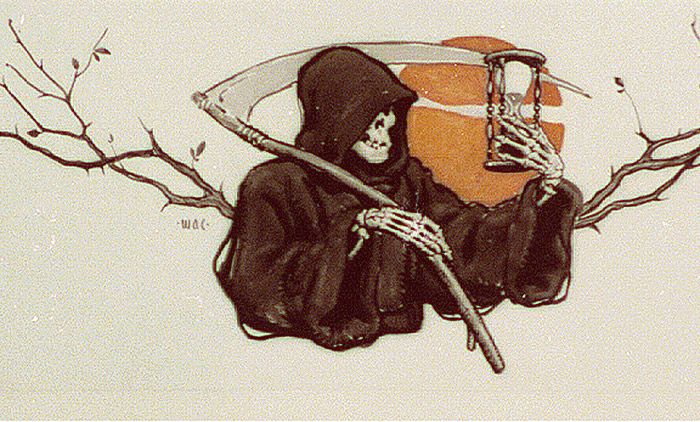

The Grim Reaper against a Red Sunset. 1905. By Walter Appleton Clark. PHOTO/Library of Congress

The Grim Reaper against a Red Sunset. 1905. By Walter Appleton Clark. Courtesy Library of Congress

As long as there has been inequality among humans, death has been seen as the great leveller. Just like the rest of us, the rich and powerful have had to accept that youth is fleeting, that strength and health soon fail, and that all possessions must be relinquished within a few decades. It’s true that the better-off have, on average, lived longer than the poor (in 2017, the least deprived 10th of the UK population had a life expectancy seven to nine years longer than the most deprived one), but this is because the poor are more exposed to life-shortening influences, such as disease and bad diet, and receive poorer healthcare, rather than because the rich can extend their lives. There has been an absolute limit on human lifespan (no one has lived more than 52 years beyond the biblical threescore and ten), and those who have approached that limit have done so thanks to luck and genetics, not riches and status. This inescapable fact has profoundly shaped our society, culture and religion, and it has helped to foster a sense of shared humanity. We might despise or envy the privileged lives of the ultrarich, but we can all empathise with their fear of death and their sadness at the loss of loved ones.

Yet this might soon change dramatically. Ageing and death are not inevitable for all living things. For example, the hydra, a tiny freshwater polyp related to jellyfish, has an astonishing capacity for self-regeneration, which amounts to ‘biological immortality’. Scientists are now beginning to understand the mechanisms involved in ageing and regeneration (one factor seems to be the role of FOXO genes, which regulate various cellular processes), and vast sums are being invested in research into slowing or reversing ageing in humans. Some anti-ageing therapies are already in clinical trial, and though we should take the predictions of life-extension enthusiasts with a pinch of salt, it is likely that within a few decades we will have the technology to extend the human lifespan significantly. There will no longer be a fixed limit on human life.

What effects will this have on society? As Linda Marsa pointed out in her Aeon essay, life extension threatens to compound existing inequalities, enabling those who can afford the latest therapies to live increasingly longer lives, hoarding resources and increasing the pressure on everyone else. If we don’t provide equitable access to anti-ageing technology, Marsa suggests, a ‘longevity gap’ will develop, bringing with it deep social tensions. Life extension will be the great unleveller.

Aeon for more