by ROBERTO SIRVENT

Sometimes what passes for international law can lead to unfair outcomes, as the mandate that facilitated the creation of Israel on Palestinian land.

“The two-state solution has become dead letter.”

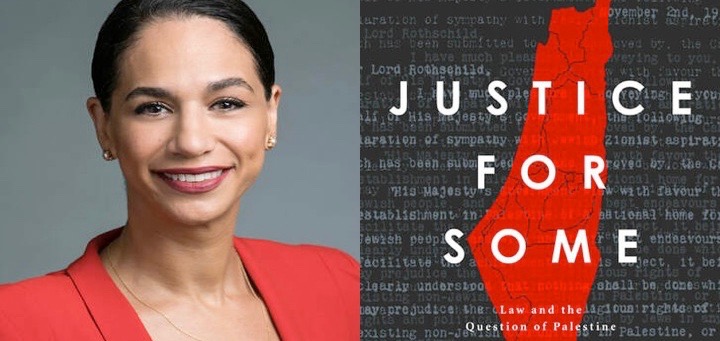

In this series, we ask acclaimed authors to answer five questions about their book. This week’s featured author is Noura Erakat. Erakat is a human rights attorney and Assistant Professor at George Mason University. Her book is Justice for Some: Law and the Question of Palestine.

Roberto Sirvent: How can your book help BAR readers understand the current political and social climate?

Noura Erakat:Justice for Some tells a different story about the Palestinian struggle for freedom by using the relationship between law and politics between 1917 and 2017 to explain a history of the present. It shows that the League of Nations Mandate for Palestine in 1922 established a legal structure of exception. The Mandate for Palestine set the administration of Palestine apart as a specialized legal regime that negated Palestinian peoplehood in order to facilitate the establishment of a Jewish national home. This legal structure has definitively shaped the Palestinian question and the subsequent book chapters demonstrate how Palestinian struggle and resistance has overcome this exception as well as how Israel has used it to facilitate its settler-colonial ambitions.

The book shows, for example, how the two-state solution has become dead letter, how Israel has managed to expand its settlement enterprise because of law rather than in spite of it, and how Israel has changed the laws of armed conflict to make the high registers of death and destruction in the Gaza Strip comprehensible within a language of law. Significantly, the book helps explain why and how the official Palestinian leadership has failed to effectively leverage the law to advance their interests. The law’s meaning and utility is contingent on the historical context, the balance of power, and the strategy of legal workers. In doing so, the book demonstrates that international law is both the site of oppression as well as resistance and, on balance, it has done more to advance Israeli interests than Palestinian ones but that this outcome was not inevitable.

What do you hope activists and community organizers will take away from reading your book?

My hope is that the book has something to offer for a range of readers. For the readers who are new to the issue, I hope that it offers a historical explanation of the Palestinian condition of unfreedom. For the readers who are experts on the Palestinian question, I hope that the book offers a new lens through which to understand the issue in ways that a book focused on the economy or racism or on gender may offer. And for the legal scholars, practitioners, and students, my hope is to offer a critical analysis about the meaning of law, how it works, and the potential and risk of its invocation on behalf of progressive causes.

For all readers, the primary take away is that the present-day status quo is not inevitable and that creating new futures is a matter of political will and mobilization. It urges a political cynicism and a strategic optimism. In the tradition of movement lawyering, the law should never supplant politics or even provide a strategic compass, but rather it should be used in the sophisticated service of a political movement.

We know readers will learn a lot from your book, but what do you hope readers will un-learn? In other words, is there a particular ideology you’re hoping to dismantle?

The book unequivocally assumes Israel’s settler-colonial nature and understands the Palestinian struggle as one for freedom. In doing so, it pushes back against a mainstream narrative that would have us believe that it the Palestinian question is a matter of conflict resolution between Israelis and Palestinians, in the best case scenario, or a national security question, in the worst case.

The Palestinian question has, in many ways, been a battle over narrative. Over 100 years, there have been several turning points in that narrative. In the mandate period, it was primarily a struggle for Palestinians to be recognized as a juridical people – like their counterparts in the Arab world – with the attendant right to self-determination. Between the establishment of Israel in 1948 and the 1967 War, it was understood as a humanitarian crisis characterized by a massive “refugee problem.” After the 1967 War, Palestinians take the helm of the Palestinian Liberation Organization (PLO) and redefine the Palestinian question as a struggle for national self-determination in the context of Third World revolt against racism, colonialism, and imperialism.

“The conflict resolution framework has been devastating to Palestinians who remain stateless and subject to Israeli dictates.”

Perhaps the most revolutionary juncture was in the early 1990s when the Cold War ended and the PLO entered into the Oslo peace process. That juncture transformed a freedom struggle into an issue of conflict resolution. It obviated the power imbalance characterizing the “Palestinian-Israel conflict” and emphasized dialogue and compromise rather than a struggle against settler-colonial domination in ways that mitigated scrutiny of Israeli policies. The international community seemed to forget that Israel was a political reality, with the 11thmost powerful military in the world, the only nuclear power in the Middle East with a robust economy in the top quartile of all states. The conflict resolution framework has been devastating to Palestinians who remain stateless and subject to Israeli dictates. The systematic wars on Gaza together with the failure of the peace process and Israel’s own declaration of its ambitions to annex the West Bank and never see a Palestinian state established has finally caused this conflict resolution framework to steadily crumble thus creating the space for the renewed understanding of the Palestinian question as a freedom struggle. I write the book within this political moment and from this perspective.

Who are the intellectual heroes that inspire your work?

Black Agenda Report for more