by BRETT COLASACCO

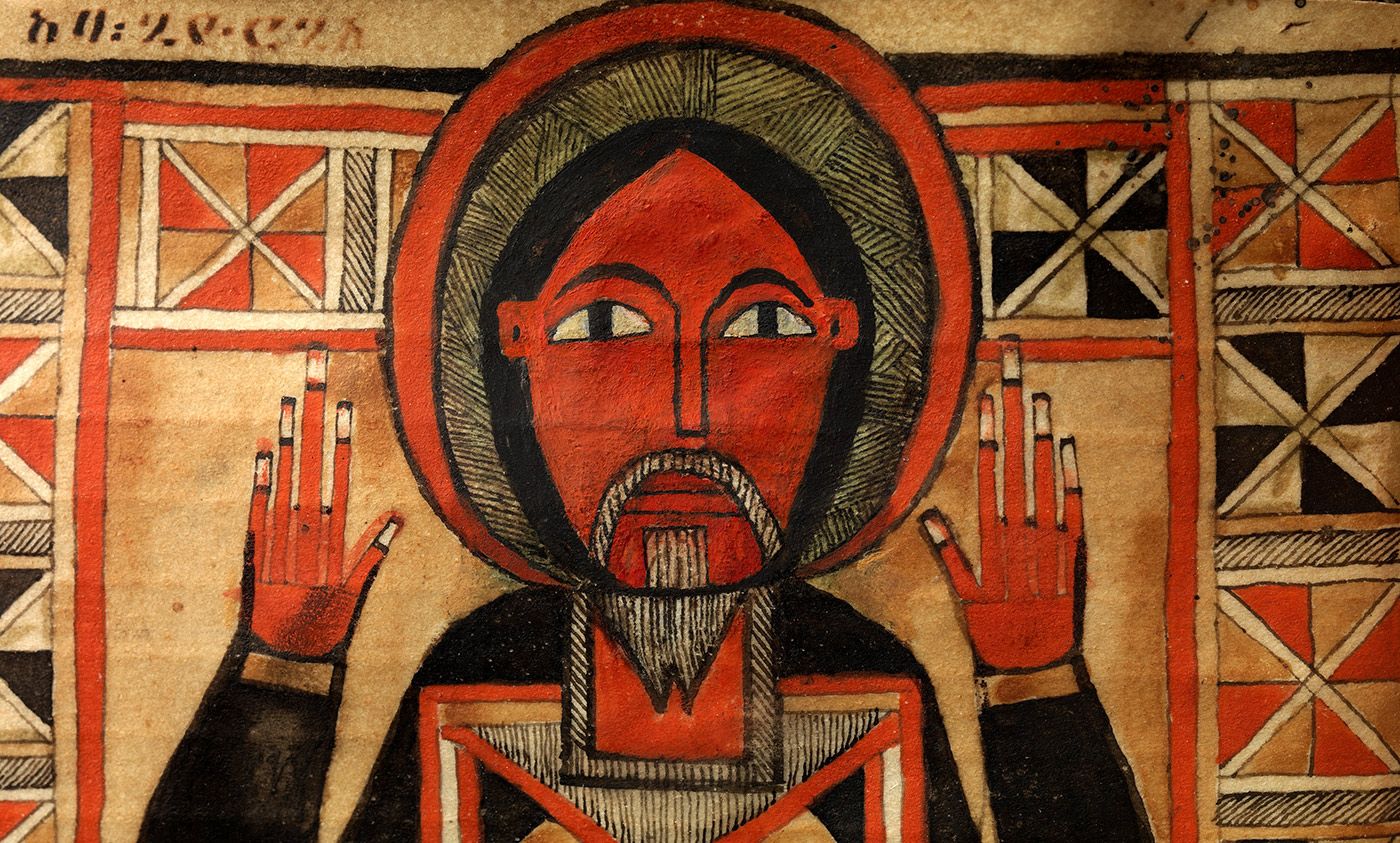

Amhara prayer book, Ethiopia, late 17th century. PHOTO/Metropolitan Museum of Art, New York

Amhara prayer book, Ethiopia, late 17th century. PHOTO/Metropolitan Museum of Art, New York

If anything seems self-evident in human culture, it’s the widespread presence of religion. People do ‘religious’ stuff all the time; a commitment to gods, myths and rituals has been present in all societies. These practices and beliefs are diverse, to be sure, from Aztec human sacrifice to Christian baptism, but they appear to share a common essence. So what could compel the late Jonathan Zittell Smith, arguably the most influential scholar of religion of the past half-century, to declare in his book Imagining Religion: From Babylon to Jonestown (1982) that ‘religion is solely the creation of the scholar’s study’, and that it has ‘no independent existence apart from the academy’?

Smith wanted to dislodge the assumption that the phenomenon of religion needs no definition. He showed that things appearing to us as religious says less about the ideas and practices themselves than it does about the framing concepts that we bring to their interpretation. Far from a universal phenomenon with a distinctive essence, the category of ‘religion’ emerges only through second-order acts of classification and comparison.

When Smith entered the field in the late 1960s, the academic study of religion was still quite young. In the United States, the discipline had been significantly shaped by the Romanian historian of religions Mircea Eliade, who, from 1957 until his death in 1986, taught at the University of Chicago Divinity School. There, Eliade trained a generation of scholars in the approach to religious studies that he had already developed in Europe.

What characterised religion, for Eliade, was ‘the sacred’ – the ultimate source of all reality. Simply put, the sacred was ‘the opposite of the profane’. Yet the sacred could ‘irrupt’ into profane existence in a number of predictable ways across archaic cultures and histories. Sky and earth deities were ubiquitous, for example; the Sun and Moon served as representations of rational power and cyclicality; certain stones were regarded as sacred; and water was seen as a source of potentiality and regeneration.

Eliade also developed the concepts of ‘sacred time’ and ‘sacred space’. According to Eliade, archaic man, or Homo religiosus, always told stories of what the gods did ‘in the beginning’. They consecrated time through repetitions of these cosmogonic myths, and dedicated sacred spaces according to their relationship to the ‘symbolism of the Centre’. This included the ‘sacred mountain’ or axis mundi – the archetypal point of intersection between the sacred and the profane – but also holy cities, palaces and temples. The exact myths, rituals and places were culturally and historically specific, of course, but Eliade saw them as examples of a universal pattern.

Aeon for more