez.

Although Brazil agreed to scrap the deal and restart negotiations, Abdo Benítez and Velázquez are still fielding accusations of treason and the political fallout from the deal, rooted in 50 years of tension over the world’s second-largest dam. The dam straddles the border between Brazil and Paraguay and operates under the company Itaipu Binacional, a sort of state-within-a-state run by directors from both countries. This summer’s scandal unfolded on top of a long history of inequality between Brazil and Paraguay, turning a closet shift in energy payments into a symbol of national betrayal.

By requiring Paraguay’s National Energy Administration (ANDE) to buy more expensive electricity from the dam, the deal would have raised ANDE’s costs by at least $250 million between now and 2022, according to former ANDE head Pablo Ferreira. The negotiators also capped the amount of energy ANDE could contract and threw out a clause that would have allowed ANDE to sell Paraguay’s excess electricity directly to the Brazilian market at a higher price than what it receives now. Ferreira saw the final deal on July 4, about six weeks after both ambassadors had signed it and left his job on July 24. His resignation and refusal to comply with the terms of the new agreement raised the tenor of the debate over how to share the Itaipu dam.

For many Paraguayans, the agreement represented a step backward from terms reached in 2009 and a return to the systemic corruption that gave rise to the dam during the country’s dictatorship in the late 20th century. Nearly 50 years after it was built, the dam is still central to criticisms of the former dictator Alfredo Stroessner’s Colorado Party, which controls Paraguayan politics to this day.

“The citizenry is indignant over all of the theft that Itaipu represents on a historical level,” said environmental engineer Guillermo Acucharro. He is a spokesperson for a campaign called Ñane Mbae Itaipu, which means “Itaipu is ours” in the Indigenous language of Guaraní. “The Paraguayan people know, at least for this society, Itaipu was a scam and that the government of Mario Abdo wanted to carry out a negotiation behind closed doors.”

A Dictators’ Agreement

The Itaipu Dam was born out of a border conflict between Brazil and Paraguay nearly 100 years after the devastating Triple Alliance War ended, establishing the Paraná River as the national boundary. In the mid-1960s, the military dictatorships of both countries pressed toward the Saltos del Guaíra waterfalls (Sete Quedas for Brazilians), hoping to take advantage of the water resources that plunged 375 feet. Composer Phillip Glass created a tribute to the falls and the engineering marvel that replaced them when the two governments decided to build the dam together, signing the Itaipu Treaty in 1973 and founding Itaipu Binacional the following year. Brazil’s state utility Electrobras provided the largest loan to build the dam, which began production in 1984 but was not fully completed until 1991.

One significant trade-off of the two countries’ cooperation was that Stroessner allowed Brazilians to move into the agricultural lands of eastern Paraguay. This set the conditions for the predominance of land-holding Brazilians and their descendants, who now control Paraguay’s top export, soy. In other words, the act that preceded the dam paved the way for two primary examples of how Brazil has utilized Paraguay’s natural resources—land and electricity—in some cases impeding on national sovereignty.

The 1973 treaty established that each country would own half the energy produced by Itaipu, but Paraguay consumes less than 10 percent, passing the rest to Brazil. The larger nation has always paid less than market value for that ceded electricity. Since the dam began operation in 1984, Paraguay has helped to fuel industrial development in São Paulo and elsewhere for a set compensation rate. Between 1984 and 2018, Brazil underpaid its neighbor by about $75.4 billion, according to economist Miguel Carter. Under different rules, Paraguay could have earned nearly twice its current GDP from Itaipu alone.

Even though the country has only used a fraction of the energy churned out by the dam over the years, consumers are still paying back construction debt, which makes up more than half of their electricity bills.Critics argue that on top of the lost investments their government could have made to education, health and infrastructure, Paraguayan users have been overpaying for electricity. Even though the country has only used a fraction of the energy churned out by the dam over the years, consumers are still paying back construction debt, which makes up more than half of their electricity bills. Critics like renowned Paraguayan engineer Ricardo Canese and Columbia University economist Jeffrey Sachs say Paraguay has likely already met its obligations.