by NATHANIRL JANOWITZ

Hugo Murrieta could draw anything. As their birthdays approached, children from the Mexican town of Coatepec would come knocking on the door of the small house he shared with his mother in the violence-riddled Gulf Coast state of Veracruz. They’d tell Murrieta their favorite cartoon characters, mostly from Disney movies, and he’d recreate them with celebratory messages to be hung at their birthday parties.

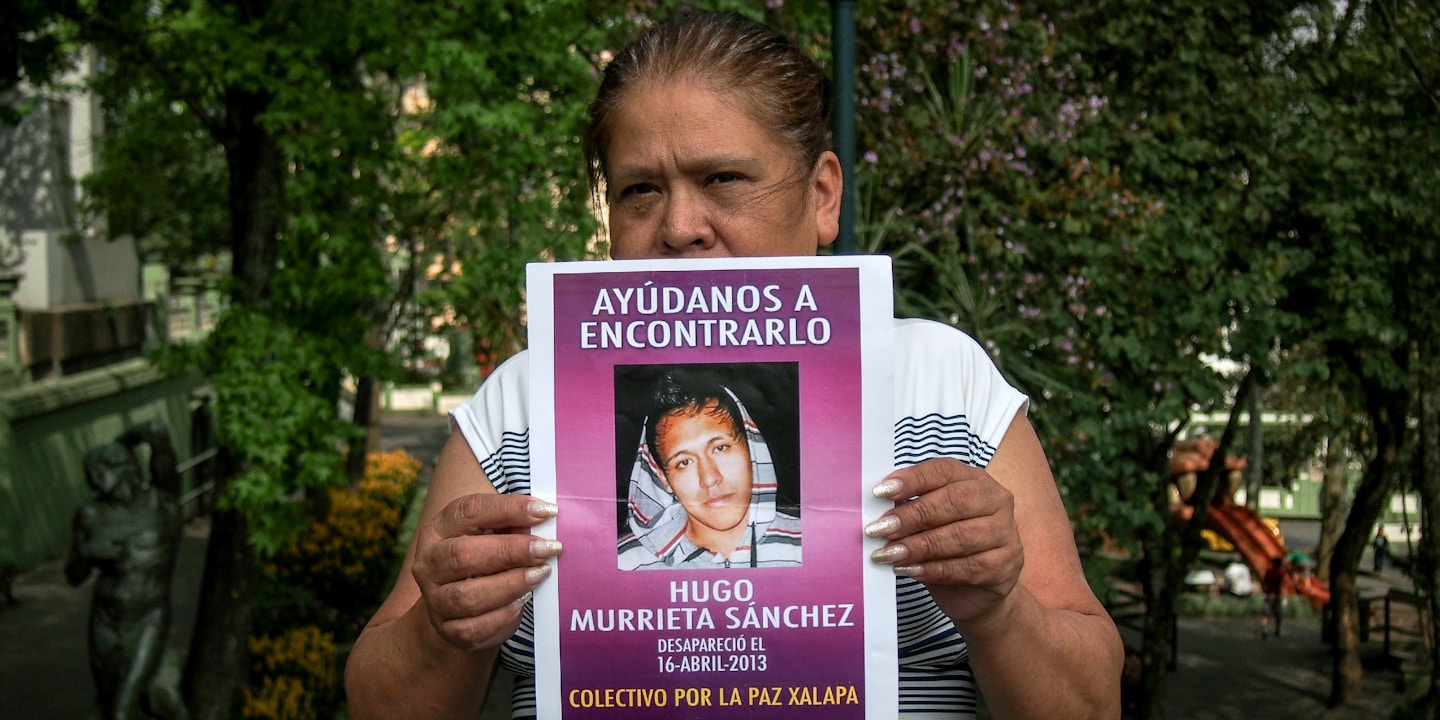

“He never charged them, just that they’d bring him the materials,” said his mother, María del Carmen. “He did it because he liked to draw.”

Murrieta’s mother was well-known in Coatepec for the delicious chiles she handmade and sold daily for decades. Each day, Murrieta, 22 years old, would help his mother by delivering them around Coatepec and nearby Xalapa, the state capital, in the taxi he occasionally drove.

Unfortunately for Murrieta, that taxi was on a police hit list, marking it for targeting by the Fuerza de Reacción, or “Reaction Force,” instated by former Veracruz Secretary of Public Security Arturo Bermúdez, an official who gave himself the code name Jaguar. On the afternoon of April 16, 2013, Murrieta was seized, beaten, and never seen again.

Nearly five years later, on February 8, 2018, a Mexican federal judge charged 31 members of the state police, including Bermúdez, for the forced disappearance of 15 people between April and October 2013. Details of Murrieta’s case emerged during the more than 13-hour arraignment hearing (although he was not among the 15 these officers were charged with disappearing). The accused, the press, and families of the disappeared listened as statements were read from two former police officers turned state witnesses and a survivor who had been held and tortured by Bermúdez’s men. The state attorney general’s office’s indictment stated that during Bermúdez’s tenure as security secretary, he had implemented an illegal, clandestine policy that included the “systemic violation of human rights” by “detecting, arresting, torturing and forcibly disappearing people supposedly linked to organized criminal groups.”

Murrieta’s mother doesn’t know why he was on a police hit list. According to her, he worked every weekend as a waiter, while during the week he delivered her chiles and operated his taxi. He never had money for art supplies; she still had to buy his clothes and shoes.

“At that time in Coatepec, they were kidnapping a lot of people, but many didn’t report it because they were afraid of the repercussions,” said del Carmen. She did call the police after Murrieta disappeared, with the hope that they’d help. They came to her home and tore apart his bedroom, flung his art supplies off the table, ripped the drawings he hung up off the wall, and found nothing illegal. She claimed that no piece of evidence has ever been presented to suggest that he had done anything wrong. She keeps a box of what remains of his art to look at when she wants to remember him.

Intercept for more