by ANDRE DAMON

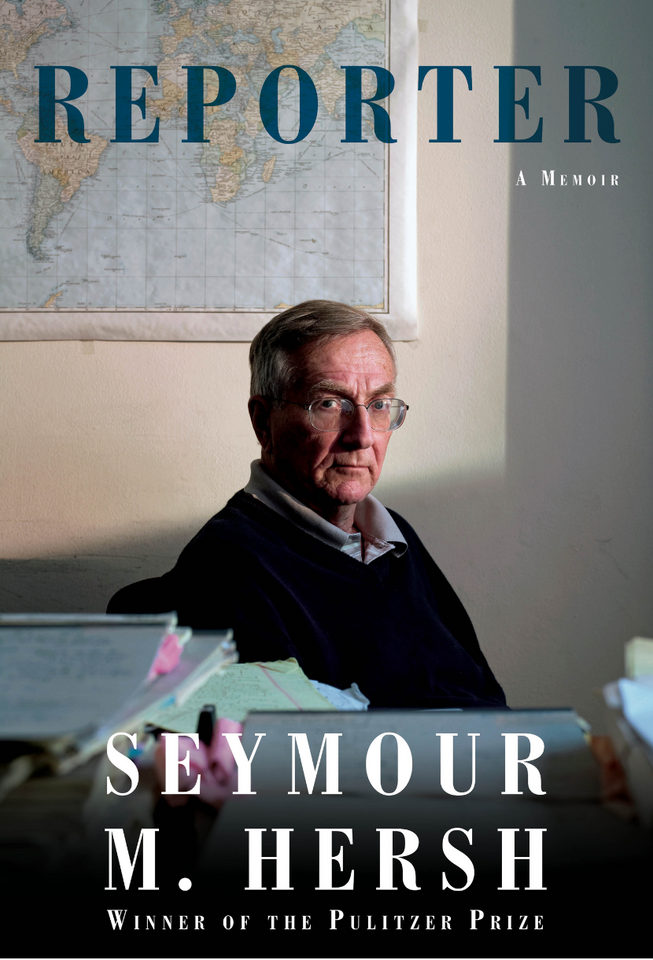

Seymour Hersh’s Reporter

Seymour Hersh’s Reporter

Seymour Hersh, the investigative journalist who played a leading role in exposing the 1968 My Lai massacre and the Bush administration’s torture of prisoners at Abu Ghraib, has published a long-awaited autobiography.

Hersh is one of the world’s most renowned investigative journalists. But despite his decades of journalistic experience, which won him numerous awards, including the Pullitzer Prize, two National Magazine Awards and five George Polk Awards, Hersh has been all but ostracized by the American press.

No prominent American, or for that matter British, newspapers or periodicals, will publish his stories. And each one of his exposures are met with vituperative denunciations, or worse—silence.

But there is nothing defensive about his memoir. Instead, Hersh has written the story of his own colorful life the same way he writes his articles. The book is a clear, gripping narrative from beginning to end, describing, first-hand, the revelation of some of the greatest crimes since the second world war.

The book’s title, Reporter, reflects its contents. The memoir is not, at first glance, a rebuttal to his contemporary critics, who call him an apologist for the Putin government because he dares question the CIA’s narrative of foreign policy; rather, he often puts the most generous interpretations on the actions of his fellow journalists.

In narrating his life, he is narrating what a reporter does, beginning with a profound skepticism about everything, most of all official statements. If the book has a leitmotif, it’s the phrase, “If your mother says she loves you, check it out,” meaning that the job of the reporter is to question and independently verify everything he hears.

The clear, but unstated, allegation of Hersh’s book is: “I am a real reporter, and my critics are not.”

Hersh phrases it more diplomatically in his preface:

“I am a survivor from the golden age of journalism,” he writes. “There were no televised panels of ‘experts’ and journalists on cable TV who began every answer to every question with the two deadliest words in the media world—’I think.’”

“The newspapers of today far too often rush into print with stories that are essentially little more than tips, or hints of something toxic or criminal. For lack of time, money, or skilled staff, we are besieged with ‘he said, she said’ stories in which the reporter is little more than a parrot. I always thought it was a newspaper’s mission to search out the truth and not merely to report on the dispute.”

“My career,” Hersh writes, “has been all about the importance of telling important and unwanted truths and making America a more knowledgeable place.”

World Socialist Web Site for more